In a previous post we looked at the early life of Hermann Schütze, our great-grandfather, in the Dresden and Hamburg areas of Germany before he emigrated to America in 1880.

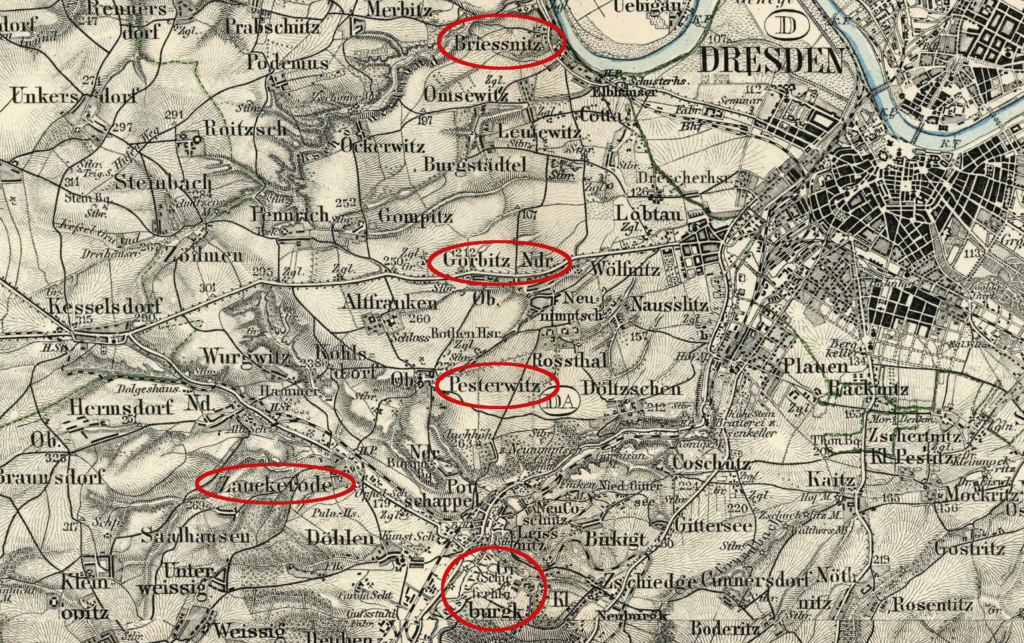

With the help of German church records we’ve now traced Hermann’s ancestral line back another six generations to its 17th century roots in the area just northeast of Dresden, which is the subject of this post.

Special thanks to Hugh Davis and Freimut Kahrs who started us on this journey.

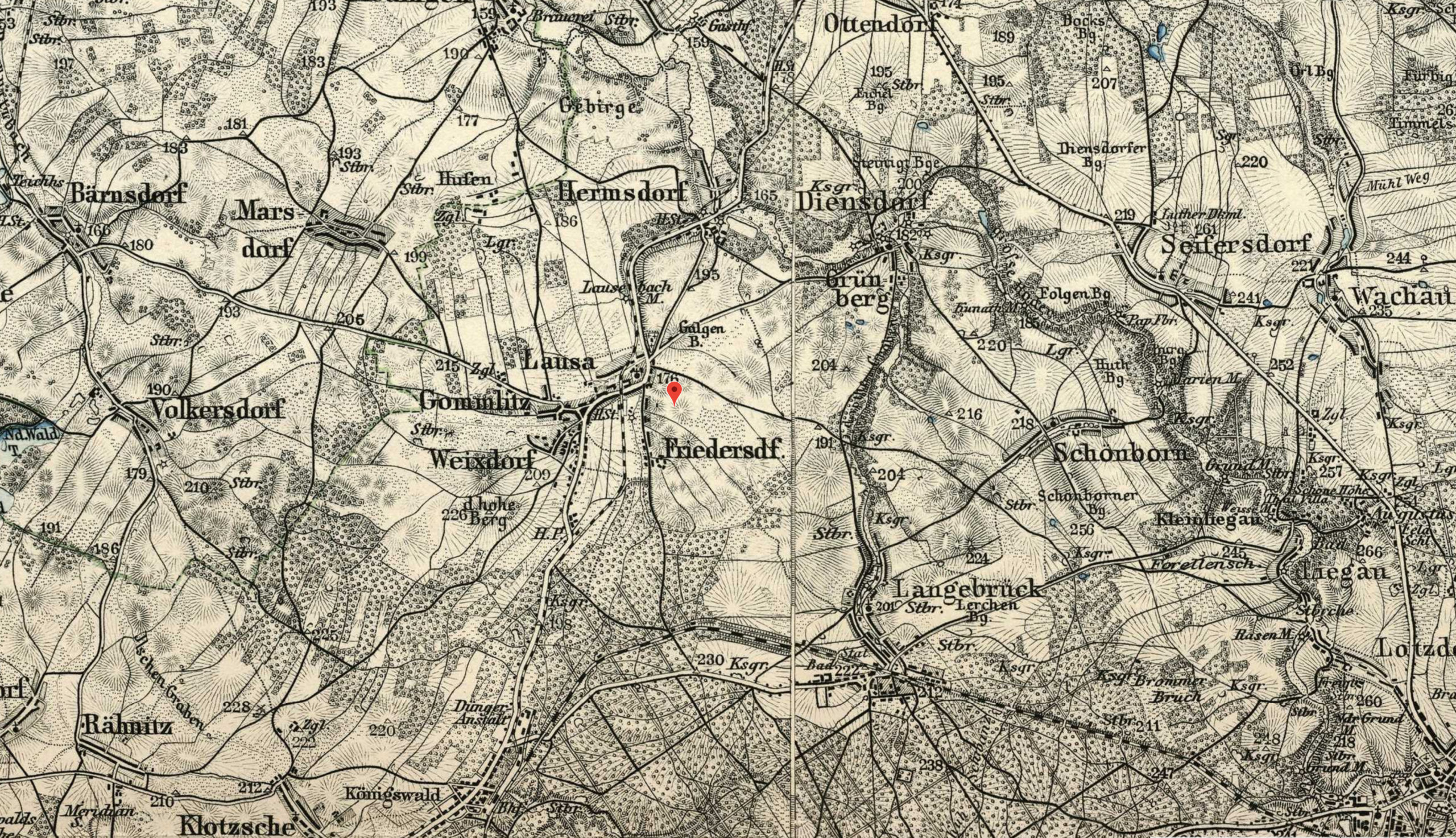

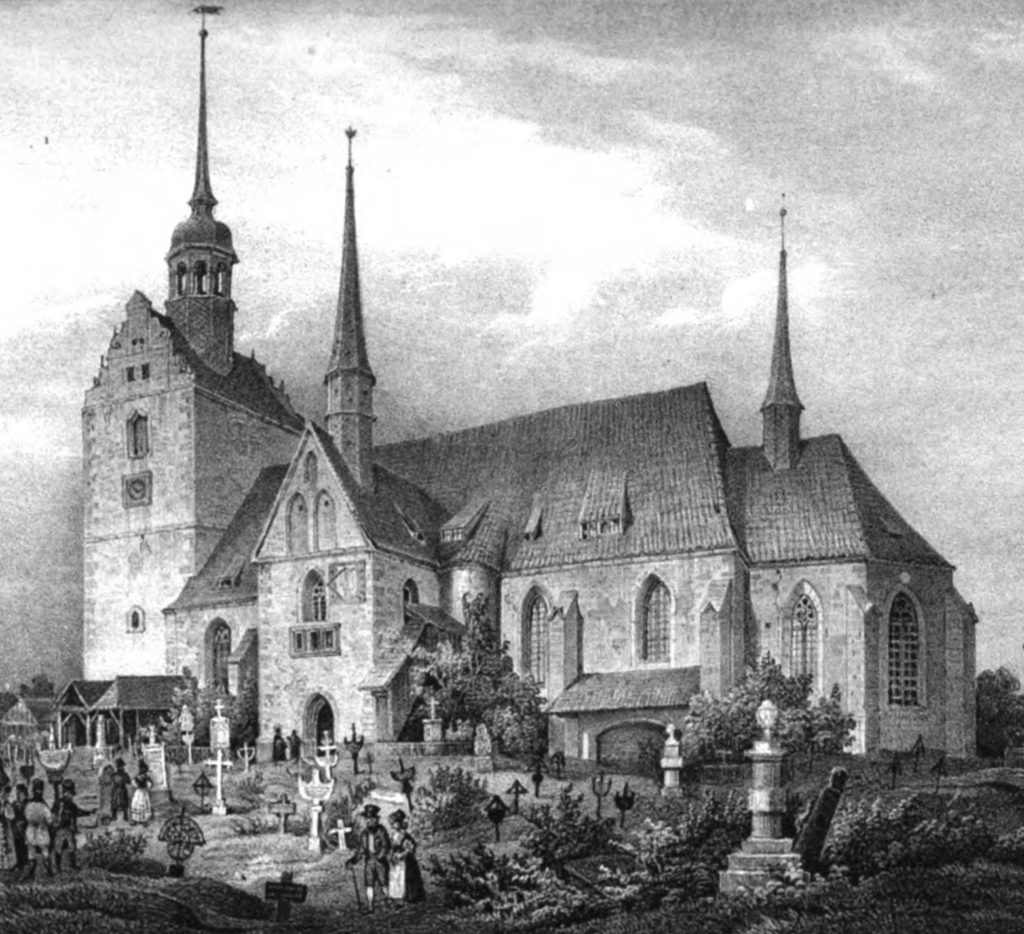

At a bend in a rutted road that headed north out of Dresden lay the small village of Lausa. The surrounding landscape was farmland and forest, with a small stream that lazily trickled through the area and fed its ponds. It was eight miles north of the provincial capital city, and it hosted a modest Lutheran church that served the small surrounding villages.

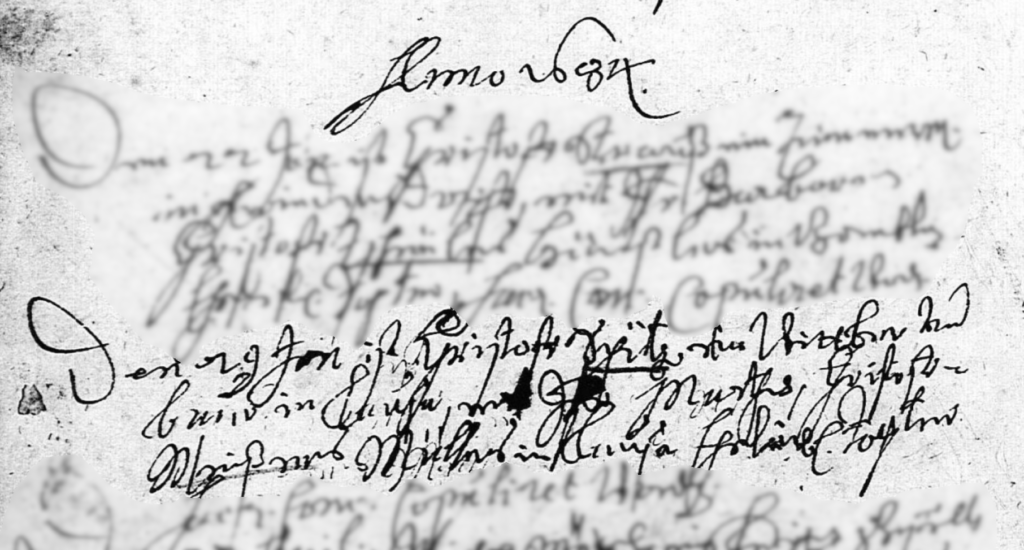

It was in this area in 1659, in Hermsdorf to be precise, that Christoph Schütze was born to a farm laborer.[1] And it was in the parish church of Lausa in 1684 that Christoph married Martha Meißner, daughter of a miller in Lausa, while he was engaged in farming the acres surrounding the town.

The area of Lausa was a kind of hothouse for Schütze families.[2] The parish church register of 1717 to 1756 shows that one of every six children baptized during that period was named Schütze,[3] a fairly remarkable number.

It is Lausa, then, which we consider to be the origin of our modern-day Schütze family line — where Christoph and Martha began a string of descendants that stretches today as far away as North America.

Farmers, merchants, and craftsmen

One of the fruits of their union was a son, George (1684-1759), who, like his father, was also a farmer in Lausa.

George married Elizabeth Neumann in 1711, and they had a son, Christoph (1719-1769), who became a flour merchant (Mehlhändler) in the adjacent village of Friedersdorf.

Christoph, in turn, wed Rosina Leuthold (remember that name) in 1742 and from their marriage came Johann George Schütze (1750-1799), who started as a flour merchant and later became a canvas merchant (Leinwandhändler) in Friedersdorf.

Johann George Schütze in turn married Hanna Sophia Menzel in Lausa in 1775, and their first child was Johann Gottfried Schütze (1777-1837), who worked as a canvas merchant, linen weaver (Leinenweber) and a barrel maker (Böttcher) in Lausa, Grünberg, and Friedersdorf.

Gottfried (Germans frequently went by the last of their forenames) had wandering feet — and a wandering eye, which got him into trouble. However, we owe a change of scene to him.

Our cousin Hugh asked me if I’d found any heroes or villains in my Schütze family research. I’d have to say that Gottfried may have come close to being one of the latter.

At the age of 23, Gottfried married Johanna Christiana Leuthold, his 19-year-old second cousin, in Lausa. (In his defense, small villages don’t have large gene pools.) Their first child was born eight months later, followed by four additional children born in Grünberg and Friedersdorf between 1801 and 1809. Despite their many children, the cooper and his wife ended their marriage in divorce . In the midst of the divorce a married woman, Anne Rosine Hauptmann, caught Gottfried’s eye, and they had an illegitimate daughter, Anne Christiane, who was born in 1815. Gottfried, being the upstanding man that he was, abandoned both mother and child, and the daughter was raised by her mother and her cuckolded husband.[4]

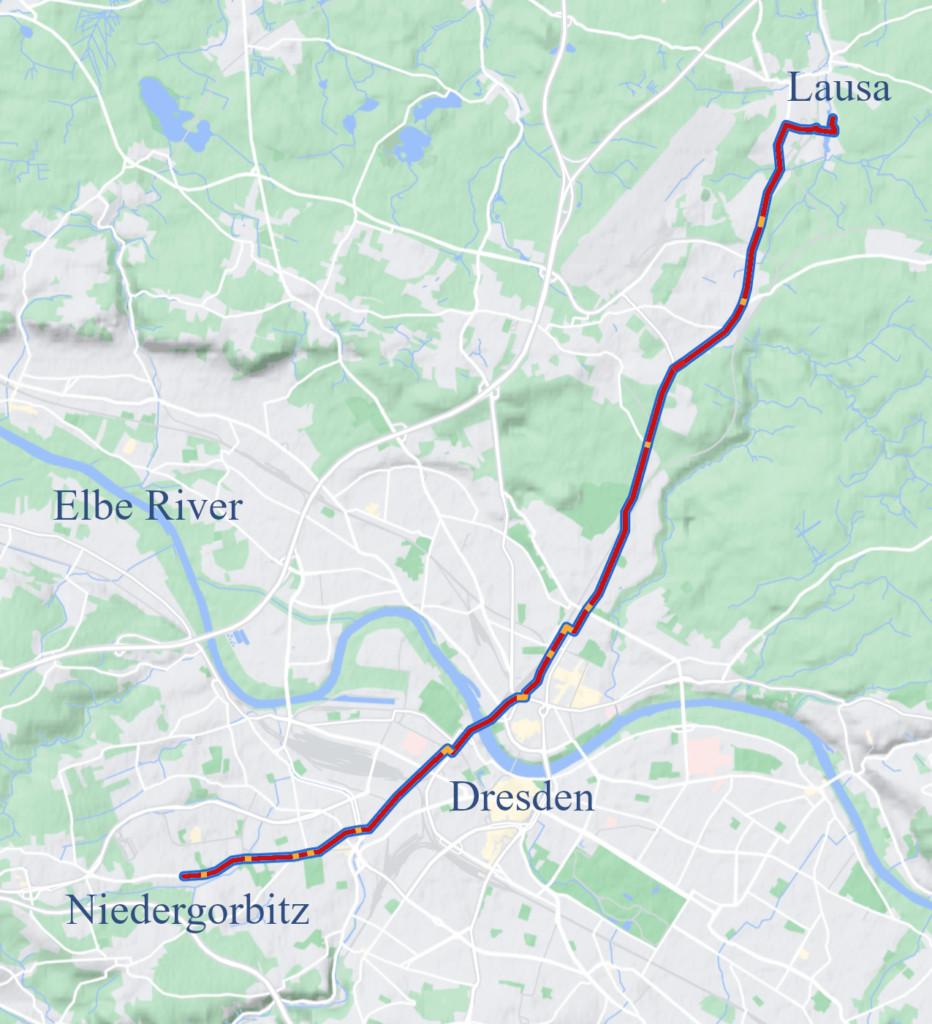

Meanwhile, Gottfried — who by the way was our great-great-great-grandfather, though maybe not as great as the title implies — relocated to the other side of the Elbe River, southwest of Dresden, to the village of Niedergorbitz. Whether he moved there by choice or force isn’t known — that is, we don’t know whether his path was lit by his own torch or that of pursuers.

Life south of the Elbe

Once Gottfried was across the Elbe, a young widow caught his attention and he married Johanna Christiana (née Barthin) Berndt in 1820 at the parish church in Briesnitz. Christiana, the daughter of a cattle farmer (Viehpächter), was a woman who’d had some hard knocks in life, namely, losing a husband to fever and one of their two sons at birth. She was also apparently a stabilizing (after all, her father raised cattle … stable … oh, forget it) force in Gottfried’s life. As Gottfried continued his barrel-making career in Neidergorbitz, the couple raised the son from her first marriage and added five children of their own.

Gottfried passed away at the age of 59 of emaciation (Auszehrung), likely caused by tuberculosis, diabetes, or cancer. Christiana followed him to the grave 15 years later at the age of 62.

Friedrich August Schütze

The eldest of Gottfried and Christiana’s children was Friedrich August Schütze (1821-1870). August was born at five in the morning on Christmas Eve of 1821 in Niedergorbitz. It may well have been a snowy morning in that part of the world, and little August may have been welcomed as an early Christmas present for the newly married couple.

Christmas Eve was a special time for our family when I was growing up. My parents, siblings, aunts, uncles, and cousins gathered at our grandparents’ house in Detroit to share a meal, play with cousins, and open gifts by the Christmas tree. Now that we know that our grandfather’s own grandfather was born on Christmas Eve exactly two hundred years ago, it will give us another reason to celebrate.

The Coal Mines

Young men looking for work typically gravitate to the leading industry of the area, and for the towns south of Dresden that industry was coal mining, which came into full bloom in the coal-rich hills of the Döhlen Basin around the same time that August was born. His older half-brother, Gottlob Berndt, became a miner in the town of Großburgk[5] and he may have been the one to convince August to join a mining crew there when he was of age, likely around the time of his father’s death when August was 15.

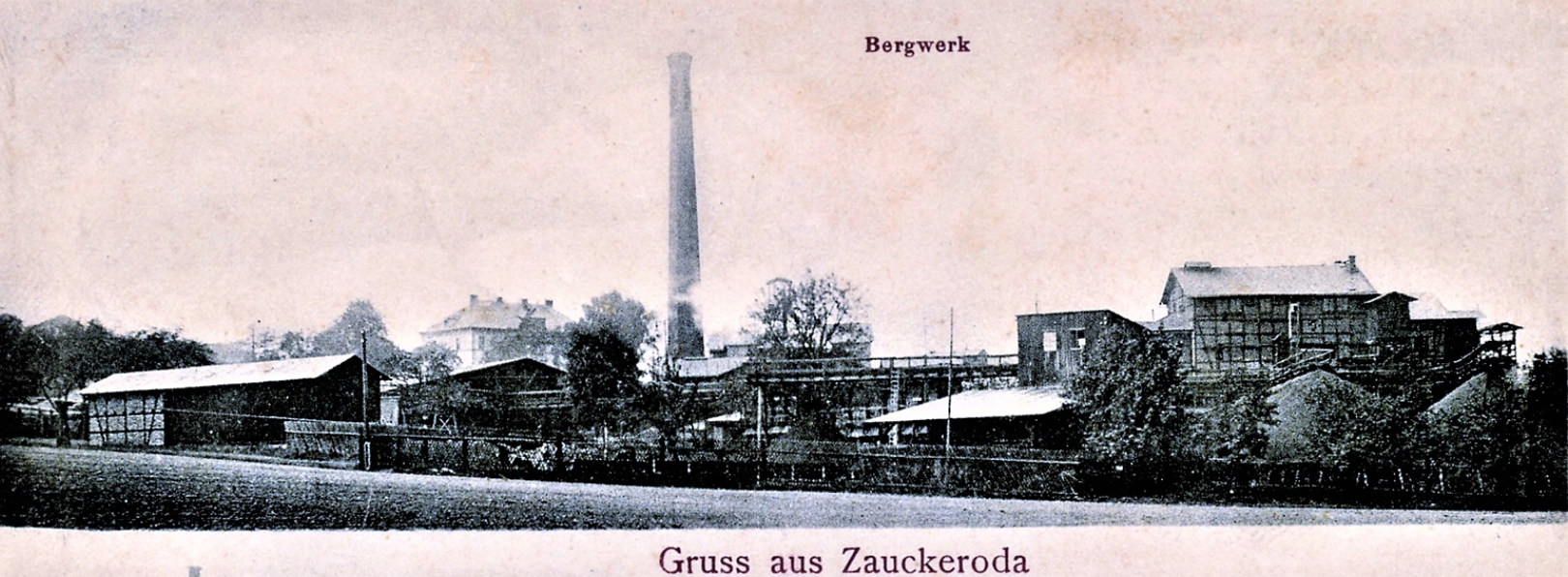

Perhaps supporting his mother and siblings for a few years, August eventually moved from Niedergorbitz to the mining town of Zackerode three miles to the southwest. It was here he met a young widow who, like his mother, lost her husband early in her first marriage.

The widow, Hanne Sophie (née Lehmann) Rothe, was born in Zauckerode in 1823 to a coal miner (Kohlenhauer)/mine carpenter (Bergzimmerling). Her father died at age 48 in 1841. Two weeks later Sophie, then 18, married a coal miner from Großburgk by whom she was pregnant. Five months later she gave birth to their son, but the child died a few months afterwards from a tumor.

Sophie then gave birth to twins in 1843; one died at birth, the other died two days later. As if that wasn’t enough, her husband passed away in 1845 of weak nerves (Nervenschwäche), less than four years into their marriage. All of this occurred to her by age 22.

In 1848 Sophie married our great-great-grandfather Friedrich August Schütze at the area’s parish church in Pesterwitz. The couple had eight children between 1849 and 1863. The oldest was their son Ernst Gustav. Our great-grandfather Friedrich Hermann was second, born in 1851.

An excellent website, mindat.org’s “Freital, Sächsiche Schweiz-Osterzgebirge, Saxony, Germany,” helps to visualize the towns and mines around Zauckerode and Großburgk, showing a number of postcard views dating to the early 1900s. Although that would be a few decades after the era of our family’s story, it gives an idea of the landscape against which the drama of our ancestors’ lives played out.

Life at home would have been busy for Sophie, nurturing and tending to the needs of her children. Though she lost two of her three daughters at young ages, she had six children remaining at home.

Likewise, life in the mines for August was strenuous. He worked for the Freiherrlich von Burgker Steinkohlen-und Eisenhüttenwerke mining company in Großburgk. There were a number of mines in the area,[6] and we don’t know in which one, or ones, he worked. Whichever it was, he would have come home after a day or night underground exhausted, sweaty, and covered in coal dust.

“… a skilled worker breaks five to six tons of coal during an eight-hour shift.

“… a skilled worker breaks five to six tons of coal during an eight-hour shift.

“…his main instrument is the wedge pick. With this he first made a horizontal incision one and a half cubit deep under the coal to be mined, the scrape. An iron drill is then used to dig a hole thirty-six inches deep and three-quarters of an inch wide, in which the twelve-inch-long powder cartridge, speared onto the ignition needle, an iron rod, comes to lie. At the top you ram the borehole with a solid mass, “occupy” it, as the word is. The ignition needle is then withdrawn from the cartridge and the trimmings and the ignition channel is obtained in this way. Finally, a rocket causes the explosion, which blasts the coal blocks off the wall.”[7]

Trail’s End

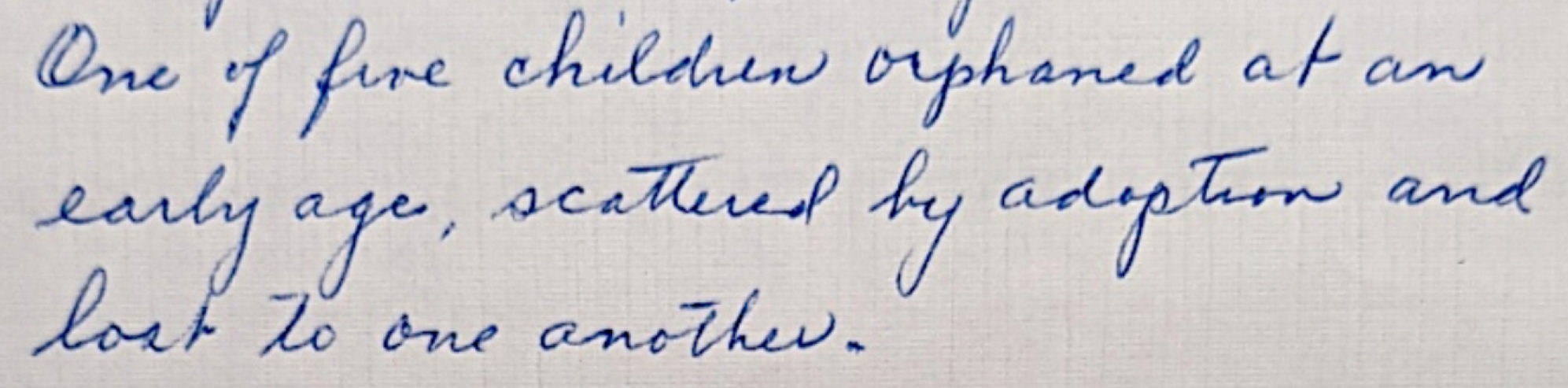

August’s granddaughter, Harriet (née Schutze) Davis-Ray left a note about her father Hermann’s childhood which read that he, August’s second child, was:

The note is telling in a couple of ways. First, it only mentions five of the six surviving children in the family. That’s because, unfortunately, the oldest son, Gustav, committed suicide shortly after his mother’s death.

The note also indicates that Sophie and August died early, which church records confirm. Sophie died in 1868 at age 45 of a stroke or cerebral hemorrhage (Schlagfluß). Her eldest son, as mentioned, died later that year, and her surviving children ranged in age from 5 to 17.

August apparently met his death in the mines, dying two years later at age 48 in March of 1870 from an accident (Verunglückte). Mining was a dangerous career, as evidenced by the loss of 276 miners the previous summer in an explosion in two of the Großburgk mines.

With August’s death we come to the end of the trail of our German ancestors. His eldest surviving son Hermann, of course, left the Dresden area to pursue a career as a butcher in Hamburg, and later emigrated to the United States. But it was the Schütze families in Lausa, Friedersdorf, Niedergorbitz, and Zauckerode in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries who set the story in motion and whom we can credit for seeding the generations that followed.

Regarding Hugh’s question of villains and heroes, I’d be tempted to say that August may come close to being a stoic hero, a common man who worked laboriously to support his family, and who had to deal with the grief of his wife’s and eldest son’s passing before his own tragic demise.

Notes:

1. Records are increasingly illegible — between poor handwriting and poor paper — the farther back we go. Plus the Lausa parish records begin in 1644, so we can’t go back farther than Christoph.

2. A graphic representation of the distribution of current-day Schütze families in Germany shows that this area still has a strong family presence. See https://www.namenforschung.net/fileadmin/dfd/maps/Schütze.pdf.

3. In the baptismal register there were 979 baptisms registered, of which 143 had the surname of Schütze, which calculates to 15%.

4. Evidenced by Anne Christiane Schütze’s death register. She died of fever in Lausa at age 17.

5. Gottlob Berndt’s occupation at the time of his marriage in 1839 was a miner (Bergarbeiter) and he lived in Großburgk.

6. A drawing of the area’s numerous mines is at Das Döhlener Becken bei Dresden, pages 331-332.

7. Hugo Scheube, “In the Grave of the Buried,” from an account of the mine explosion that killed 276 miners in Großburgk on 2 August 1869.

I have information of a Hermann Schutze who immigrated to the United States officially around 1890. Would love to find out more and see if it is the same person mentioned.

Mr. Schutze,

Please email me at schutze@cox.net and we can see if we have a common ancestor.

Thanks, Jamie

My great-grandfather was Ludwig Hermann Schütze (1869-1943), he left Berlin, Germany around 1890 to work in New York and later returned (married and with four children) around 1904. I did a little research, have fotos und stories. Contact me!