The Estall family historians Mark and Kim Baldacchino have recently traced the Estall line a generation back from its first London appearance.1

The Baldacchinos believe William Estall, the tallow chandler of Whitechapel of the early 1700s (and our 6th-great-grandfather), was born in Lavendon, Buckinghamshire, a farming community sixty miles northwest of London, to William and Susanna (nee Valentine) Estall.

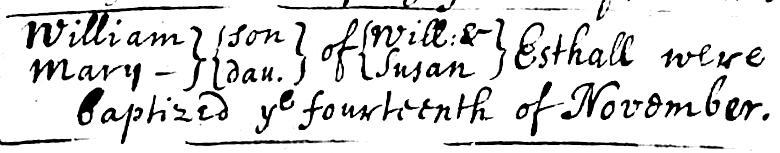

The junior William and his sister Mary were baptized in Lavendon in November of 1693, they being two of the five or six children in the family.2

Their father, William the Elder, was a farmer/yeoman in possession of horses, cows, sheep, and bees.3 He would have farmed the community’s common field, which wasn’t enclosed until 1801,4 in the company of his neighbors. The family worshiped, though perhaps only intermittently,5 at St. Michael’s church in Lavendon, a structure dating back to the early 11th century.6 In the 17th and 18th centuries the church was the site of several Estall baptisms, marriages, and funerals.

William the Elder, besides being a husbandman, also exercised his civic duty, appearing on a polling list — one of 25 men in Lavendon — voting for the Knights of the Shire in 1705.7 Exercising his social duty, he would have also had occasion to lift a pint or two at the thatch-roofed inn and pub, now called The Green Man, on Lavendon’s High Street. The pub still stands for anyone interested in rubbing elbows with Estall spirits of the past.

In the elder William’s will of 1740 he left most of his estate to his son George,8 likely indicating George was the eldest, hence in line for the lion’s share of the estate under the protocol of primogeniture.

The younger William received one shilling in his father’s will. Although measly, it wasn’t necessarily miserly on his father’s part, as explained below.

An Apprenticeship in London

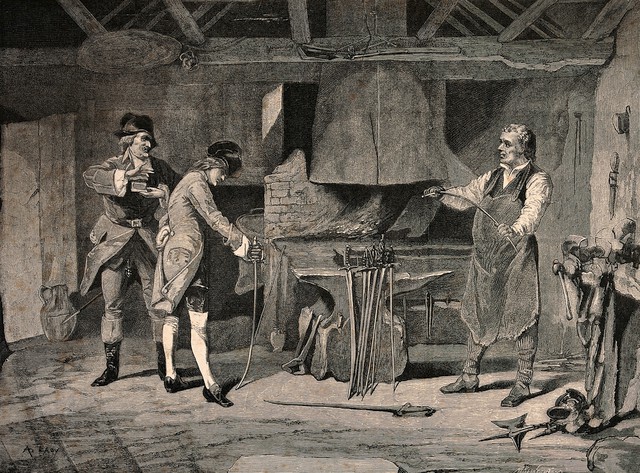

William the Younger left the farm and went to London in 1709 at around age sixteen to enter an apprenticeship in the Cutlers’ Company,9 a guild of metal workers making swords, knives, and domestic wares such as cutlery, razors and scissors.10 Apprenticeships were expensive, entailing years of training as well as room and board, often under the master’s roof.11 William’s father would have paid a considerable sum for this and would have felt justifiably relieved of further financial obligation, particularly since his son was then living in distant London.

An account of apprenticeship found in The Making of the English Middle Class: Business, Society and Family Life in London 1660-1730, provides an appreciation of the adjustment and hardship William endured in his teen years.

“It must have been a fairly traumatic experience for the young apprentice when, at the age of sixteen or so, he arrived with his box of clothes to start his term. For most young men, it was probably the first time they had been away from home and the first that they had seen of the basically hostile environment of the big city. Working conditions varied, but the hours were long, typically from seven in the morning to nine at night with a break of two hours for dinner at mid-day.”12

Apprenticeships typically lasted seven years, and shortly after William completed his (we assume he did, as marriage wasn’t allowed during apprenticeship13 and William married shortly after a typical term) he wed Hannah Skegg at St. James’s church in Clerkenwell, London, in January of 1717.14 It was a short-lived marriage, though, as Hannah passed away a little over a year later, in March of 1718.15 Given the timing of her death, it’s possible she died of complications from pregnancy or childbirth, considering the maternal mortality rate at the time was 10.5 for every 1,000 births.16

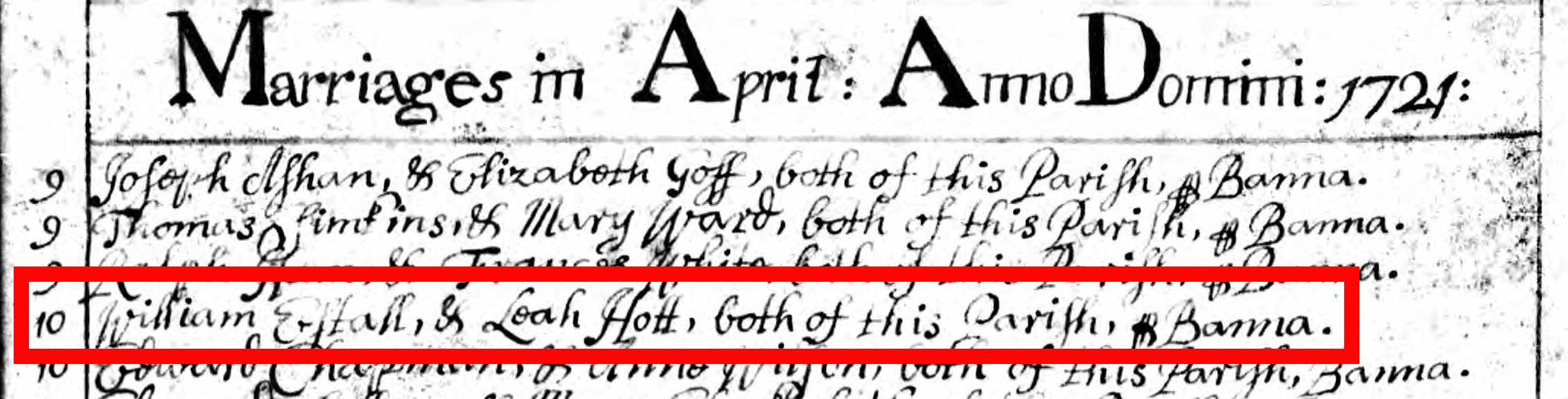

William then went through another transition. He moved from London’s north side to its east, marrying Leah Holt (or Hott, the marriage register writing is unclear) in 1721 while in his late twenties at St. Mary’s Church in Whitechapel.17

At some point he also changed careers. Considering the time and money invested in his apprenticeship, one may wonder why he would leave the cutlers trade behind. There are a couple of possible reasons.

When teenage sons were apprenticed it was typically the parents’ responsibility to “help them choose the particular career that they were to follow, ideally helping them discern their vocation.”18 As he matured, William may have discovered, however, that this wasn’t his natural vocation.

More likely, though, he left the trade because it was in the midst of relocating from London to Sheffield by the mid eighteenth century, where raw materials and water-power were more favorable for steel work.19

Whatever the reason for the switch, William took up the tallow chandler trade (making and selling candles made from animal fat) while raising a family in east London with his second wife Leah. The rest of his story is presented in the on-line book Footprints: The Immigrants, starting at page 89.

From farm to city

That, then, is the prequel, or back story, of the Estall family of London. Like so many of our ancestors, the family began on the farm and migrated to the city. The move by William Estall in 1709 from rural Lavendon (population around three hundred) to bustling London (population over half a million), and from working behind ploughshares to making swords (or perhaps steel utensils), makes this family, the Estall’s, among the earlier converts to urban life in our family’s history.

1. The Estall Family: A One-Name Study of the Estall Surname and Family Tree, https://estall.one-name.net/up/index.htm, accessed 15 March 2020.

2. The Centre for Buckinghamshire Studies, Buckinghamshire County Council, Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, England. A copy of William Estall’s will, obtained from the Centre, is in possession of this author.

A transcription of the will can be found at The Estall Family: A One-Name Study of the Estall Surname and Family Tree, “Wills: Will of William Estall died 1740,” https://estall.one-name.net/up/wills.htm, accessed 15 March 2020. In his will William Estall the Elder names five children and another son-in-law, bringing the count to three sons and three daughters. Only two of the daughters are identified by their forenames.

3. Ibid.

4. Gilbert Slater, The English Peasantry and the Enclosure of Common Fields (London: Archibald Constable & Co. Ltd., 1907), 271. Available on line at https://archive.org/details/englishpeasantry00slatuoft/page/n11/mode/2up/search/olney, accessed 17 March 2020.

5. Only three of their five or six children were baptized, and the wedding of William and Sarah (Valentine) Estall wasn’t recorded in the Lavendon or surrounding parishes’ registers.

6. British History Online, “Lavendon,” https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/bucks/vol2/pp161-165, accessed 17 March 2020.

7. Ancestry.com, “UK, Poll Books and Electoral Registers, 1538-1893, for William Eastall” [database on-line], image 47 of 237, accessed 4 Mar 2020.

8. The Centre for Buckinghamshire Studies, the will of William Estall.

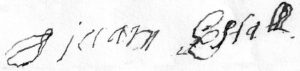

9. FindMyPast.com, London Apprentice Abstracts, 1442-1850, for William Astall. Details of the record transcription are: “Astall, William, son of William, Lavendon, Buckinghamshire, yeoman, to John Elton, 24 Feb 1708/9, Cutlers’ Company.”

10. The Worshipful Company of Cutlers, “History,” https://www.cutlerslondon.co.uk/company/history/, accessed 15 March 2020.

11. Peter Earle, The Making of the English Middle Class: Business, Society and Family Life in London 1660-1730, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989, pp 86, 94, 95, 101. Available on line at http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft8489p27k/, accessed 17 March 2020.

12. Ibid, 102.

13. Ibid, 94.

14. Ancestry.com, “London, England, Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, 1538-1812 for William Estall,” [database on-line], Islington, St James, Clerkenwell, 1711-1726, image 5 of 193, accessed 21 Feb 2020.

15. Ancestry.com, “London, England, Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, 1538-1812 for Ann Extell,” [database on-line], City of London, All Hallows London Wall , 1675-1729, image 202 of 218, accessed 21 Feb 2020.

16. National Center for Biotechnology Information, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, “British maternal mortality in the 19th and early 20th centuries,” November 2006, 99(11): 559–563. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1633559/.

17. Ancestry.com, “London, England, Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, 1538-1812 for Leah Hott,” [database on-line], Tower Hamlets, St Mary, Whitechapel, 1711-1733, image 184 of 202, accessed 2 Dec 2018.

18. Peter Earle, The Making of the English Middle Class, 90.

19. The Worshipful Company of Cutlers, “History.”

This additional glimpse into our family’s past adds so much insight into what life portended for the Estalls. The smells, the dark, crowded streets and homes, and the early adult responsibilities for teens that had to make their own way in the world are visceral here. Early death and disease were realities of life in a way we can hardly imagine. Thank you for the hard work putting this part of our history together.