It seems fitting that Transcending — a labor legacy landmark on Detroit’s riverfront — sits on the spot of one of my ancestor’s former work sites.

And the UAW-Ford National Programs Center building sits on another. Both are monuments to labor.

It’s a fortuitous coincidence that these monuments occupy the sites of my grandmother’s initial foray into the labor market of a growing industrial city. In my mind, the aptly named Transcending commemorates her, and generally speaking our family’s, move from the farm to the city, the transition from the agrarian to the industrial age.

Sarah Campbell Livingstone [later McCrie] came to Detroit with her mother and siblings in 1897, the year after her father died on the family farm near Alviston, Ontario. She was 21 years old.

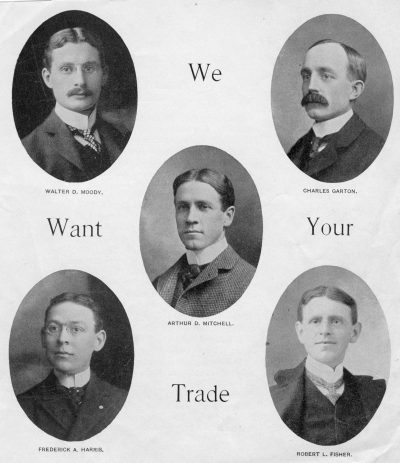

Sarah went to business school for six months and began working as a stenographer for the H. T. Bush Produce Company on Woodbridge Street in downtown Detroit. The company was on the first floor of a two-story building whose upstairs occupant was the American Eagle Tobacco Company. She earned $6.00 a week.

Four years later she doubled her earnings when she went to work as a stenographer for Mitchell, Harris & Company, a wholesale millinery two blocks away on Jefferson Avenue near Griswold Street. She worked there for about 10 years.

That area of Detroit was long ago re-purposed and is now the location of Hart Plaza, filled with monuments, fountains, footpaths, and memorials on the riverfront.

Using the 1897 Detroit street directory and Sanborn fire insurance map, as well as an 1885 map of the area, one can pinpoint the locations of her former work sites with the help of Google Earth:

• H. T. Bush Produce Company was located where the present day UAW-Ford National Programs Center (formerly the Veterans Memorial) building sits.

• Mitchell, Harris & Company was located where the Transitioning labor legacy landmark now stands.

Sarah Livingstone worked in the buildings outlined in red.

The next time I visit Detroit I’d like to make a trip to Hart Plaza and stand where she stood over a hundred years ago. Closing my eyes, I’ll think of her among an army of produce, fish, dry goods, tobacco, lumber, clothing, machinery, and millinery workers bustling among the offices, warehouses and shops of bygone Detroit. A farm girl turned urban woman, laboring to make a living for herself and family, and soon, in 1912, to marry James W. McCrie and make a family of her own.

Transitioning is a monument designed for reflection on the importance of labor. When I next visit, it will also be a place to reflect on the transience of time and on the importance of family.