I seem to come from a family of lovers, not fighters.

Few of my ancestors served in the military, and fewer still saw combat. In the American Civil War a Rebel family member lasted a week in the Confederate army and a Yank three months in the Union’s before they were discharged.1 In the British Army of the 19th and early 20th centuries, one of my kin was discharged for being unfit, one committed suicide, and one deserted.2

In short, my family was more likely to pass mustard around the dining room table than to pass muster in the Army.

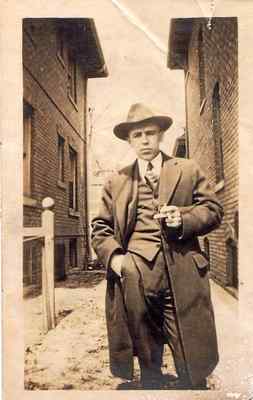

So it was with some surprise I found a picture of a World War I doughboy amongst the piles of family photographs. Who was this outlier, I wondered, and what was his story?

The soldier, Malcolm Livingstone MacKellar, turned out to be my mother’s cousin, and he served in a U.S. Army field artillery regiment in France during World War One.

Malcolm, or Mac as he was called, was born in 1892 on a farm outside of Alvinston, Ontario, the youngest of three children of Duncan and Maggie (nee Livingston) McKellar.3 Malcolm was named for his paternal grandfather, who according to a family note, was not a “church person” and used rough language.4 However the grandfather was “industrious and smart,” traits that Mac apparently inherited.

Mac had a somewhat rocky start in life. His mother died of blood poisoning before he was three — which, incidentally, was the duration of her illness, one apparently contracted during pregnancy or childbirth. His father died of uremia when Malcolm turned eight. As a consequence, in 1900 the three orphaned farm children were taken in by their maternal grandmother Sarah Livingstone who was living in Detroit with her daughters.

The grim reaper wasn’t done with Malcolm’s family, though, striking down his sister Sarah with pulmonary congestion (possibly TB) and heart disease in 1907 at the age of 16. Only two of the original five MacKellar family members were left: Malcolm and his older sister Katie. But they were surrounded by a supportive family. The 1910 census shows the 18-year-old Mac living in a household that included his sister Katie, his grandmother, four aunts, an uncle, and a cousin. The Livingston clan was a tight-knit bunch.

The Maturation of Malcolm

Mac did well in the schools he attended. He was apparently smart and sociable, evidenced by his election as president of his eighth-grade class at Amos school, and president of his senior class at Western High School. A newspaper article mentions him addressing his high school graduation in 1911.

Mac did well in the schools he attended. He was apparently smart and sociable, evidenced by his election as president of his eighth-grade class at Amos school, and president of his senior class at Western High School. A newspaper article mentions him addressing his high school graduation in 1911.

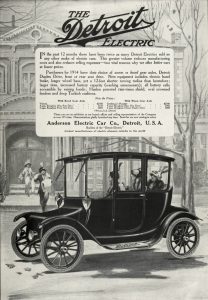

The decade after high school was a time of growing maturity for Mac and his city. Detroit became an industrial powerhouse as the emerging automobile industry set up shop there, and Mac rode the wave to become a chief clerk at the Anderson Electric Car Company, whose factory was located a few blocks from the Livingstone home. The year 1917—when he was age 25—was a particularly pivotal year for Mac: In April he applied for naturalization in his adopted country; in June he registered for the newly instituted military draft; and in October he married a 22-year-old stenographer, Edna Persinger, likely a co-worker at Anderson.5

The decade after high school was a time of growing maturity for Mac and his city. Detroit became an industrial powerhouse as the emerging automobile industry set up shop there, and Mac rode the wave to become a chief clerk at the Anderson Electric Car Company, whose factory was located a few blocks from the Livingstone home. The year 1917—when he was age 25—was a particularly pivotal year for Mac: In April he applied for naturalization in his adopted country; in June he registered for the newly instituted military draft; and in October he married a 22-year-old stenographer, Edna Persinger, likely a co-worker at Anderson.5

Lead Up to War

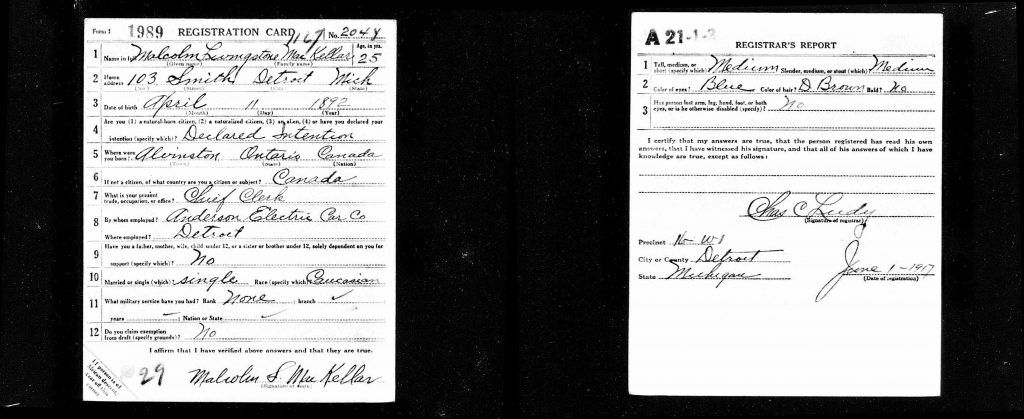

Clouds were building on the eastern horizon as Europe was embroiled in a war that began in 1914. The U.S. had remained a non-combatant heading into 1917, but declared war in April of that year as Germany ordered its U-boats to sink American supply ships heading to Britain. American conscription was authorized and Malcolm’s draft registration card showed he was in the process of becoming a citizen, was of medium height and build, had blue eyes with dark brown hair, and was working at Anderson.

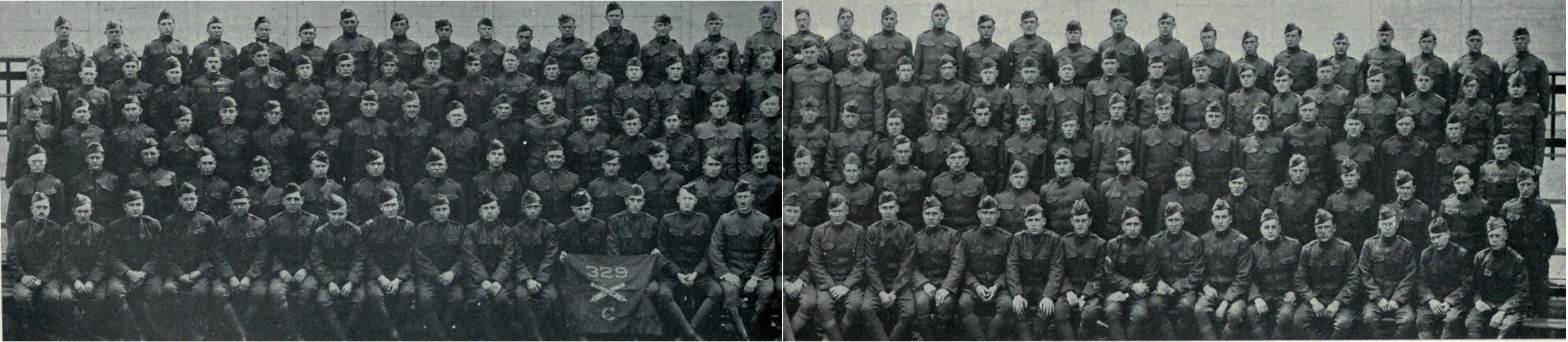

Over the next two years the Army inducted 2.7 million draftees. Mac ended up as a corporal in Battery C of the 329th Field Artillery Regiment, 160th Field Artillery Brigade, 85th Division (the National Army of Michigan and Wisconsin). The regiment was mustered in and trained at the newly constructed Camp Custer near Battle Creek, Michigan. Mac joined the unit a couple of weeks after his marriage, arriving just before Thanksgiving of 1917.

Horsin’ Around

On December 12th the battery received their horses — “164 of the wildest, head shy, hard kicking and sharp biting, four-legged animals that ever graced (or rather disgraced) the name of horse,” according to Sgt. Menzies, a chronicler of his battery. [All of the following war-time quotes and most of the photos are from the book All The Way with the Boys of the 329th Field Artillery.] The winter was snowy and cold, making the conscripts’ lives an endless cycle of “shovel snow one day, coal the next, stable police, then kitchen police, afterwards guard (oh, those terrible 22 below zero days on which to walk a post) and between times … we drilled and drilled and physical cultured and went to various specialty schools.”The battery, at a strength of about 185, had only a few more men than horses. Though many of the Detroit conscripts were more familiar with automobiles than horses, the Army found the animals were still more reliable than vehicles for traveling through deep mud and over rough terrain and they were used for pulling artillery.6

Valentine’s Day in 1918 was the first time Battery C hitched their horses up to the artillery pieces and caissons and actual drill practice began. April brought pistol practice and shortly thereafter artillery firing on the range, first with sub-caliber shells for short distance, then regulation 3-inch shells at normal distance. In early May “rumors of leaving for overseas were becoming more pronounced and drill periods were made harder and longer.”

Valentine’s Day in 1918 was the first time Battery C hitched their horses up to the artillery pieces and caissons and actual drill practice began. April brought pistol practice and shortly thereafter artillery firing on the range, first with sub-caliber shells for short distance, then regulation 3-inch shells at normal distance. In early May “rumors of leaving for overseas were becoming more pronounced and drill periods were made harder and longer.”

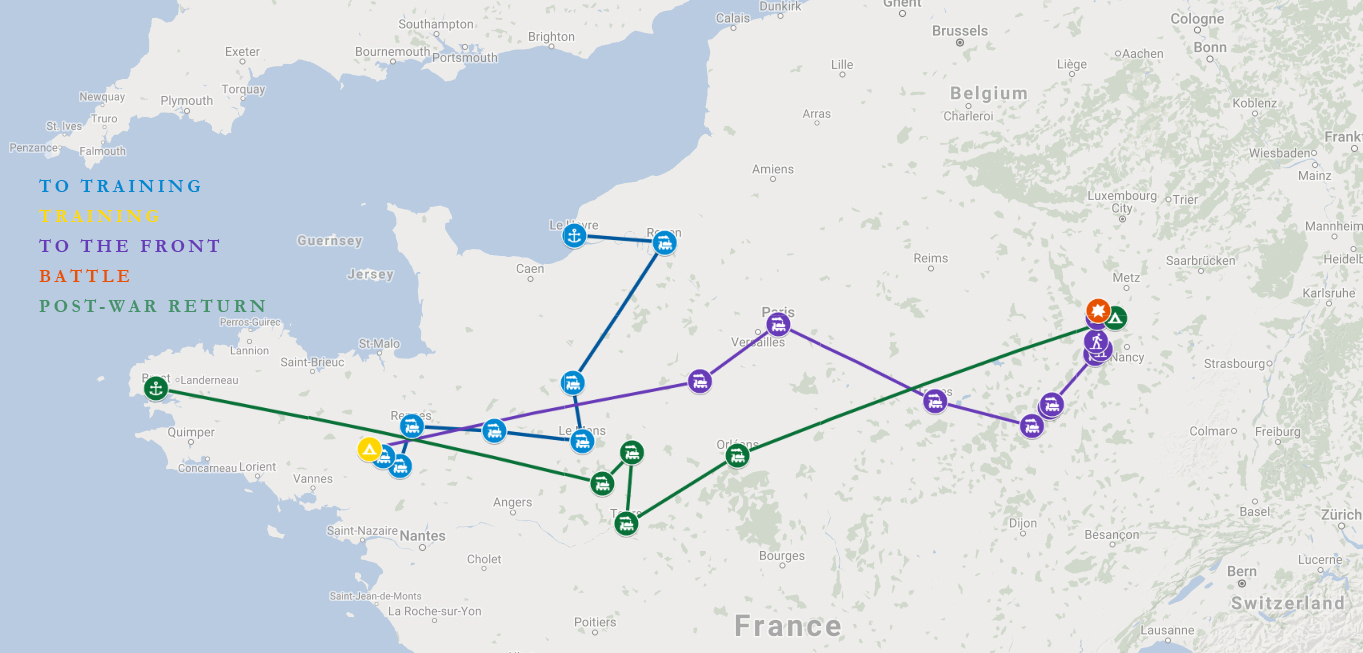

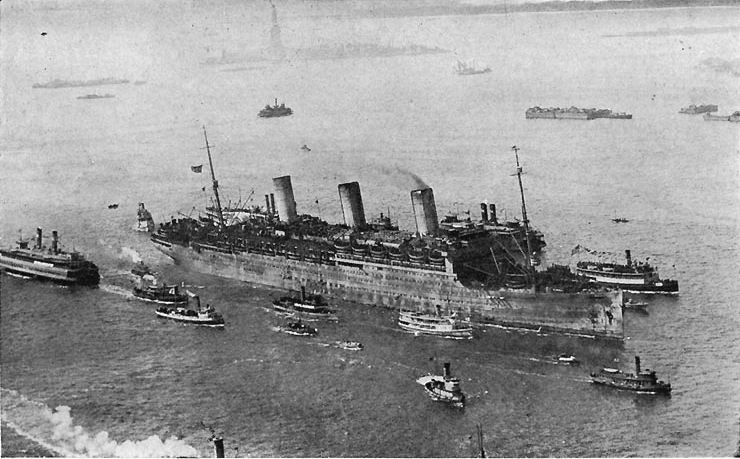

Battery C left Camp Custer on July 16th, traveling by train to Camp Mills on Long Island, New York, a “city of tents” where they arrived at midnight in a drizzling rain and stayed until the end of July. They boarded the British Steamer Maunganui for their overseas transport on July 30th, 1918.

The Girl They Left Behind

Their ship was part of a convoy, a “spectacle as it sailed down the harbor of New York, out into the sea … out past the girl every man left behind…the good old Statue of Liberty.” The convoy “assumed a formation protected by a British cruiser and an American destroyer which took the lead, small sub-chasers describing a circle around the convoy, and two seaplanes circling overhead.” Thus began their 12-day journey to the Old World, disembarking in Liverpool on August 11th amid whistlings and cheers of the gathering crowds and embarking on a train to Southhampton on the southern English coast.

Their ship was part of a convoy, a “spectacle as it sailed down the harbor of New York, out into the sea … out past the girl every man left behind…the good old Statue of Liberty.” The convoy “assumed a formation protected by a British cruiser and an American destroyer which took the lead, small sub-chasers describing a circle around the convoy, and two seaplanes circling overhead.” Thus began their 12-day journey to the Old World, disembarking in Liverpool on August 11th amid whistlings and cheers of the gathering crowds and embarking on a train to Southhampton on the southern English coast.

The following day they sailed to Le Havre, France, lying in the harbor all morning waiting for the tide to come in. It was the first of many stops in that war-torn country. It was outside of Le Havre they got their first dry wash: “a brisk massage of the entire face and body with the dry hands was considered to be enough to give us the semblance at least of cleanliness, and in after months it turned out to be sufficient as we really had no means of bathing.”

They traveled through the French countryside on their way to Camp Cöetquidan, an historic French camp used for military training since Napoleon’s time. The battery spent two months training at Cöetquidan “in all branches of artillery work with the French 75’s and the last few weeks before we left we were simulating actual conditions at the front.”

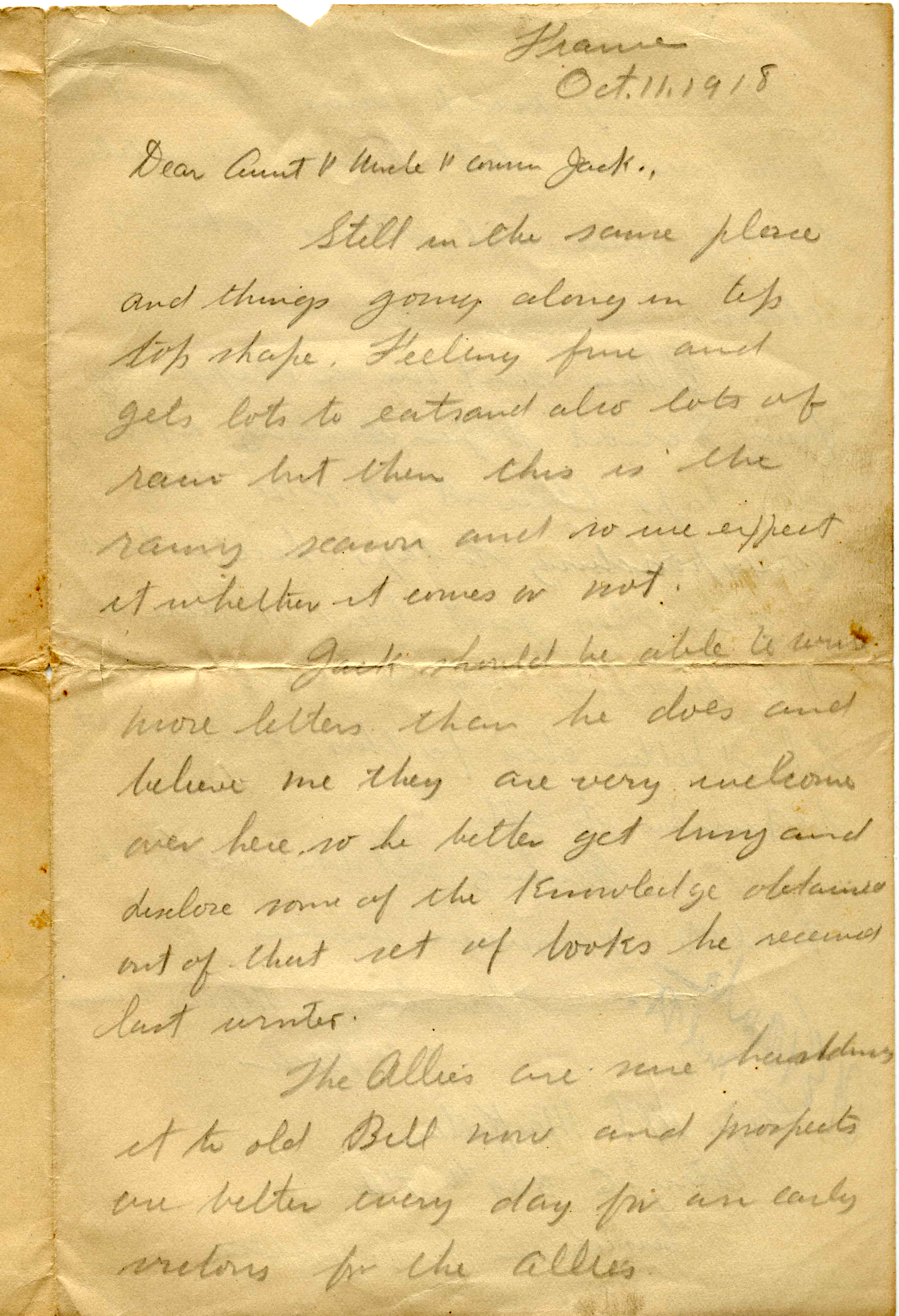

Mac took advantage of the training time to send a picture home to his aunt (my grandmother Sarah Livingstone [later McCrie]) with a message on the back revealing his sense of humor:

Aunt Sarah: Taken Oct. 6/’18 Somewhere in France. Guaranteed Hole proof hats. My partner has a gas mask enclosed in the satchel and as you will note we are both equipped with burglar alarms. With best to yourself and family. Mac.

He also wrote a letter on the 11th to his aunt Belle (nee Livingstone) Duffy in which he expressed optimism for an early Allied victory.

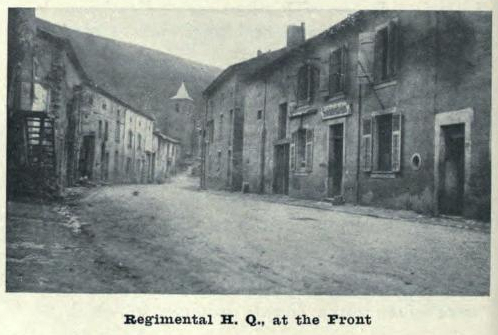

Battery C was issued its complement of supplies, horses, and materiel and left on October 23rd by train for the front. Again crossing much of France, they arrived at Domgermain on October 30th, where the rest of their trek would be on foot. “Since then our artillery has been on foot and has seen a bit of France at that. After detraining we marched about two miles towards Toul and camped out in our pup tents. The next morning our shelter halves were so stiff with frost we could hardly roll our packs.” Apparently the field soldiers, like in Civil War days, each carried half a tent and paired off with a fellow soldier for the night. It was near Toul they saw their first air fight, as a German plane “came over to do some observing, but hundreds of shots from anti-aircraft guns drove the Boche (German) high up into the air where he could not see anything of advantage to him.”

The Sights and Sounds of War

Moving northeast toward Metz, “the roar of the guns kept getting sharper and we realized we were drawing nearer to the front.” That sensation was reinforced when passing through the badly shelled towns of Bernecourt and Flirey, where there was “hardly a wall left standing.” On November 1st they reached Mort Mare Woods (Bois de Mort Mare), where they stayed a few days. A network of German trenches and dugouts, reinforced with concrete and iron, showed the Germans had planned a long occupation and only weeks before had abandoned their ammunition, machine guns and supplies as they pulled back. The action wasn’t over, though.

On the 5th of November Battery C moved out. “We were not exactly scared but a queer feeling came over us, as we were marching along in the darkness, not knowing whether we were going right into action, or not.” The next night “we went forward under cover of darkness, scheduled to pass through Thiaucourt, a large city which had recently been held by the Germans but recaptured. But the Boche was favoring the town with a harassing fire of gas shells, and it was necessary to take a circuitous mud road around the place. … The first night was a night of uneasiness to most of our valiant warriors, as the shells were falling around us all night and it was our first experience under real shell fire.”

The ammo dump was a few kilometers away from where they took up position, and troops sent to resupply the guns saw a German plane fly over, and shortly thereafter “shells began flying all around the dump, but luckily not one burst near the ammunition. The entire trip back was one continual round of explosions and the road was bright as day from the bursting shells.”

The next night was worse. “This night we experienced a heavy bombardment with gas and the night being foggy, the valleys were loaded to the brim for hours.” The battery was ordered to dig in the next day, which they spent all day doing, and on the 9th “the firing data, including a range of 4,000 meters, was sent down, and when the command to fire was given, our first message to the Boche was sent hurling over in the form of shrapnel.” On the evening of the 10th “as it grew dusk all the guns of the battery started to fire, and one session followed another in rapid succession throughout the night.” They stopped at 7 a.m. on the morning of the 11th of November.

The war ended that day at 11:00 a.m. — the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month — but “at just five minutes to eleven, two big shells came over from Fritz and landed alongside our positions, a parting farewell, as it were.” And that was that. Mac and his battery saw about a week of action on the front.

The Return Home

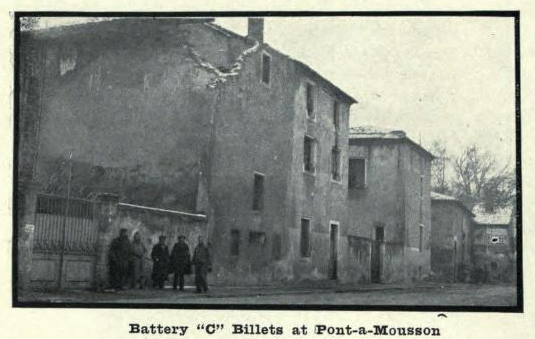

The battery spent the next three months in the nearby town of Pont-à-Mousson on the banks of the Moselle River, reflecting on their experiences and, on Thanksgiving Day, offering up

“a prayer truly of thanksgiving that we had been brought safely through these months of the most terrific warfare the world will ever witness, and that this old earth will ever in the future be a safe place for all humanity to live in and enjoy the fruits of its labor.”

If only.

The regiment celebrated Christmas in Pont-à-Mousson, decorating the walls “with views of Detroit, the Statue of Liberty, Uncle Sam,” and holiday greetings.

The regiment began their trek back to America on February 11, 1919, by boarding a train in Dieulouard and wending their way through France. “The valley of the Loire was particularly interesting—many chateaus, rugged hills and beautiful woods appearing before our eyes. We passed through many towns on our way eastward, as it seemed we were always bound to wander across a great part of France, apparently the French way not being to go from one place to another in the most direct route.” They finally ended up in Brest on the west coast, and on March 26th boarded the Leviathan, an aptly named ship carrying 12,274 soldiers and a crew of 2,000 for her cross-Atlantic cruise. “We…passed that beloved old girl ‘Statue of Liberty’ about nine o’clock on the morning of…April 2nd. Such rejoicing as we passed up the harbor!”

They left Camp Mills in New Jersey on April 17th and arrived in Michigan the next day. A half-hour stop at the Michigan Central station in Detroit was a short, joyous homecoming before continuing to Camp Custer. On April 23rd his military stint finally ended, and Mac became a civilian again, on his way back to Detroit and his wife Edna.

After the War

Malcolm returned to his job at the Anderson Electric Car Company, now working as a cost accountant. He and Edna started a family, with son Glenn born in May of 1923 and Donald in July of 1926. About the same time Mac switched gears from accounting to sales, now working as a representative of Yates Woolen Mills.

According to a 2016 article in The Oakland Press, in 1923 Malcolm established MacKellar Associates, “representing two woolen mills and selling woolen body cloth, upholstery and headliners to the automotive industry. Customers included Packard Motor Company, Studebaker, and the ‘Big Three.’ The original office was located in the historic General Motors Building in Detroit. It continued as a one-man sales operation and secretary for 20 years. Then, Malcolm’s sons, Glenn and Don MacKellar joined the company and they expanded their product line with injection molded plastics and decorative metal parts.” The family-owned company continued to expand and is now in its fourth generation of MacKellars.

A family note states that Malcolm, who had a summer home in Boyne City, was an “executive type organizer, free spender, money maker, expansive.”4 Mac’s wife Edna was also apparently socially adept, becoming the president of the Rosedale Progressive Club in 1945 as reported in the Detroit Free Press.

Mac passed away in January of 1957 at age 64, following a heart ailment. His wife survived another twenty years, passing away in August of 1977. Malcolm’s remains were buried in Grand Lawn Cemetery in Detroit. His older sister Katie, who died in 1986 at age 97, is buried nearby.

Mac’s story is an interesting tale, one reflecting its time and country: an immigrant orphan raised by his grandmother, aunts and uncle; who rose to the top of his class in public school, served overseas in a World War, started a small business, and made a good life for himself and family in his adopted land. It could serve as a model for the nation in our current era.

Mac was a guy who passed Army muster, passed through mustard gas, and undoubtedly passed the mustard across the family table. As they’d say in the Army, he seemed pretty squared away.

Endnotes:

1 Hugh Ronald joined the North Carolina infantry in 1861 and was home on extended sick leave a week later. He was separated after a few months when it became clear he was not returning. Barney Anthony joined the New York infantry in 1863 and trained for 3-1/2 months before being rejected for physical disability (old age) as his unit was preparing to deploy.

2 William Estall was discharged from his regiment, being found unfit for further service in 1879 after his extensive visits to the infirmary. His step-son Thomas committed suicide while stationed in Eqypt in 1910. Andrew Templeton deserted the Gordon’s Highlanders infantry unit in 1864 shortly after joining and fled from Glasgow to Canada.

3 Sarah (nee Campbell) Livingstone, Malcolm’s maternal grandmother, had a penchant for adding vowels to surnames. When she married into the Livingston family, she added an “e” to the end of the name, making it Livingstone. When she took in her orphaned grandchildren, she added an “a” to their name, going from McKellar to MacKellar.

4 Characterizations of the MacKellar family are from family history notes left by Margaret (nee McCrie) Mead, a cousin of Malcolm MacKellar. See Livingston Family History at http://genealogy.thundermoon.us/history/livingston%20family%20history.pdf

5 Edna Persinger’s father worked as a foreman at an auto company, and her sister worked as a clerk at Anderson Electric Car Company. It is probable that Edna, a stenographer, also worked at Anderson.

6 “Horses in World War I,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horses_in_World_War_I

We were intrigued with the life of Malcolm as presented in your well-researched essay. The fleshing-out of this relative gives us a real understanding of life at the time and the history he made. It is the immigrants that made our nation what it is today, and made our lives possible.Once again, thank you for sharing all of the information.

We were intrigued with the life of Malcolm as presented in your well-researched essay. The fleshing-out of this relative gives us a real understanding of life at the time and the history he made. It is the immigrants that made our nation what it is today, and made our lives possible. Once again, thank you for sharing this information.

Thank you very much for your posting. I am a Grandson of Glenn MacKellar and learned a lot about Malcolm and the family.