What I Learned

The point of visiting historical family sites is to connect in a sensory and an emotional way with your forebears. The trip my sister Beth and I took to London this year fulfilled that goal.

Walking neighborhood streets and visiting homes, schools, and churches does a number of things. First, it de-mythologizes the past. Researching ancestors and their environs from afar often renders people and places exotic, bigger-than-life, their images refracted through our own imaginations or the viewpoints of authors and historians. But walking the streets makes the places real and the people more immediate because we have a first-hand setting to put them in. Although we can never hope to really know the ancestors we’ve never met (and let’s face it, how well do we really know the people we do meet?), walking a mile in their shoes at least makes them approachable.

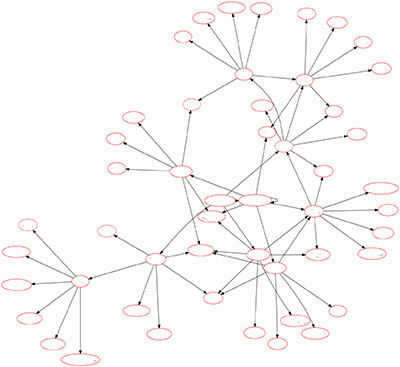

Second, visiting places and walking neighborhood streets helped us to orient places, distances, and times in our mind. We made spacial connections in our brains that mirrored the geography. We know that two blocks away from the birth home of our grandmother was her baptismal church, within earshot of its bells; how close her school was; how tightly the family’s various homes were clustered. It’s like a web of locations is formed in your mind, orienting and unifying a sense of the whole.

Second, visiting places and walking neighborhood streets helped us to orient places, distances, and times in our mind. We made spacial connections in our brains that mirrored the geography. We know that two blocks away from the birth home of our grandmother was her baptismal church, within earshot of its bells; how close her school was; how tightly the family’s various homes were clustered. It’s like a web of locations is formed in your mind, orienting and unifying a sense of the whole.

Third, our ancestors and their stories are internalized more vividly when we visit where they lived. It’s the difference between the two-dimensional experience we get from researching documents, maps, and pictures on paper versus the twelve-dimensional experience of visiting a place. If that sounds like an exaggeration, consider the multiple dimensions of height, width, and depth (e.g., how big is the place?); location (where is it, and where in relation to others?); time (historical, as well as transit between places); sensory dimensions of sound, sight, smell, taste, and touch; and the thoughts and emotions imprinted as the memory is formed.

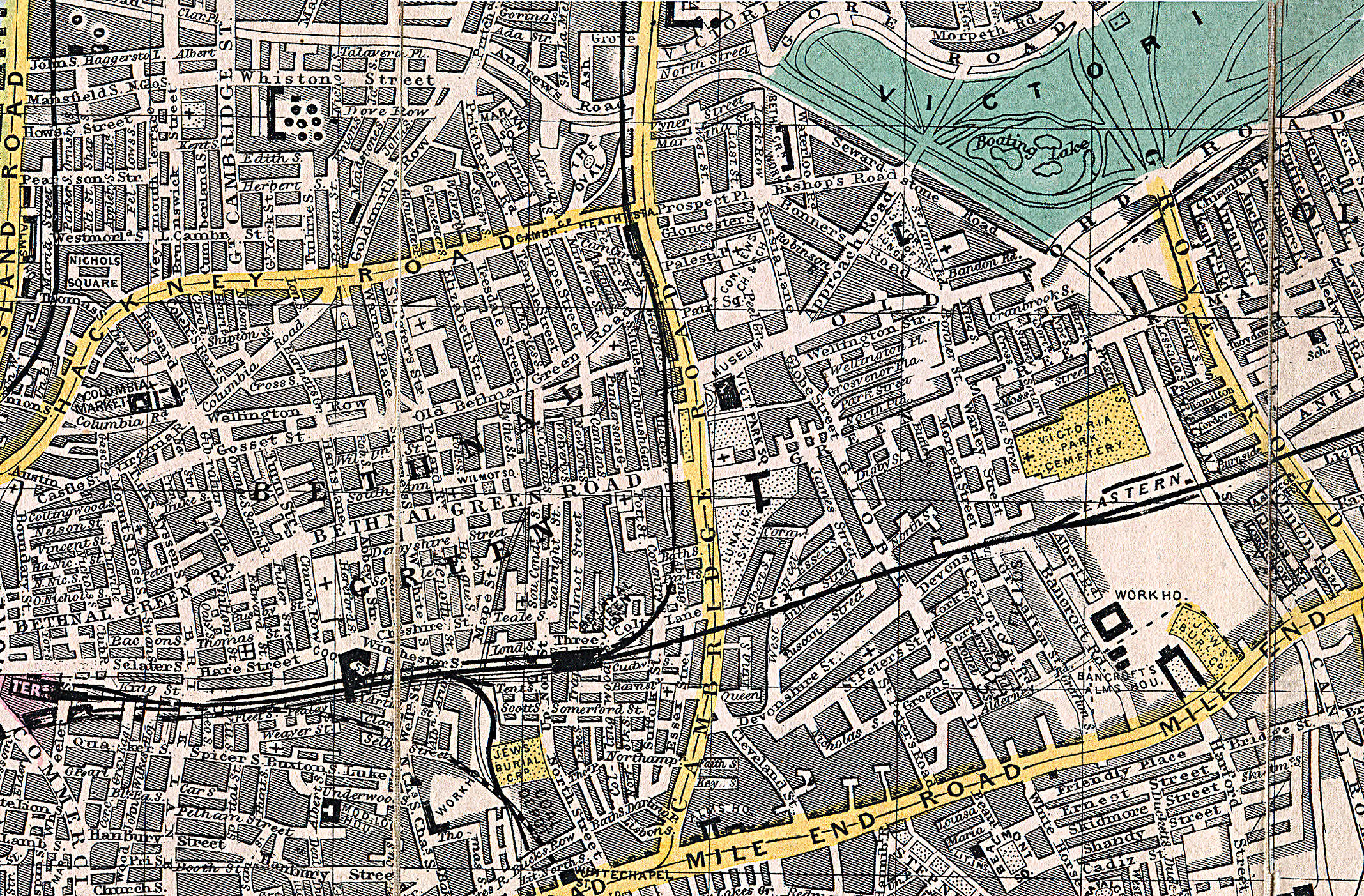

Take for instance the visit my sister and I paid to the Palm Tree Pub in Bethnal Green, a place over which our great-grandmother lived in 1887. I’d seen the pub location on an old map and I’d seen the building on satellite and street views on Google. Those were two-dimensional experiences. On visiting there, however, we now have a strong impression of the place: its location close to the Regent’s Canal (we walked along the canal on the way there); its size; its proximity to other places; its look and feel; the sound of conversations at the tables and bar; the taste of the ale; the Victorian decor. And overlaying these physical impressions were the thoughts shared by the octogenarian barkeep on the history of the neighborhood, as well as the warmth of camaraderie, humor (the owner had a sharp sense of it), wistfulness at being where our great-grandmother called home, and ease at enjoying a pint in a friendly and restful place. Two versus twelve dimensions: you can guess which made the bigger impression, the stronger memory, and brought history more to life.

Take for instance the visit my sister and I paid to the Palm Tree Pub in Bethnal Green, a place over which our great-grandmother lived in 1887. I’d seen the pub location on an old map and I’d seen the building on satellite and street views on Google. Those were two-dimensional experiences. On visiting there, however, we now have a strong impression of the place: its location close to the Regent’s Canal (we walked along the canal on the way there); its size; its proximity to other places; its look and feel; the sound of conversations at the tables and bar; the taste of the ale; the Victorian decor. And overlaying these physical impressions were the thoughts shared by the octogenarian barkeep on the history of the neighborhood, as well as the warmth of camaraderie, humor (the owner had a sharp sense of it), wistfulness at being where our great-grandmother called home, and ease at enjoying a pint in a friendly and restful place. Two versus twelve dimensions: you can guess which made the bigger impression, the stronger memory, and brought history more to life.

I feel closer to my grandmother Bessie’s extended family because of this trip. I have a better framework from which to understand their stories. In a sense, the play’s scenery and props have now been added so that the action on stage seems more real.

Along the way I also learned:

• That Bethnal Green is smaller than expected. I had wondered how my great-great grandfather had moved his family so often from its western to eastern sectors, but having been there I realize it wasn’t far at all, just a few minute’s walk. In the words of a local historian, Bethnal Green was an insular world, like a town which some people never left. It was a neighborhood seen from the outside, but it was a universe seen from within.

• Similarly, walking from the parish of Whitechapel to Spitalfields and on to Shoreditch and Bethnal Green — all of which were at one time home to the various generations of the Estall families — was surprisingly easy. I’d previously thought that the family “migrated” over the years from parish to parish, but now I think of it as just moving around the corner. Along the same line, the distance from Bethnal Green to the River Thames, where the East and West India Docks were located, was also a walk-able distance, explaining how our great-grandfather could make a living as a dock worker.

• Our earliest Estall forebears were tallow chandlers, and one of them, John, apprenticed through the Tallow Chandler Company, i.e., the guild. We found John’s entry in the register at the Guildhall Library, but the Tallow Chandler Company’s archivist couldn’t find any other evidence of the family’s association with the guild. She wrote me while I was there, “I’m afraid we have no records on our historical database [other than the apprentice entry] for anyone by the name of Estell or Estall, likely because John and William never became Freemen or Liverymen of the Tallow Chandlers Company, as it was rather expensive to become a member for most tallow chandlers.” This confirmed my suspicion that the early Estall families were not among the poorest in their neighborhood, but neither were they among the most well off.

• Having said that, I also got the sense that the later Estall families lived normal lives of the lower working class rather than the grueling lives of abject poverty portrayed in many accounts of that time and place. The flat where my grandmother was born, for example, was in an attractive brick tenement rather than a dilapidated structure. The pubs over which my great-grandmother lived before her marriage were striking, substantial buildings. The school my grandmother attended is architecturally pleasing and still vibrant. Though most of the other buildings our ancestors inhabited no longer stand, the impression we got from those that do is that these were not places of squalor. The neighborhood may have had many pockets of poverty — this was after all the notoriously poor East End — but our families, though apparently struggling, didn’t necessarily sink into the bottom of them.

• The role of the church in the community, and even in the family, came into focus as we visited the sites of family baptisms, marriages, and burials. Sitting in the same pews, attending a service, and gathering around the same baptismal fonts as did our ancestors gave us a sense of the potential comfort and reassurance of ritual that may have succored our families over the years. Reinforcing that was the way every church we visited still reaches out to the poor of their neighborhoods, offering food and services to the needy. Since our relatives appeared to reach only the lower steps of the economic ladder, the church may have been a place where they felt welcomed and untroubled and even validated.

• Pub culture, past and present, was a real factor of the neighborhoods. This is where neighbors and workmates got together for a pint and socialization. My impression is that our great-grandmother Sarah Hutchings, who lived above two pubs at various times, was no stranger to alcohol (she was once a barmaid after all), and her husband William, a general labourer, probably was not either. Whether they over-imbibed is unknown, but with the plethora of pubs in their time, and even the number of well-attended pubs in the present day, they wouldn’t have likely been teetotalers either. London is a pub culture, which knits people together, and to know its pubs is one way to know a neighborhood.

On a side note, in the 10 days we were in London I figure we enjoyed drinks in at least 20 of them. One of the more memorable stops was the Kings Arms in Bethnal Green. This pub, a bit off the beaten path and quite informal in atmosphere, had by far the greatest number and variety of cask and keg ales on tap, displaying a list of them and their origins on a large wall-mounted board. And what particularly endeared the pub to me was that while we were there a tune came on the radio that perked up my ears: the Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour after which this vacation and series of blog posts was named.

I learned a lot about the family on this trip and feel even closer to them. It was quite magical.