“As soon as the incident is forgotten, so are you”

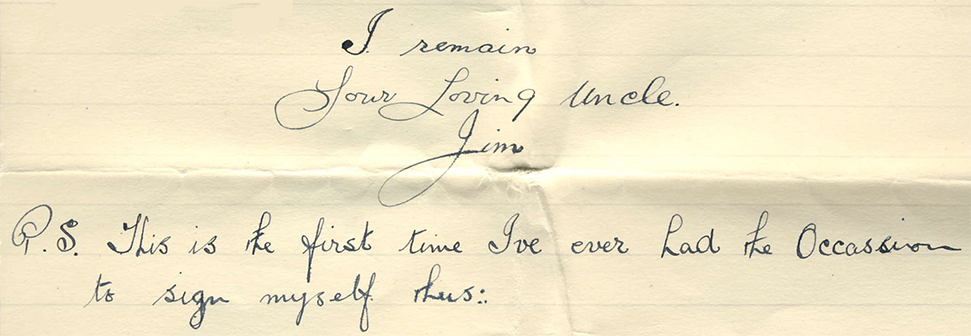

This line, written by my great-uncle Jim Estall to my father, was from a 1933 letter found among my dad’s mementos.

Prior to finding this letter I didn’t know about James Estall, my grandmother Bessie’s brother.

Bessie’s family broke apart after her mother died in 1899. James, her youngest brother, was adopted out in 1900 at the age of two when the rest of the family headed for the poorhouse.

Jim’s adoptive parents were a brass scale maker and his wife, John and Ellen Kent, from London’s East End. The family moved to Enfield, a small town north of London, and a decade later also adopted Jim’s sister Rosie after she was released from the poorhouse system as a teenager.

With good parents and now his sister in the fold, Jim’s life was looking pretty sunny as he headed into his teens. But war clouds were gathering. Clouds that, as it turned out, would darken the life of his generation over two successive wars.

The Great War.

Jim, who’d adopted his parents’ surname, was on the cusp of his 17th birthday when England declared war on Germany in August of 1914. As soon as he turned 18 he volunteered with the Royal Field Artillery and was sent to France. The National Roll of the Great War 1914-1918 summarized his four years of service thusly:

Shiny medals are nice, but Jim found they turn dull when the country recovers from war and gets on with life. As he indicated, once the battles are forgotten, so are the veterans. Jim was relatively lucky — he was among the 1.6 million British soldiers injured rather than among the 750,000 who died. But he developed a jaded outlook which he shared with his nephew while trying to dissuade him from joining the military service in America.

Two years after his return from war, at the age of 24, Jim married sweet Rosetta “Rose” Webb. Their wedding photo looks prototypical British, the ladies posing in their bonnets and the gentlemen in their vested suits and starched collars. Most of the guests were from Rose’s family, as Jim didn’t have any of his own.

Jim wrote that Queen Elizabeth I regarded the area around Enfield as a ‘happy hunting ground’ and that one of her palaces was in the centre of the town. He explained, tongue in cheek, that his wife Rose, a town native, “was not connected with Queen Elizabeth, although perhaps some of her relations may at some time [have] done a bit of washing for her.”

Jim was a motor driver, “a position that makes me travel the country,” which he used to advantage by visiting historical sites, particularly those associated with great English authors like Shakespeare and Milton. [This makes me, an English Lit grad, appreciate Jim all the more.]

He seemed to have a sunny outlook, as his wife wrote that “if he wasn’t laughing or passing some joke, I should think he were ill.” Together they raised two sons, Jimmy and Jeff, born in 1922 and 1930 respectively.

The 1939 England Register lists him as an “undertaker’s chauffeur,” which probably kept him closer to home so he could spend more time with the boys. But the man who helped transport the dead to their graves was to suffer another war-time loss of his own.

The Second World War

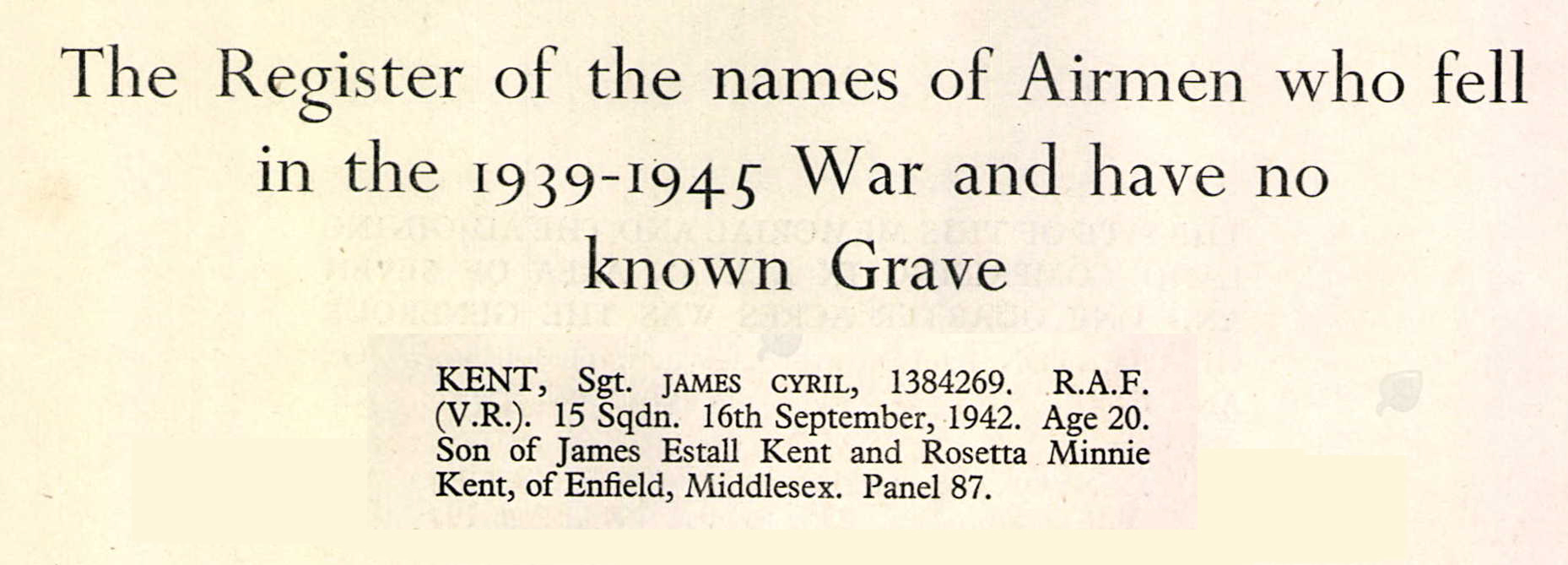

His older son Jimmy, like his dad before him, volunteered for service when the country went to war and he came of age, this time during World War II. Jimmy joined the Royal Air Force, the group that Churchill famously referred to in a 1940 speech: “never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.”

The personnel of No.15 Squadron in June 1942. Jimmy was undoubtedly among those pictured.

Jimmy was with the 15th Squadron, a heavy bomber unit which delivered their loads over the Axis powers on the continent. He went missing in September of 1942, and his dad unfortunately never even had the opportunity of transporting and burying his own son.

Jim treasured his long-lost family, proudly signing his letter to Leonard as “your loving uncle.” Of Jim’s two sisters in the United States, Bessie made initial contact by mail after WWI and Lily went to visit him in 1962 when they were both getting on in years. I can only imagine his happiness at the reunion.

And now, all these years later, we’re happy to meet him vicariously through his letter to my father.

Jim passed away in 1965. Rose followed in 1983.

Now, as we commemorate the 100th anniversary of the end of World War I — optimistically called the “war to end all wars” — we remember the sacrifices made by Jim’s generation…

…and of his advice regarding the glorification of war. “It’s all rot.”