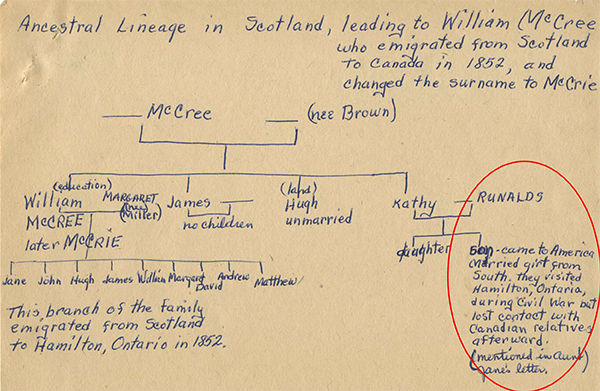

“…came to America. Married girl from South. They visited Hamilton, Ontario, during Civil War but lost contact with Canadian relatives afterward.”

This snippet written on a hand-drawn family tree aroused my attention. Who was this unnamed McCrie kin? When did he arrive in America and where did he settle?

I set out to put some flesh on this skeleton. Then I discovered a surprising twist to his story — he enlisted in a Confederate infantry regiment at the start of the American Civil War.

The Civil War has stirred considerable interest in recent months. Confederate statues and flags have fallen out of favor as symbols of Southern pride, now being viewed by many as symbols of white supremacy and slavery. Finding a Rebel in the family? That seemed like a real outlier for my family … a family that has its roots in the north.

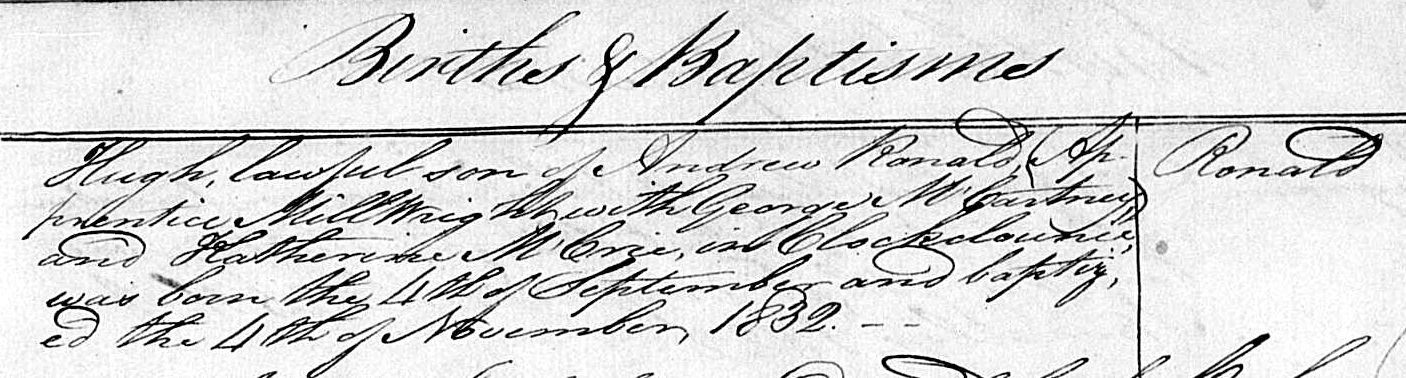

As background, this “Reb” Hugh Ronald was the first-born son of Andrew Ronald and Katherine McCrie — Kathy being the sister of my great-great grandfather William McCrie. Hugh was born in 1832 in Old Cumnock, Scotland, at a farmstead where his father apprenticed as a millwright.

When Hugh was three his family moved to Glasgow where his father practiced his trade by the River Clyde. When the family subsequently moved to Ireland in around 1840, Hugh was left in the care of his grandparents back in Old Cumnock, appearing with them in the 1841 census. Some time later his family returned to the Glasgow area, and in 1851, Hugh, age 18, showed up in the census with them working as a flesher (butcher).

In 1858 Hugh emigrated to America. It’s unknown where he first settled in his adopted country. There is only one Hugh Ronald I could find in the American 1860 census, and that was a 25-year-old Scotsman living with a Canadian-born wife and working as a clerk in Buffalo, New York. I can’t find anything to corroborate that this is our Hugh, but the country of origin, age, and occupation fit his profile. If it was him, however, it begs the question of what became of the wife and how to explain the next chapter in his life.

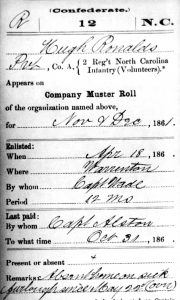

Hugh next appears in Warrenton, North Carolina, where as a salesman he enlisted for a 12-month hitch in Company F, North Carolina 12th Infantry Regiment, on April 18, 1861. North Carolina was moving in the direction of secession in early 1861, but the Confederate attack on Fort Sumpter on April 12th seems to have inspired the state to take over three U.S. forts and an arsenal. A month later the state adopted an ordinance of secession, becoming the tenth Southern state to do so.

In a time of conflict young men’s souls seem to swell with patriotic fervor and martial stirrings. Hugh—in his late twenties—may have been caught up in the frenzy. At least that’s a natural assumption when seeing that he enlisted the week after Fort Sumpter fell. The evidence is more nuanced, however.

Company rolls show that he mustered into service as a Private on May 17th, but within a week was “absent on furlough from sickness.” Subsequent muster rolls show he never returned and at the end of the year was “discharged for sickness” effective New Year’s Day 1862. Hugh may have put some of his persuasive salesman skills to work here.

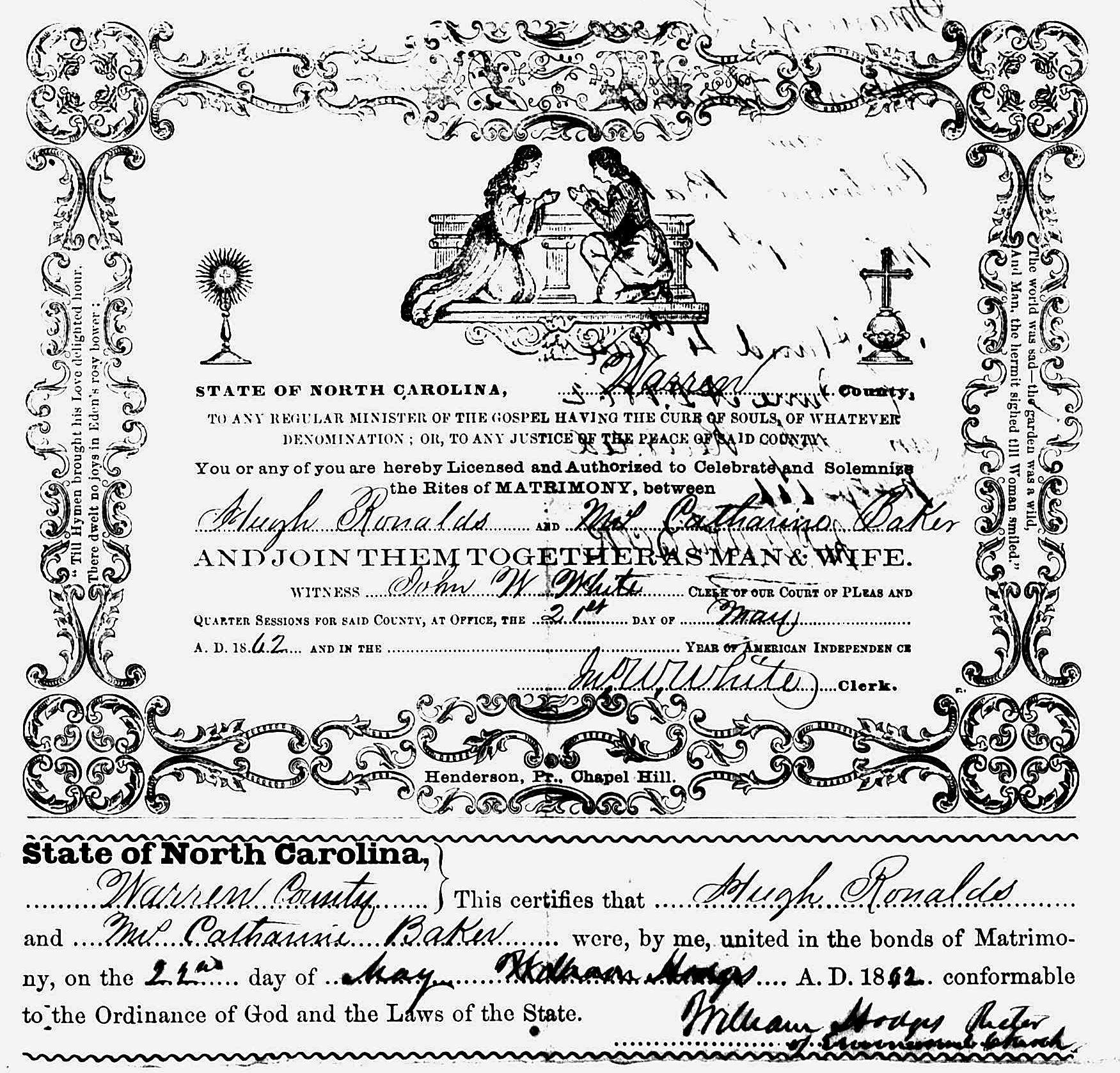

Hugh remained in the South for at least a couple of years, marrying the Carolinian native Catharine Baker in Warrenton, North Carolina — in the Piedmont region just south of Virginia — in May of 1862, when they were both 29. They had a daughter there, Kate McCrie Ronald, in October of 1863. However by the time they had their next child, Andrew, in 1866, they had moved north and were living in New York state. Considering the note on the family tree that “they visited Hamilton, Ontario, during [the] Civil War,” it’s likely they left North Carolina before the war’s conclusion in 1865.

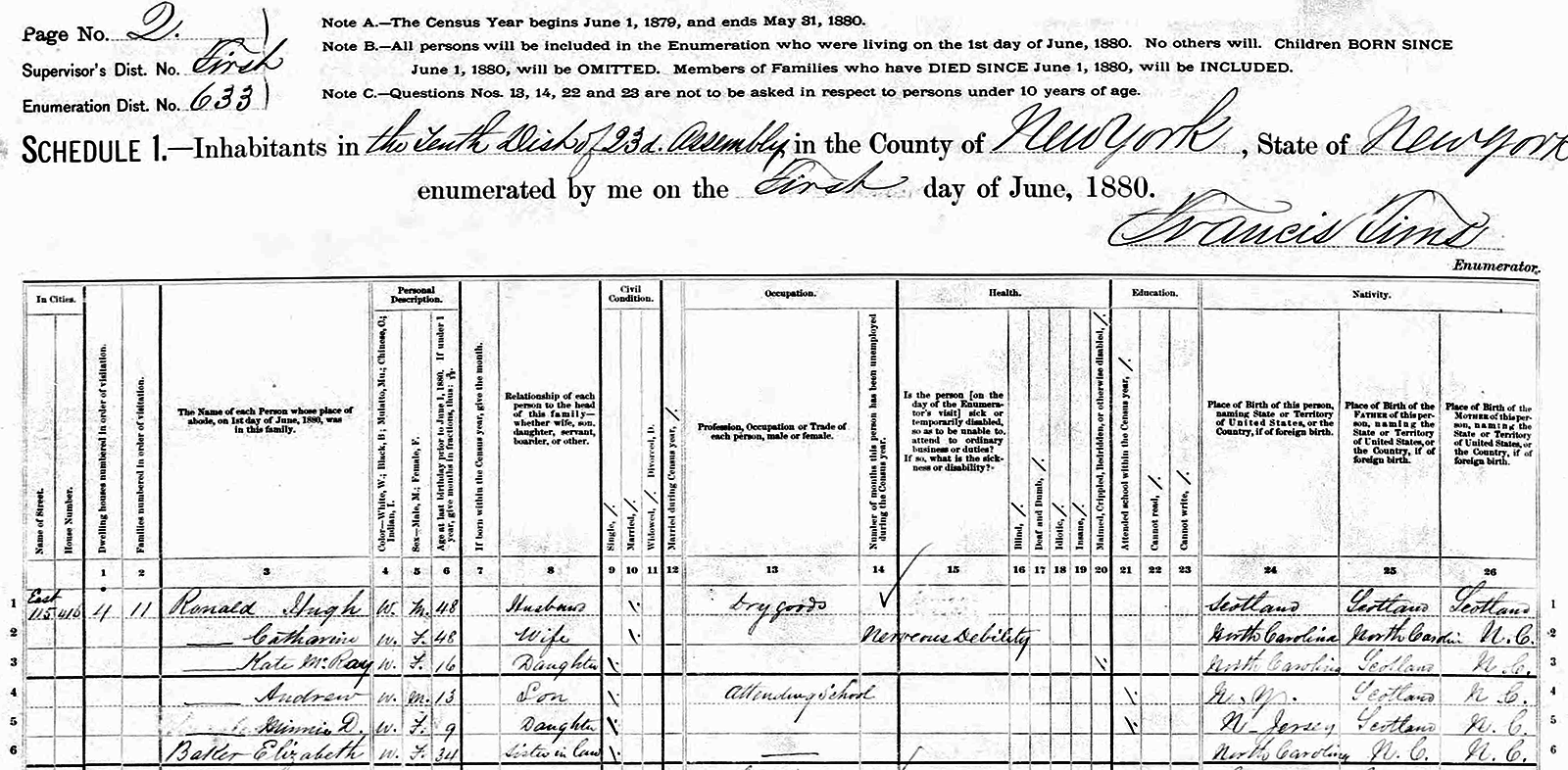

Hugh and his family, which grew to four children (although one, John, died early) lived primarily in Jersey City, New Jersey, with a two year stint across the Hudson river in East Harlem, on Manhattan. He reported his work variously as a clerk and a salesman of dry goods.

There are a couple of intriguing items in the federal censuses. In the 1880 census — when he and his family were living in New York City — his wife Catharine is noted as having “Nervous Debility.” This fell under the column “Is the person sick or temporarily disabled, so as to be unable to attend to ordinary business or duties?”

In the same census, their daughter Kate McRay [sic] Ronald, at age 16, is checked off under the column headed “maimed, crippled, bedridden, or otherwise disabled.” Kate subsequently never married, was never employed, and died at age 40.

Catharine’s younger sister was living with them, as she had in the previous census. She was probably helping to tend to the children and run the household, as the earlier census listed her as a domestic servant rather than a family member.

The 1890 census had a schedule showing “Surviving Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines, and Widows, Etc.” Although Hugh is listed, none of the columns were filled out. The federal government was only interested in Union soldiers, many of whom were eligible for pensions. The individual Southern states were responsible for their own veterans. Hugh was probably ineligible for that too. In fact, given his week’s actual time in service (probably spent in-processing), I’m surprised he self-identified as a veteran.

Hugh lived to see two children get married — at least one was a home wedding — and to enjoy two grandchildren, including his namesake Hugh. He’d been married 38 years when he passed away in 1901 at the age of 69 in Jersey City, near the piers. He left behind his widow and his daughter Kate at home. His son Andrew (with wife Nellie) and daughter Minnie (with husband Alfred Houliston) were raising children in their own homes in the city.

A son of Scotland, and a long-time resident of Jersey City, Hugh’s unlikely and short-lived spell as a soldier in the Confederate army seems an anomaly. It’s open to speculation as to the nature, or legitimacy, of the “sickness” that generated a soldier’s wages without its hardships. Equally mysterious is his presence in North Carolina during the Civil War. There are just some chapters of family histories that remain mysteries.

Hugh is one of those skeletons in the family closet — unnamed, slightly scandalous, and bare boned. Despite our best efforts to put some flesh on his remains, we’ll probably never get a full picture. But at least now we know of another McCrie family branch that immigrated to America … and hope that some day we can reestablish the contact that was lost during the Civil War.