What’s in a name? That which we call a rose

What’s in a name? That which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet

‘Romeo and Juliet,’ William Shakespeare

This is the story of Rose Estall, our grandmother Bessie’s sister, who through some name changes left me at sea in the search for her. (Ironic, considering Bessie believed Rose was lost at sea.)

Click on image to expand

Click to expand

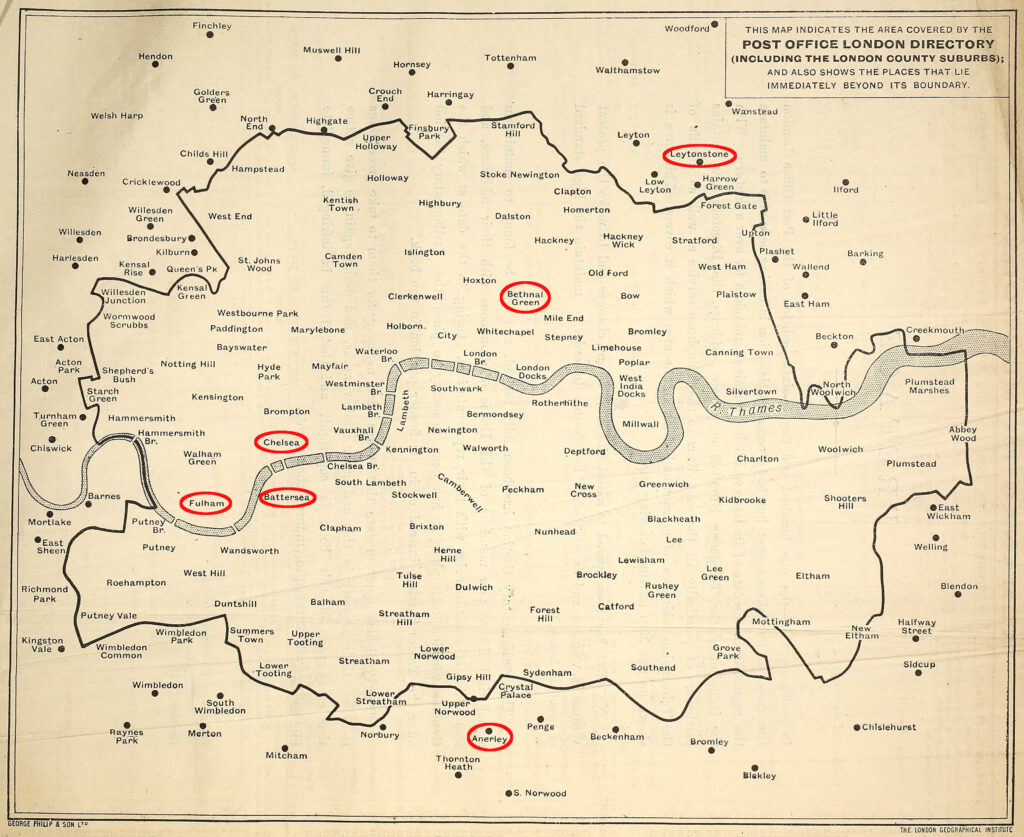

Rose Estall was born on October 21, 1895, in the Bethnal Green Workhouse infirmary. She was the third to last of Sarah (nèe Hutchings) Estall’s eight children. Her mother, a seamstress, had three children with unnamed fathers before meeting Rose’s dad, possibly indicating she used prostitution to make ends meet. Her father William Edward Estall, a dock worker and general labourer, had two children out of wedlock before meeting and marrying her mother. Unfortunately, neither parent was a long-term fixture in young Rosie’s life.

Her older sisters — Bessie, four years her senior, and Lily two years — walked her from the age of two to the neighborhood Globe Road[1] primary school. Their home was in the multi-building, multi-story tenement of Quinn’s Square – a complex that a police inspector at the time referred to as “there are no worse places to be found.”[2]

When Rose was four her mother passed away from acute meningitis. Her father, oftentimes sickly, entered the Bethnal Green Workhouse infirmary shortly thereafter, bringing the children with him. This would begin Rose’s upbringing at the hands of the London Workhouse resident school system. She spent a year at Bethnal Green’s Leytonstone School with her half-brother Tom and sister Lily. (Bessie was confined to the infirmary.)

Upon her father’s recovery and discharge from the workhouse he promptly abandoned the kids with his former mistress’s father in Syndenham … who immediately turned the kids over to the Lewisham Workhouse.

Fortunately for Rosie — age five at the time — her older half-brother Thomas and her sisters Bessie and Lily were also admitted to the Workhouse and sent to its Anerley School with her. Thomas, at age 12, was then sent off to the Exmouth Training Ship on the Thames. The sisters remained together at Anerley for the next five years.

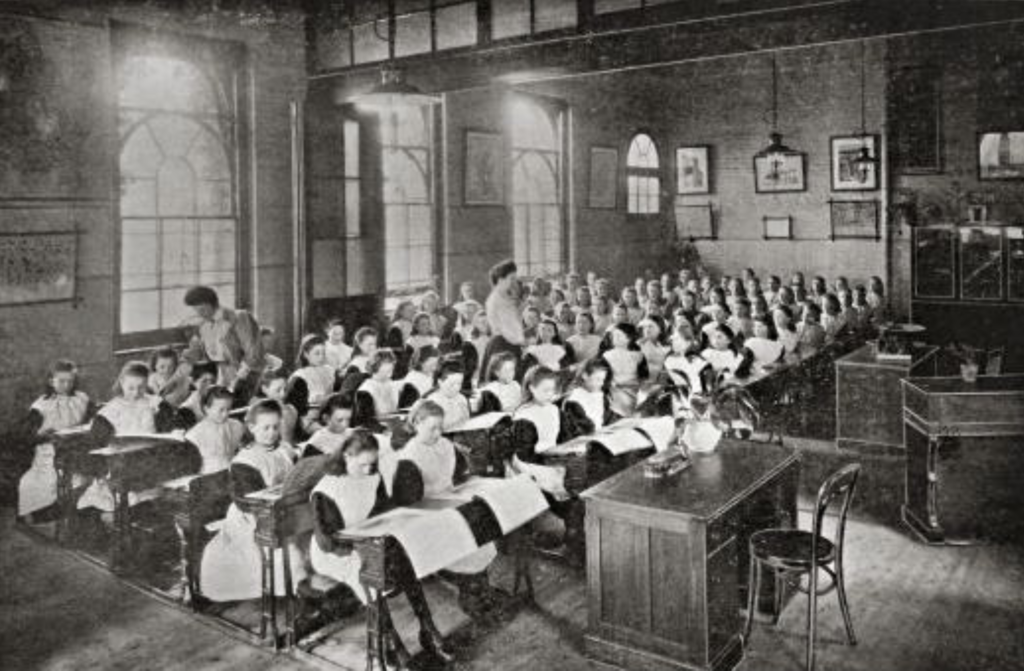

Click on image to expand it in new tab

According to the recollection of Lily, Rose’s sister, the school uniform was a blue serge with a white smock apron and lace collar. On Sundays they wore maroon serge and a straw hat for church and were given a straw mat for kneeling during services. They loved the organ music; Lily recalled that Rose was a good singer.

The dorms held around 500 girls and an equal number of boys, housed according to gender and age. Meals were sparse and regimented, with no talking allowed. Breakfast was a slice of bread and cocoa. The evening meal was a slice of bread and skim milk (and jam when outside visitors were present, for show). The mid-day meal varied by day: Monday was plum pudding; Tuesday a meat pie; Wednesday cold meat; Thursday pea soup; Friday cold meat; Saturday suet pudding; and Sunday a meat dish. Only when outside visitors were present were second helpings available at the end of the table.

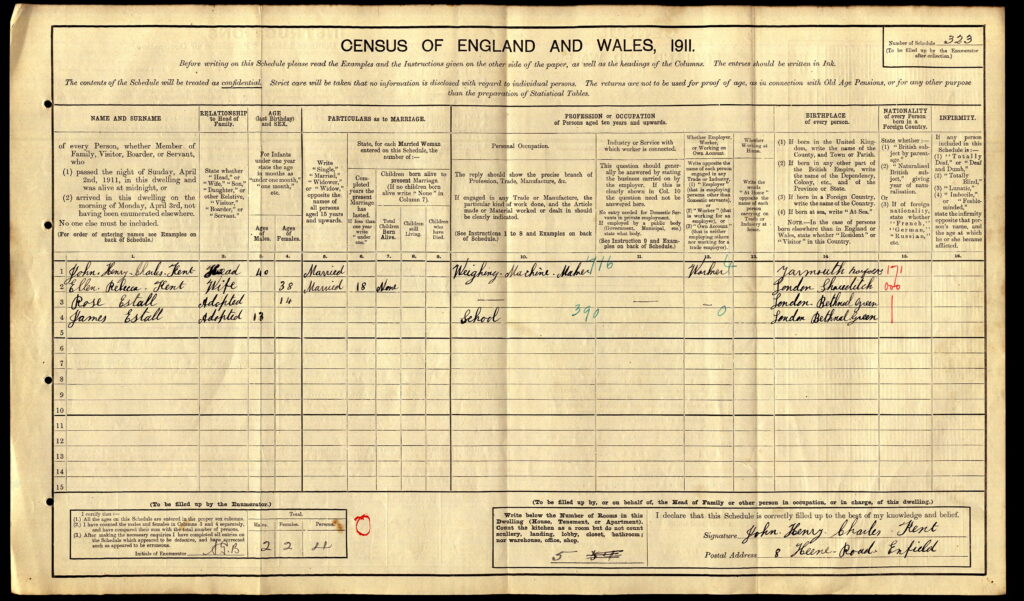

In March of 1906 the girls’ father, William Estall, who’d abandoned them and moved back to Bethnal Green, passed away, leaving the children now both deserted and orphaned. They volunteered to emigrate to Canada through the Home Children program administered by Annie Macpherson. At the end of May they were released from Anerley to the Macpherson Home of Industry in South Hackney to prepare for the trip. Rose, only ten years old at the time, was a bed wetter, and her sisters took her to bed with them in hopes of curing that condition,[3] but it didn’t work. Rosie was deemed unfit for emigration and sent back to Lewisham when her sisters left for Canada in July.

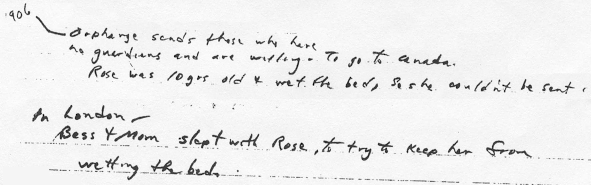

Click on image to expand it in new tab

The Lewishham Workhouse sent Rosie to a scattered home on Gilmore Road. Scattered homes were run by foster families and were designed to integrate groups of orphaned or abandoned children into neighborhood schools rather than placing them in isolated cottage homes or in workhouse schools. Rose only lasted there a year (for a reason that wasn’t documented) and was readmitted to the workhouse’s Anerley school for the next two years. She was finally discharged in 1909 at age fourteen, possibly to the care of James and Ellen Kent, who’d adopted Rose’s younger brother Jim at age two.

A year later her half-brother Thomas committed suicide while serving with the English Army in Cairo, Egypt. Rose was noted as his nearest next of kin.

In 1911 Rose, then 15 years old, showed up in the census as adopted and living in Enfield with the Kents and her brother.

Click on image to expand it

From Canada, Bessie and Lily exchanged letters with Rose. Rose indicated that she was planning to get married and she hoped to travel to North America to join her sisters.[4] Apparently the correspondence ended when the Estall sisters left Canada for California in 1911. As mentioned before, Bessie believed that Rosie was lost at sea on her way to North America.

Click on image to expand it in new tab

For me, Rosie’s paper trail went cold after the 1911 census. I spent years unsuccessfully searching ship passenger lists, marriage records, death records, workhouse registers, and censuses to track her down. She was a mystery that I couldn’t solve … yet couldn’t give up on.

Rose is a rose is a rose

Rose is a rose is a rose

‘Sacred Emily,’ Gertrude Stein

And then in the spring of this year I serendipitously found her in a family tree on Ancestry.com. The tree was put together by a previously unknown third cousin of ours – our common ancestor being Rose’s paternal grandfather – and over the ensuing weeks our cousin uncovered “the rest of the story” of Rose Estall: from motherhood to the grave.

Click on image to expand it

Rose’s story picked up again in 1915 in the west London districts of Chelsea and Fulham. In July of that year she entered the Chelsea Workhouse infirmary to give birth to an illegitimate son whom she named Thomas James Estelle, perhaps in honor of her older brother Thomas and younger one James. Rose was 20 and working as a domestic servant in Fulham. When she left the infirmary at the end of September she did so without Thomas in hand; he was left to be adopted out.

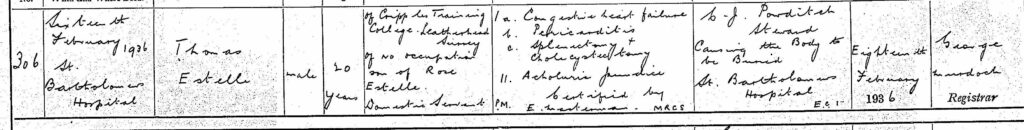

The 1921 census shows that Thomas was adopted by the boot maker and auxiliary postman Edward Clark and his wife Florence of the north London district of Edmonton, a couple who in 1921 were ages 48 and 43 respectively and had two older children of their own. Thomas was four at the time of the census. Although he’d found a home and family, Thomas had a short, difficult life, dying at the age of 21 (the same age as the uncle he’d likely been named after). He’d been admitted to the Cripples’ Training College to learn a trade compatible with his handicap but he died shortly thereafter in 1936 of congestive heart failure.

Click on image to open in new tab

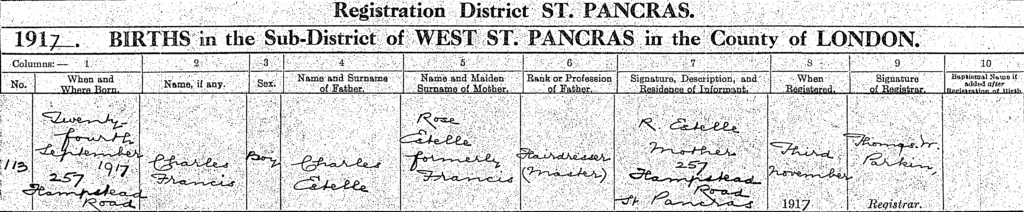

Meanwhile, Rose had a second son, Charles Francis Estelle, in September of 1917. The birth certificate lists Rose as “Rose Estelle formerly Francis,” living on Hampstead Road in the St. Pancras district, and lists the father as Charles Estelle, a master hairdresser. There is no previous record of their marriage, and there are no obvious candidates for the father in other contemporary records — i.e., censuses, voter registers, directories, vital records, etc. Although one could accept his identity at face value, there are alternative explanations which we’ll come to in a bit.

Click on image to open in new tab

The young Rose, now with the son she kept, was living hand-to-mouth in Fulham. She literally sang for her supper, according to a recollection of her son. “He could remember queueing up for stale bread when he was young. Prior to that, he remembered his Mum holding him in her arms when he was very young, while she sang in the street for her supper.” [5] Interestingly enough, Rose’s sister Lily remembered that Rose had a good singing voice while at Anerley.

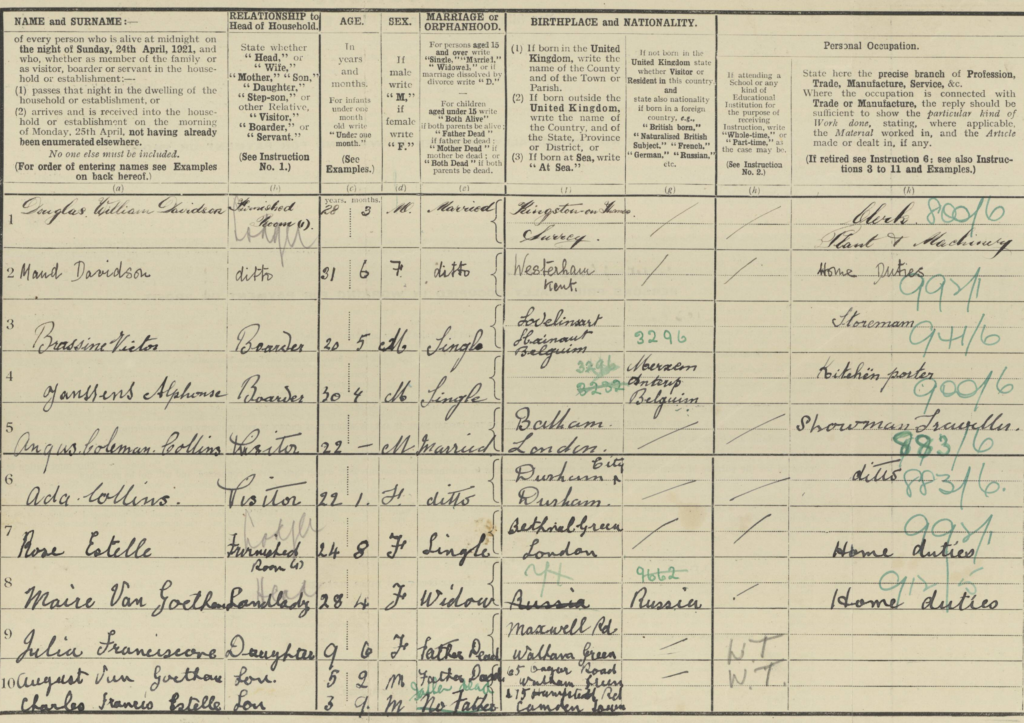

The 1921 census provides a fascinating snapshot of Rose, who was 24 years old at the time. It shows her as Rose Estelle, single [as opposed to married or widowed] with an unpaid[6] occupation of “home duties,” living in a furnished room in the widowed Marie Van Goethem household. Rose’s son Charles, at 3 years old, is listed four lines down as having “no father.” His position on the page, following Marie Van Goethem’s two children, seems odd but may not warrant reading anything into. By inference one assumes that Rose is helping Marie with household duties and helping raise the children. Whether the relationship with Marie was strictly transactional or based on friendship is unclear. There are, however, some indications it was likely the latter.

Click on image to open complete PDF in new tab

Digging deeper into the census, we see that one of Marie’s children is Julia Franciscone. Julia’s father was Eduardo Franciscone,[7] a hairdresser’s assistant in Fulham, associated with a family operating a hairdressing shop on Waterford Street.

Marie had what we could call a “history” with the apparently volatile Franciscone family. In addition to having a daughter by one of them in 1911, she had a run in with another of them in 1923 over money he owed her. This was with Celestino Vincenzo Franciscone, aka Charles V. Francis, a resident Italian hairdresser who a few years previously was warned off with a gunshot after insulting an acquaintance’s wife (it would be interesting to learn just what the nature of the “insult” was).[8] When Marie came to collect the money he owed her, they had some words, she picked up a stick and he in turn picked up a broom and he banged her on the head with it.[9]

Whether Marie herself was volatile, or whether the broomstick did some damage (she showed up in court with her head swathed in bandages), Marie ended her days in a mental hospital. Nevertheless, these instances of violence and strife might well reflect some instability in the fatherless household, or more generally the chaos frequently found under poor economic living conditions.

Even more interesting, it seems that Rose herself had a history with Celestino Vincenzo Franciscone. Given that Celestino also went by the anglicized name Charles V. Francis,[10] it is more than a curious coincidence that when her second son was born in 1917 she said her former surname was Francis,[11] that the child’s father was a hairdresser, and she named the son Charles Francis Estelle.

Furthermore, Rose’s granddaughter relayed that “I remember my Dad saying that his father’s name would have been pronounced ‘Cileste’ or ‘Cilesto’ but I think he thought that his next name (which he would have thought was his middle name) was ‘Francesco.‘” She went on to write “I remember my Dad saying that there would have been a proper way to pronounce the ‘Francisco’ name and then said that the Estelle name would have been pronounced Estellè (with an accent because of the ‘Italian’ connection – evidently the story told to him by his Mum).”[12]

It seems pretty clear that Rose believed Celestino was Charles’s father, or alternatively, was looking for someone to pin the Rose on, so to speak. However, Charles’s daughter’s DNA doesn’t show any Italian heritage[13] so Rose apparently guessed wrong as to which lover fathered her son. Celestino went on to marry another woman in 1923.

Nobody knows this little Rose

Nobody knows this little Rose

‘Nobody Knows This Little Rose,’ Emily Dickinson

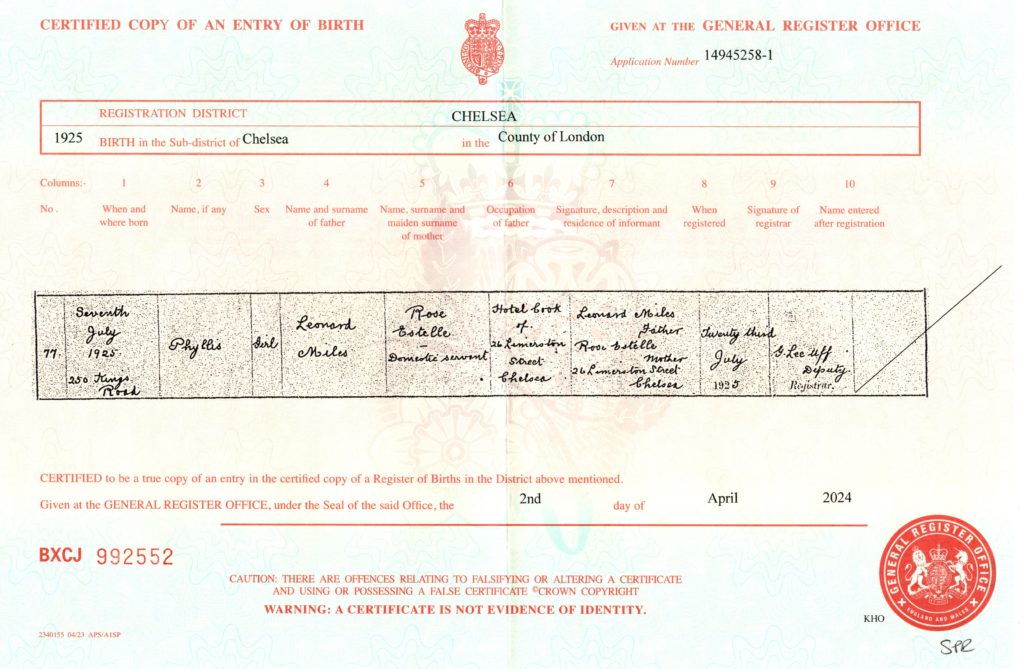

Rose next surfaces in 1925 when she gave birth to her daughter Phyllis at the Chelsea Workhouse infirmary.[14] On the birth certificate she identifies herself as Rose Estelle, a domestic servant. The father is identified as Leonard Miles, a hotel cook. They are living together under separate surnames on Limerston Street in Chelsea. Yet again, Leonard is as elusive as Rose’s former partners: there are no corroborating documents showing his residence, their marriage (though Rose later maintained she was a widow of his), nor his death. Nevertheless, Rose adopted the surname Miles for the balance of her life.

Click on image to open larger image in new tab

Click on image to open

Rose, a single mother of limited income, sent her son Charles off to Bisley School[15] in Surrey, which operated as a resident school for homeless or destitute boys. She also sent her daughter Phyllis off to school, though which one is open to speculation, with some of the family thinking that it was a private school with tuition paid by Rose’s employer,[16] and others thinking a Workhouse district school was more likely.[17] Regardless, there was a pattern to Rose’s parenting: her children were sent off for adoption or to resident schools. This perhaps reflected the hard life choices of a young, single, working woman struggling financially. She may also have borne in mind that she had been raised in the workhouse school system with no apparent harm.

Rose, however, didn’t abandon her two younger children. She still played a part in their early and later lives.

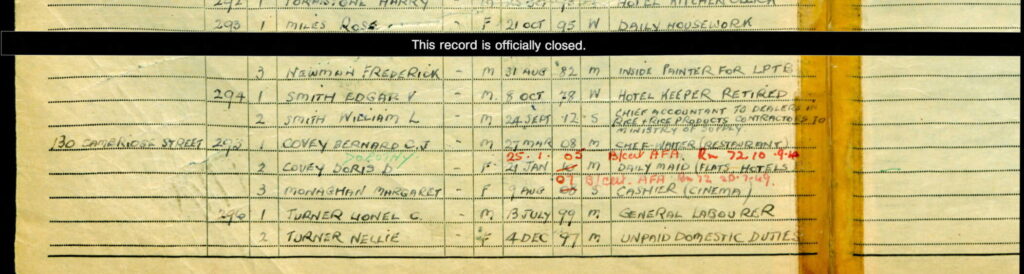

In 1939 England conducted a register of its inhabitants to support the production of national identity cards. Rose Estall, now Rose Miles, showed up on Sussex Street in Westminster, adjacent to Chelsea, as a ‘widow’ engaged in ‘daily housework.’ It is her birth date on the form that confirms Rose Miles, formerly Rose Francis, was indeed Rose Estall: it shows she was born on 21 October 1895. The earlier census of 1921 showed she was born in Bethnal Green. Between the two censuses we have confirmation of her identity.

Click on image to open larger image in new tab

Rose’s experience with privation undoubtedly extended into the era of the Second World War, when rationing hit the London civilian population and certain goods and foodstuffs were hard to find.

Click on image to open

Along with the economic stress, Rose’s son Charles served on a corvette in World War II, a ship designed for anti-submarine warfare to protect the north Atlantic shipping routes. He took some shrapnel in his hand, which fortunately didn’t do lasting harm, but having a child in harm’s way is particularly hard on a mother.

And of course Rose would also have shared in the anxiety and terror of neighbors who hurriedly sought shelter at the sounds of air raid sirens, the rumble of engines of German bomber airplanes overhead, and the whistles of German V-1 and V-2 rockets. An estimated 18,688 civilians in London were killed during the war and 1.5 million were made homeless.

The fires, the fear, the hunger, the rubbled neighborhood streets, the losses . . . Rose lived through a good deal of difficulty at most every stage of life.

Click to open larger image in new tab

Rose in her last years worked as a cook at the Battersea Power Plant[18] across the river from her home on Uverdale Road in Chelsea.

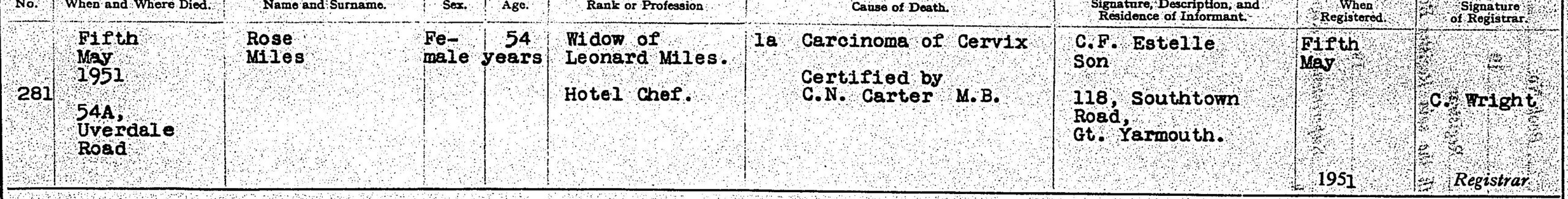

It was from the Chelsea home that Rose passed away in 1951 at the age of 54 from cancer, namely cervical cancer. Her death certificate shows her as the widow of [the elusive] hotel chef Leonard Miles. Her son Charles, living in Great Yarmouth on the eastern coast, was listed as the one who reported her death.

Click on image to open larger image in new tab

Her body was buried in the Old Brompton Cemetery in Chelsea in a common grave. Being a common grave, there was no headstone to commemorate her life or her passing.[19]

So ended the story of my grandmother’s “missing” sister. She was raised in working class poverty and apparently spent much of her adulthood in the same. Her life was marked by childhood institutionalization, loss, abandonment, and instability. Like her mother, she had children by unknown fathers and was difficult to track due to name changes. But also like her mother, she gave life to the next generation and showed genuine concern for them.

I know our grandmother would have been happy to know that Rosie wasn’t lost at sea. Decades later, we have some resolution on the mystery of what happened to her. It even feels like we have some reconnection — unfortunately posthumously — but if there is an afterlife, we can now envision the sisters sitting together again, holding hands, and reminiscing about their years at Anerley … and catching up on “the rest of their stories.”

‘A word with you, that of the singer recalling—

‘A word with you, that of the singer recalling—

Old Herrick: a saying that every maid knows is

A flower unplucked is but left to the falling,

And nothing is gained by not gathering roses.’

‘Asking for Roses,’ Robert Frost

AFTERWORD

This story of Rose Estall wouldn’t have been possible without the generous contributions of cousins who live in England and Wales, whose names I’ve omitted out of privacy concerns. This story really does end in reconnection … not just the figurative one between the Estall sisters, but the literal ones among the Estall descendants.

DNA is a fairly new addition to the field of genealogy and one I wasn’t very familiar with. But DNA matches among myself and these cousins has proven our mutual connections to the Estall family. DNA evidence also eliminated a candidate for the father of one of Rose’s children, though we are still in the dark as to the fathers’ true identities. As more people take DNA tests and we find matches, we may eventually fill in more blanks in Rose’s story … and maybe in our own as well.

Endnotes

[1] Rosie was enrolled at the age of 2 years, 3 months. See Tower Hamlets: Globe Road School: Admission and Discharge Register for Infants, 31 Jan 1898.

[2] George H. Duckworth’s Notebook: Police and Publican. Charles Booth Notebook B350, page 39.

[3] Recollections of Lily Schrotzberger (née Susan Estall) as recorded by her son Ed. Copy provided to Jamie Schutze by JoAnn Schrotzberger.

[4] Recollections of Lily Schrotzberger.

[5] Email, F.T., 7 April 2024, Subj: Re: Rose Francis/Estelle/Miles. From one of Rose’s granddaughters.

[6] The green numeric code 992/1 translates to “Retired or not gainfully employed/not employed – unpaid domestic duties etc.”

[7] Birth certificate for Juiglietta Margherita Franciscone, born 23 Dec 1911 on Maxwell Rd, Fulham.

[8] “The Fulham Shooting Affray,” The West London Observer, 14 Nov 1919, p8.

[9] “Alleged Assault with a Broom,” The West London Observer, 13 July 1923, p3. Also: “Broom v. Stick,” The Kensington News & West London Times, 20 July 1923, p2.

[10] The 1939 England and Wales Register shows Franciscone, Vincenzo “known as” Francis, Charles V. employed as a Gentlemen’s Hairdresser on Avalon Road in Fulham.

[11] Marie, who’d had a child by Eduardo Franciscone in 1912 (with no apparent marriage), stated her surname as Francis when she married Theophile Van Goethem on 3 July 1915.

[12] Emails, F.T., 3 May and 10 April 2024, Subj: Re: Rose Francis/Estelle/Miles.

[13] Ibid.

[14] The place of birth is the address of the Chelsea Workhouse, which in 1925 was still in operation. The Chelsea Workhouse and Infirmary were turned over to the London County Council in 1930.

[15] Email, F.T., 8 April 2024, Subj: Re: Rose Francis/Estelle/Miles.

[16] Email, C.S., 3 April 2024, Re: Rosie Estall.

[17] Email, E.H., 12 April 2024, Subj: Re: Hello! Email from a great-granddaughter of Rose Estall.

[18] Email, F.T., 8 April 2024, Subj: Re: Rose Francis/Estelle/Miles.

[19] The Royal Parks, Brompton Cemetery, burial search for Rose Miles, 1951. The burial record shows she was buried in a common grave. According to Britain Express, “Brompton Cemetery, London,” https://www.britainexpress.com/London/brompton-cemetery.htm, “common graves saw up to 10 burials in a single deep grave, with no right to erect a headstone.”