An earlier post mentioned that I’m naming my best pens — the ones I’ll pass down to my children and grandchildren — after people important in my life.

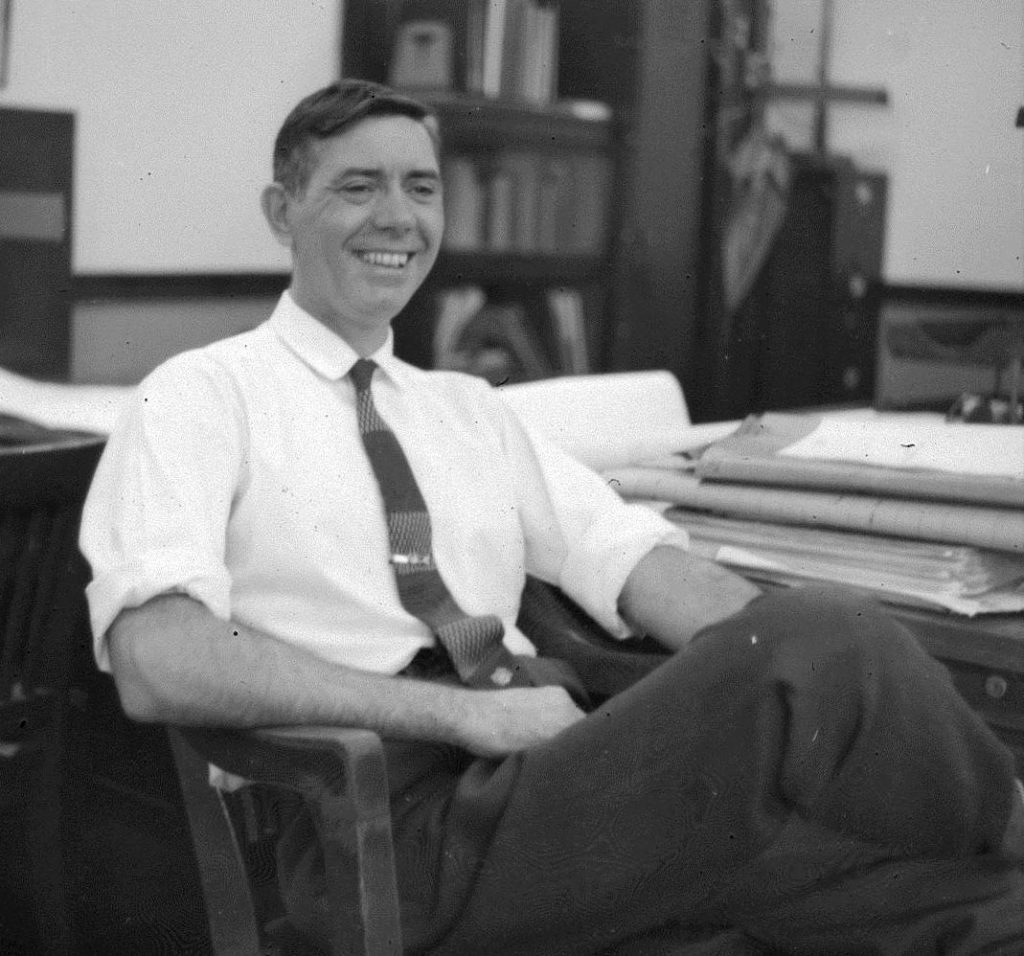

First pen up is the “Leonard,” named for my father. It’s a Montegrappa Copper Mule fountain pen, and with it’s cap embossed with 1912 — the year of the Italian company’s founding — it seems only natural that it be named after my father, who was also born in 1912.

My father, Leonard Thomas Paul Schutze (let’s call him LT), was named after his uncle Leonard Paul Schutze (let’s call him LP so we don’t get them confused). LP was LT’s father’s older brother. (Okay, so I’m confused already.)

LP, in turn, was probably named for his grandfather, Johann Leonhard Schrotzberger, picking up his middle name. LP had a rather tragic life that merits a story all its own, but that’s for another post.

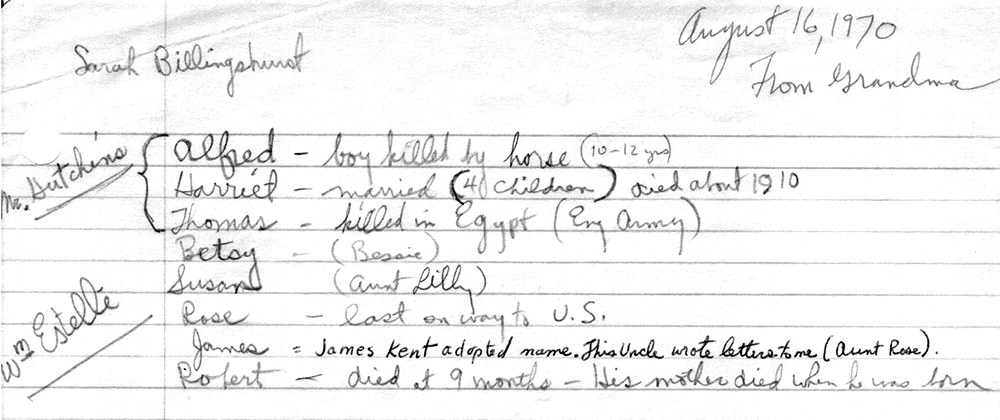

My dad’s birth certificate only shows one middle name, Thomas. I’m not sure when he was given the second middle name or if it was even official. But my speculation on the name Thomas is that it came from LT’s uncle Thomas Hutchings. Thomas was LT’s mother’s older half-brother, and he, too, merits a story of his own. He died about a year-and-a-half before my dad’s birth, and was a hero to LT’s mom, so I’m quite sure that’s where the middle name came from.

Parenthetically, my middle name is Thomas, as is my oldest son’s and my grandson’s. I’m definitely going to have to do a post on Thomas Hutchings in the future.

So, what about the pen? I bought it in 2016 and use it every day for journaling. It’s a metal pen, copper obviously, and has more weight than most fountain pens, but it’s well balanced in the hand and extremely comfortable to write with.

Being copper, the pen develops a patina over time, turning a dull brown. It can be polished to bring back the original brilliance, but that’s a bit more work than I’m willing to do, and it has a nice rustic look when left to age naturally.

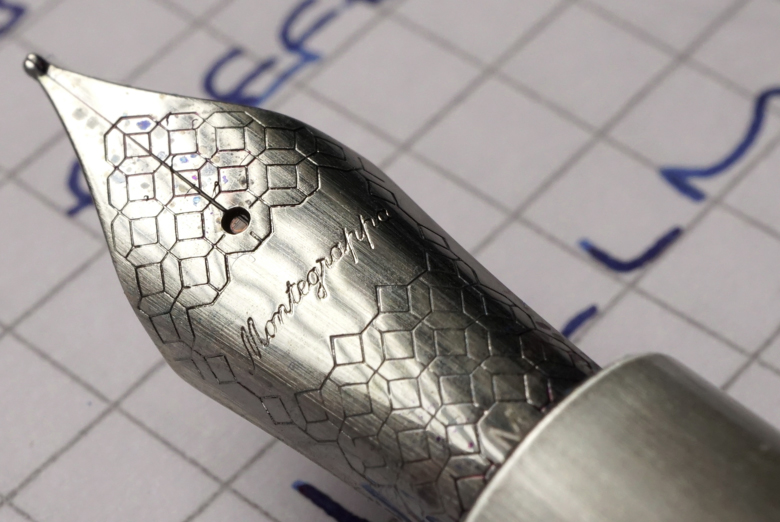

The nib is steel, with an attractive crosshatch design. It writes with a good deal of scratchiness, rather like writing with a pencil. The brushed steel grip doesn’t slip in the fingers, and the nib’s fine tip delivers a clean line, something Leonard, a draftsman and engineer, would have appreciated.

The ink delivery system is either an ink cartridge or converter. I use the converter because I prefer bottled inks. The pen is currently filled with Pelikan’s 4001 Brilliant Brown whose color compliments that of the pen. I originally tried Diamine Ancient Copper ink, but the pen writes rather dryly, and the Diamine didn’t flow well enough.

Naming the pen Leonard provides a reminder of my dad every time I pick it up. If he were still alive, I would give him the pen as a gift, and I think he would have enjoyed using it. The next best thing will be passing it down to my son. My hope, of course, is that every time he picks it up he’ll be reminded of his grandfather Leonard Thomas.