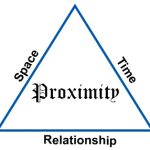

The Oxford English Dictionary defines proximity as “nearness in space, time, or relationship.” That’s a great definition for an important tool of genealogy.

Proximity is useful in figuring out family history in the absence of direct evidence such as lineage notes or official records. Relationships are typically established between people who are proximate in space and time. Generations ago one’s social environment would have been largely limited to a day’s travel on horseback or foot. So if a genealogist is trying to deduce or confirm relationships, i.e. build family trees, it’s helpful to establish that the people lived in the same area at the time in question.

Proximity is useful in figuring out family history in the absence of direct evidence such as lineage notes or official records. Relationships are typically established between people who are proximate in space and time. Generations ago one’s social environment would have been largely limited to a day’s travel on horseback or foot. So if a genealogist is trying to deduce or confirm relationships, i.e. build family trees, it’s helpful to establish that the people lived in the same area at the time in question.

Censuses dating as far back as the 1840s were useful in placing people in an area at a given time. City or area directories were also helpful, especially for years between censuses. And land records were good in identifying locations of farm families.

These kinds of documents helped discover relationships among our ancestors:

• They showed the rocky relationship between Leonard and Pearl Schutze in the early 1900s in the L.A. area. The couple lived separately as much as they lived together over the years. (Pearl eventually had an affair outside their marriage and committed suicide when it fell apart.)

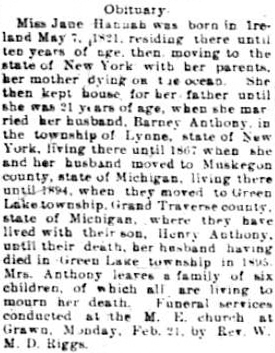

• They helped build Jane Hannah’s branch of the family tree, showing that a pair of Hannah brothers, undoubtedly her siblings, purchased a farm next door to her future husband’s family. Following the paper trail of one of those brothers showed when the family immigrated to America and from which city in Ireland.

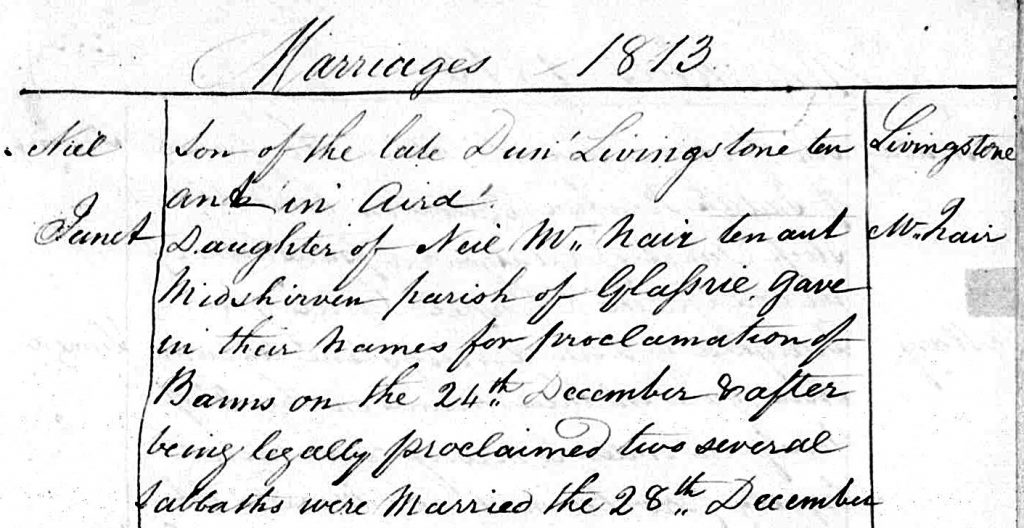

Proximity can also be determined by vital records, such as birth, death, and marriage registrations which document place.

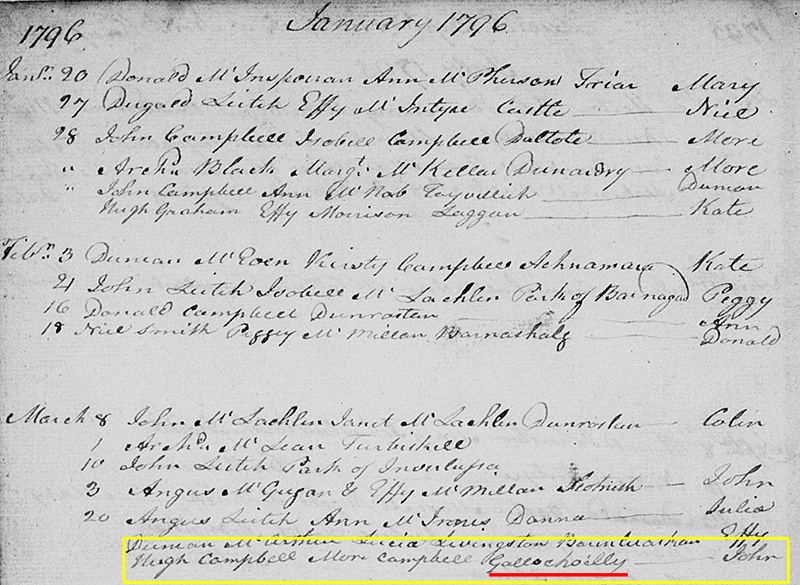

• When I was searching for the birth family of John Campbell in Scotland there was a plethora of possibilities for a man with such a common name. His gravestone determined his birth year (time). His marriage (relationship) to Isabella McLean led to the probability that his birth family lived near Isabella’s (space). Sure enough, there was a Campbell family living on the Gallochoilly farmstead adjacent to Isabella’s that gave birth to a John Campbell in the matching year. Though proximity wasn’t definitive proof, it — combined with examining all other John Campbells of the shire in that timeframe — was solid evidence that this family was by far the most likely candidate for the family tree.

Just as documents provided evidence of time and space, maps were useful in verifying spacial proximity. In the John Campbell example, it was only through old ordnance maps of Scotland that we could establish the locations of farmsteads and their proximity to each other. The same goes for 19th century township or county atlases in the United States and Canada which showed farms by family name. They documented the clustering of families in the same vicinity and showed how many marriages were spawned by the collocation of the bride and groom’s families in the area.

The concept of proximity was a terrific tool, but it admittedly may apply less to modern times than it did in the past. Generations ago families lived and worked on farms and there were limited opportunities (i.e. small local populations) to establish relationships. In the modern era people live in densely populated urban communities and work away from home so there are far more social opportunities. Add to that the increased mobility of modern transportation, mega churches drawing wide-ranging congregations, e-learning replacing fixed location schools, and the prevalence of electronic interactions, such as dating sites, and spacial proximity expands exponentially, making it potentially less useful.

In my own case, I met my wife on a blind date arranged by mutual friends. We didn’t live close by, we didn’t attend the same schools, we didn’t work in the same location, and our birth families lived a couple of hundred miles apart. A future genealogist would have a hard time trying to reconstruct our family trees using proximity as a tool. But of course in the modern era, there’s no lack of official documentation, so proximity isn’t as vital. As an aside, though, the proximity concept still applied, as it was through mutual friends (relationship) that we met, and at the time she lived with her grandmother (relationship), which placed us in adjoining counties of geographical (space) proximity.

There’s an iconic moment in the movie The Graduate when a family friend, Mr. McGuire, gives career advice to the newly minted college graduate Benjamin:

Mr. McGuire: I just want to say one word to you. Just one word.

Mr. McGuire: I just want to say one word to you. Just one word.

Benjamin: Yes, sir.

Mr. McGuire: Are you listening?

Benjamin: Yes, I am.

Mr. McGuire: Plastics.

I guess you could say that I’ve found one word that has helped me a lot in family research. Are you listening? Yes? Proximity.

sacrifice of my own. I’m sure it was his guiding spirit that steered some yokel into backing his pickup truck into the front of my automobile. I could almost hear Barney’s rheumy laugh as the grill on my car caved in and began to look like what I imagined was his gap-toothed grin. Touche, Barney. I’m not likely to forget this little visit into your past. Apparently you still have a few tricks left up the sleeve of that uniform.

sacrifice of my own. I’m sure it was his guiding spirit that steered some yokel into backing his pickup truck into the front of my automobile. I could almost hear Barney’s rheumy laugh as the grill on my car caved in and began to look like what I imagined was his gap-toothed grin. Touche, Barney. I’m not likely to forget this little visit into your past. Apparently you still have a few tricks left up the sleeve of that uniform.

And the people were great: the owner of the cherry store kept her shop open for our late arrival, and a researcher at the public library gave me tips on finding the family in the library’s on-line archives of the Traverse City newspapers.

And the people were great: the owner of the cherry store kept her shop open for our late arrival, and a researcher at the public library gave me tips on finding the family in the library’s on-line archives of the Traverse City newspapers.