Family Fonts

Font

• A receptacle in a church for the water used in baptism, typically a free-standing stone structure.

• A source of a desirable quality or commodity; a fount. Example: “they dip down into the font of wisdom”

— from Lexico.com, in association with the Oxford University Press

My sister Beth and I traveled to London this year in search of ancestral haunts. What we found was ancestral fonts:

• Baptismal fonts in churches where our ancestors were christened, and

• London pubs, those classic fonts of British ale, which were associated with our great-grandmother.

This is the story of finding those fonts.

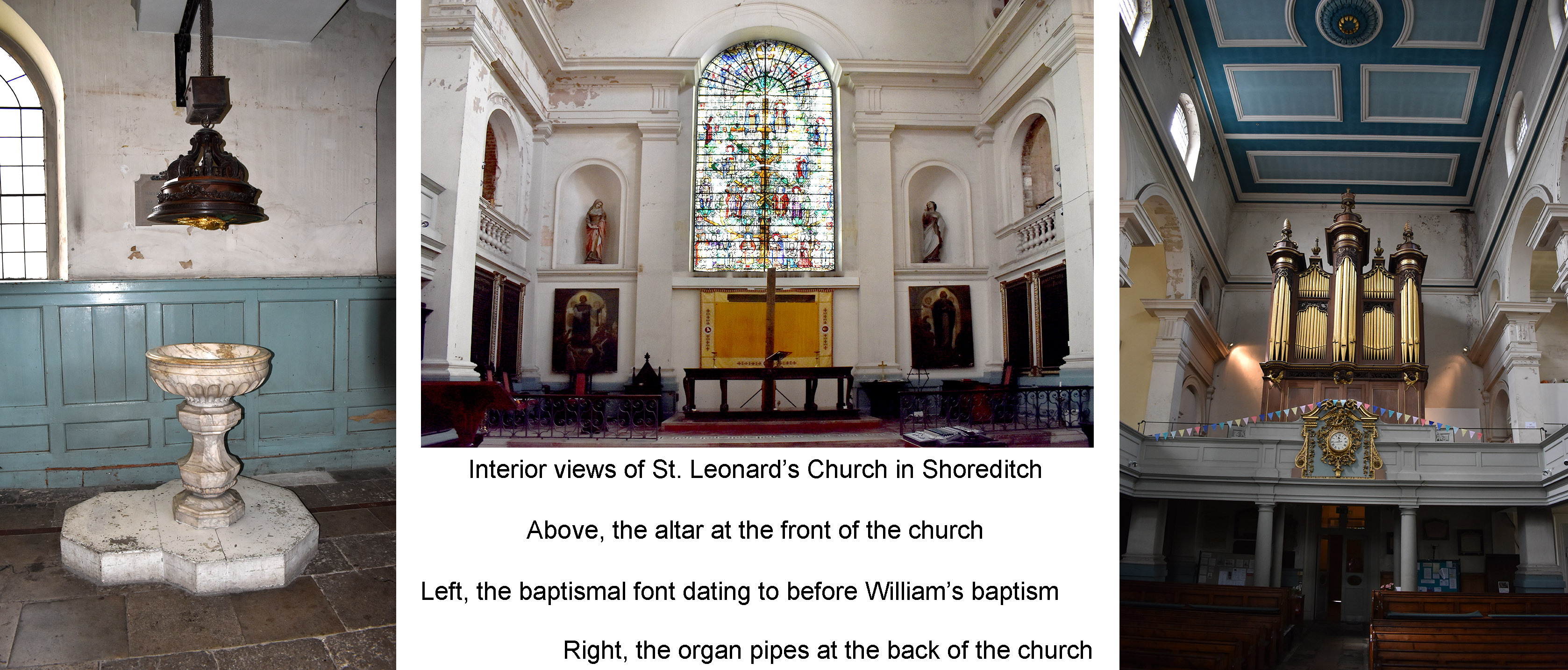

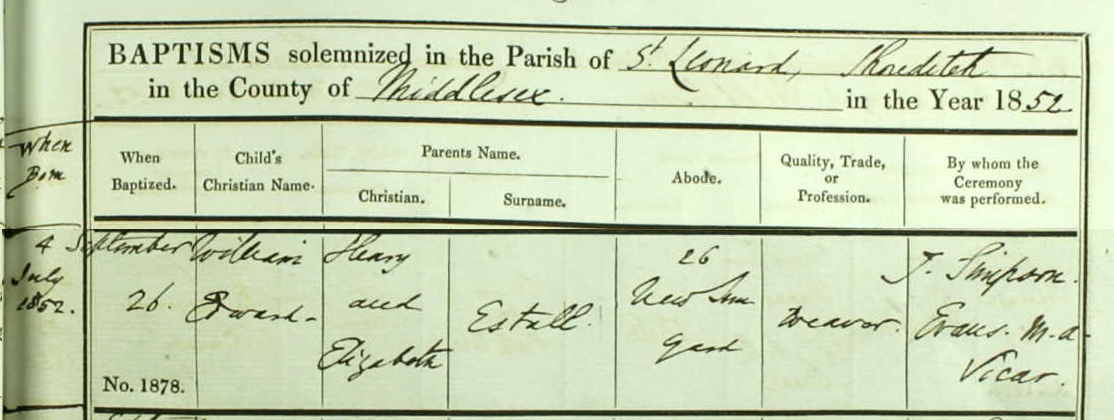

Our first font, of the baptismal variety, was found in the crumbling St. Leonard’s Church in Shoreditch. We went there because our great-grandfather, William Estall, was born in Shoreditch in London’s East End in 1852. He came into the world on New Inn Yard, a street that has changed many times over the years. In the late 1500s the area housed London’s original playhouse, The Theatre, where Shakespeare cut his teeth as an actor and playwright. The globe map on the right shows The Theatre in relation to New Inn Yard. [Click on it to enlarge.]

As we sat across the street from the location where William Estall was born we could see the site where a recent archeology dig uncovered the foundations of the Theatre. It was torn down in 1598 and moved across the River Thames and rechristened The Globe. Likewise, a couple hundred years later William Estall’s birthplace was constructed and that too was later torn down. Though we couldn’t see either structure, we let our imaginations travel back in time to see a pensive William Shakespeare stroll along the lane and a swaddled William Estall being whisked off to the nearby St. Leonard’s church in his mother’s arms.

William Estall was baptized in September 1852. We found St. Leonard’s Church (also known as the Actors’ Church due to its use by The Theatre’s owners and actors), but it was covered in scaffolding and our hearts sank knowing that we wouldn’t be able to see inside it. Beth, however, walked into its soup kitchen for the homeless, and the gentleman running it said he’d try to find a way inside for us.

William Estall was baptized in September 1852. We found St. Leonard’s Church (also known as the Actors’ Church due to its use by The Theatre’s owners and actors), but it was covered in scaffolding and our hearts sank knowing that we wouldn’t be able to see inside it. Beth, however, walked into its soup kitchen for the homeless, and the gentleman running it said he’d try to find a way inside for us.

He breezed us by a construction worker who warned against our entry, over debris, down dark stairways, and finally found a door into the unlit church. And there, sitting off to the side, was the font, the very one used to baptize wee Willie.

As we gazed on it, a sense of how fleeting our lives are gnawed at me. The infant William grew into a man, fathered our grandmother Bessie, and passed away. His infant daughter grew into a woman, mothered our father, and subsequently passed away. And here we were, in the senior years of our lives, feeling the smooth surfaces of the font — feeling a connection to one who went before us — knowing that our time too was limited. In a way, the font was like a stone marker — not a headstone commemorating a death, but one commemorating the start of a life and of the string of lives to follow.

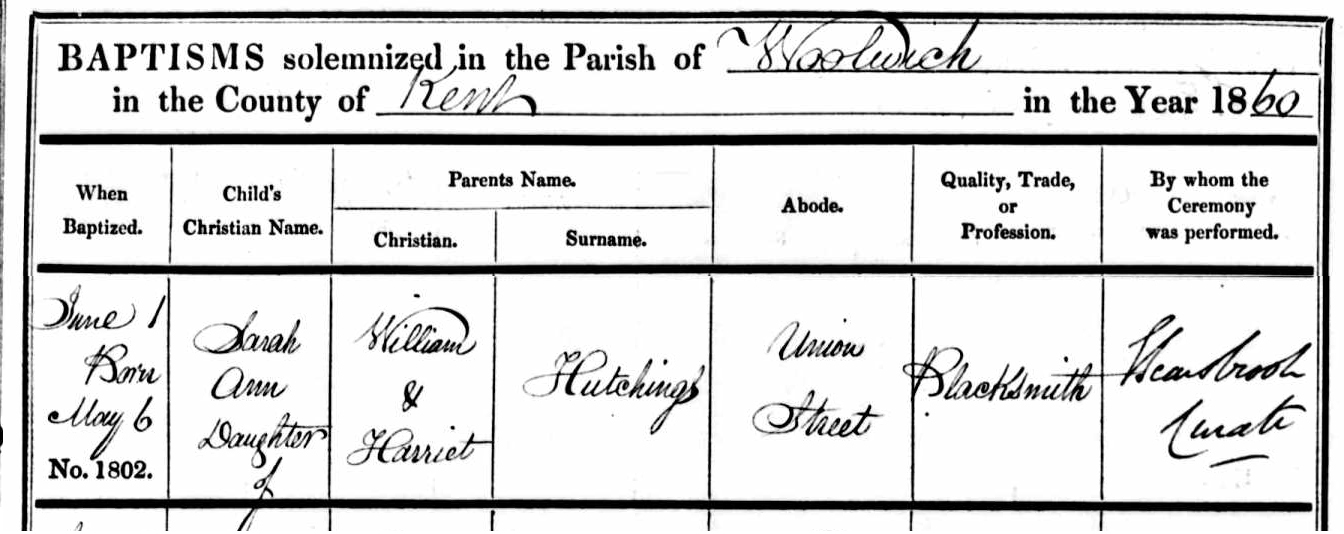

Having found Bessie’s dad’s baptismal font, we were also fortunate enough to come across her mother’s. This was when we visited St. Mary Magdalene Church in Woolwich, south of the River Thames. After a morning of contemplating time and the universe via the clock and astronomical exhibits at Greenwich, we took a bus to Woolwich to visit the streets our great-grandmother Sarah Ann Hutchings once graced with her young presence.

Having found Bessie’s dad’s baptismal font, we were also fortunate enough to come across her mother’s. This was when we visited St. Mary Magdalene Church in Woolwich, south of the River Thames. After a morning of contemplating time and the universe via the clock and astronomical exhibits at Greenwich, we took a bus to Woolwich to visit the streets our great-grandmother Sarah Ann Hutchings once graced with her young presence.

The highlight of the afternoon was visiting St. Mary Magdalene Church, the mother  church of Sarah and her family. Of course the door was locked, but we rang the bell and were escorted in by a kindly lady running the church’s daycare center who showed us around the inside of the church. My eyes were immediately drawn to the stone font near the front of the church, where our great-grandmother Sarah, her mother, and her grandfather were baptized in 1860, 1838, and 1817 respectively. The church is also where Sarah’s great-grandparents were married in 1804. This building holds a special place in our history.

church of Sarah and her family. Of course the door was locked, but we rang the bell and were escorted in by a kindly lady running the church’s daycare center who showed us around the inside of the church. My eyes were immediately drawn to the stone font near the front of the church, where our great-grandmother Sarah, her mother, and her grandfather were baptized in 1860, 1838, and 1817 respectively. The church is also where Sarah’s great-grandparents were married in 1804. This building holds a special place in our history.

One good font leads to another, and we walked from the church to the nearby pub where Sarah lived and worked as a barmaid at the time of the 1881 census. The Mitre pub is undergoing renovation on the inside but the outside is virtually unchanged from the time Sarah worked there.

Disappointed that we couldn’t have a drink there in her honor, we continued through town along the high street, turned down the lane where she lived at the time of her baptism (Union Street then but today called Macbean), and over to the market square. The market fronts on the Royal Arsenal Gate and the arsenal beyond it where her father, a blacksmith and engine fitter, probably worked. Her ‘step-father,’1 Robert Billinghurst, also worked at the Arsenal, in his later years as a foreman.

As was our custom, we took a mid-afternoon break at a pub, in this case the Dial Arch, a former gun factory on the Royal Arsenal grounds, where Beth had a Pimm’s and I had a cask ale. While slaking our thirsts and resting our feet we could gaze at the ornate Royal Brass Foundry where guns were cast from the early 1700s until 1870. This would have been one of a number of buildings where Sarah Hutchings’s father worked his blacksmith trade.

Also noteworthy about the Dial Arch is that it was the birthplace of the Arsenal Football Club in 1886, which went on to become one of England’s premier teams. A marker in the shape of a soccer ball can be seen in the bottom left corner of the photo.

Our toast to Sarah was delayed but not denied.

The Mitre was not the only pub where our great-grandmother Sarah lived.

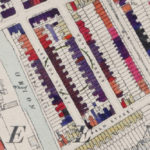

Circle: V-2 Rocket impact

Black: Total destruction

Purple: Damaged beyond repair

Red: Seriously damaged

Shortly before our trip to London I was browsing historical maps to find an old family neighborhood in Bethnal Green, namely the area where William Estall once lived on Totty Street and Sarah Hutchings later lived on nearby Palm Street. This neighborhood was badly damaged by German bombing during the Second World War [see map at left] and the city decided to turn it into a park. I thought a stroll through the park would be a quiet way to contemplate and pay tribute to our ancestors.

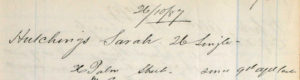

As I was looking at a satellite image I was struck by the presence of a lone building surrounded by acres of parkland greenery and ponds. I switched to street view and saw that the building was the Palm Tree Pub. It looked like it was situated about where the former Palm Street lay. When I looked at the address painted above the door it seemed vaguely familiar and I began digging through Bethnal Green workhouse records to find the address where Sarah Hutchings lived in 1887.

Amazingly, the address on the building, numbers 24 and 26, showed it was where our great-grandmother Sarah lived in 1887. This was almost like a cosmic sign, the only building still standing in the neighborhood is where Sarah called home for a time. What kismet. Oh, we HAD to have a drink there!

Our first attempt was thwarted by a security guard who informed us the pub was being used for filming a television show. (It turns out that a few movies and shows featured the pub due to its old-time atmosphere.) But hey, it was mid-afternoon, time for a drink and a sit-down, so we found another nearby pub, this one also from the Victorian age. A kind local patron there heard our story and walked back to the Palm Tree to see if he could get us in (Londoners were nothing if not helpful to us) but the security guard was unmoved. So the Palm Tree was put off for another day.

Delayed, but not denied

On a beautiful Sunday afternoon, after service at the church where our grandmother Bessie was baptized —yet another visit to a family font — Beth and I walked over to the Palm Tree Pub to finally have a toast to our great-grandmother Sarah Hutchings.

When we entered the pub we stepped back in time — 132 years to be exact — to a place where Sarah would have undoubtedly had a pint or two before retiring for the night upstairs.2 Perhaps she even worked the bar.

But running the bar today was its 80-year-old owner, Alf Barrett, who served our drinks with a twinkle in his eye and regaled us for an hour or two on the history of the area, including his rotten luck to have bought the pub right before the city demolished the temporary housing erected after WWII (eliminating much of his local clientele) and turned the neighborhood into a park. But Alf, and the Palm Tree, are still standing, and between its jazz music, scarlet lighting, and retro atmosphere, it’s in much demand today. Alf was kind enough to comp Beth a free glass of wine given her winning personality and connection to the site. Sarah Hutchings would have been pleased.

Alf also helped us understand something about our great-grandfather William Estall. William was a dock worker according to our grandmother’s birth certificate. I assumed he worked the wharves along the canal that runs through Bethnal Green. But Alf was the third person on this trip who said he must have worked the docks by the River Thames. I told him I thought that was too far away, but Alf assured me it’s not — in fact, he worked there when he was a youth. So I’ve settled the issue in my mind: William was one of the hundreds of men who showed up every day for a chance at work at the docks down by the Thames.

Alf advised us to visit the Museum of London Docklands on the Isle of Dogs to get a sense of their lives. It looked to be hard, physical labor, and except for the “favoured casuals” (day laborers) it was hit or miss to catch a day job.

“The favoured casuals were known as ‘royals’, the aristocrats of the casual workforce. If more men than the royals were needed, then the foreman would select the fittest-looking from among the other casuals. One method of doing this, albeit rarely employed, was to throw brass tickets – the guarantee of entry and work – into the waiting crowds and watch the men scrabble and fight to pick them up. The toughest and best suited for the work ahead would secure a winning place by using their brawn and not their brains. Those who missed out would have to wait until next time.”

— Historical Eye, “Top of the Docks,” https://historicaleye.com

Alf also recommended we partake of the Sunday Roast at the nearby Narrow restaurant on the river at Limehouse. It was a great recommendation: the food was good, the gin and tonic tasty, and the view spectacular.

Hats off to good ol’ Alf, he was a font of information.

1. Sarah’s mother Harriet took up with Robert Billinghurst shortly after Sarah’s father died. Robert was still legally married at the time and there is no indication that he ever adopted Sarah, she maintaining her birth father’s surname until her own marriage in 1891.

2. Though the original building was replaced in 1935, it was built along the same lines and at the same place as the original according to historical sources.