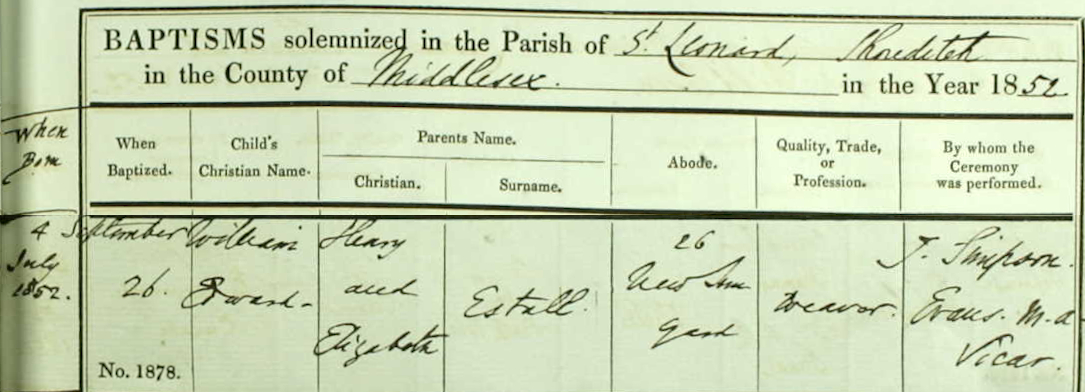

Our great-grandfather, William Edward Estall, was born in London’s Shoreditch parish in 1852, the eleventh of Henry and Elizabeth’s twelve children.

We know William was poor, based on his living in the impoverished East End. But how poor was he? Was he among the completely downtrodden of the area or was he simply among the common working poor?

We can answer these questions and better define his poverty by looking at some contemporary sources.

Background

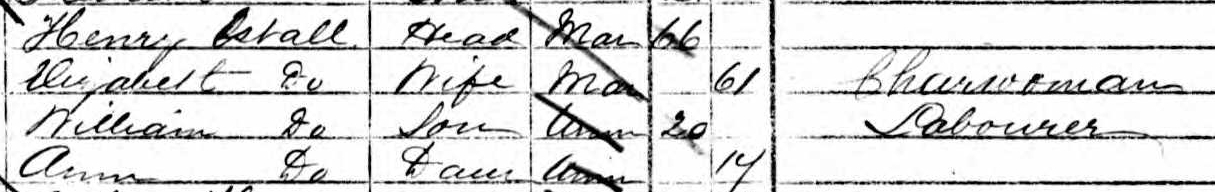

William’s father was a silk weaver, a respectable if not particularly remunerative trade. Many working class boys learned their trades from their fathers. Unfortunately William lost his dad at age 13, but even if William had been fortunate enough to learn from his father, it was a trade in severe decline due to industrialization and the lifting of protective silk tariffs, leaving its practitioners and their neighborhoods in poverty. William and his brothers — left without relevant job skills — became general laborers.

In 1871, when William was eighteen, the census recorded him as a labourer, son of a charwoman.

He tried to improve his career prospects by joining the British Army when he was 22 years old. The plan didn’t work as he’d hoped. He was discharged after four years of a twelve year enlistment due to chronic health issues including colic, contusion, fevers, boot ulcer, epilepsy, inflammation of fluids, and palpitation.

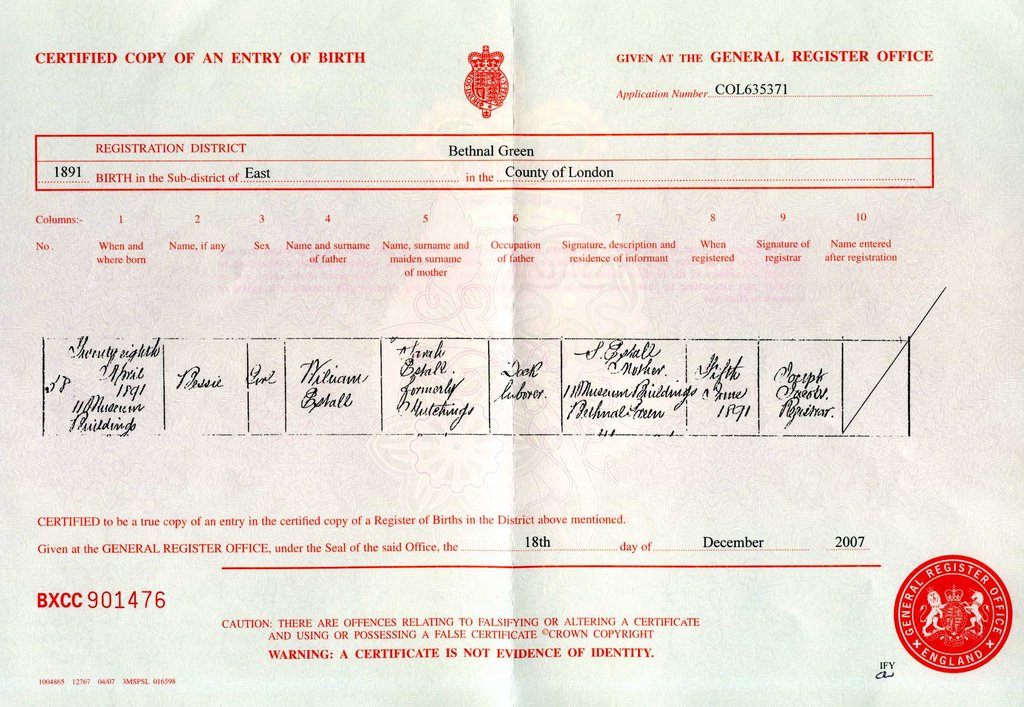

With no apprenticeship, no military prospect, and no education, William again turned to manual labor, working at various times as a builder’s, water-side, dock, ground, and general labourer. These occupations were recorded in census, military, marriage, and his children’s birth records.

His residences around Bethnal Green were similarly recorded, both before he entered the Army and after he reappeared in the parish in 1890 at age 37. [After the Army he lived for the better part of a decade in Lower Sydenham working as a labourer and raising a family with a common-law wife.]

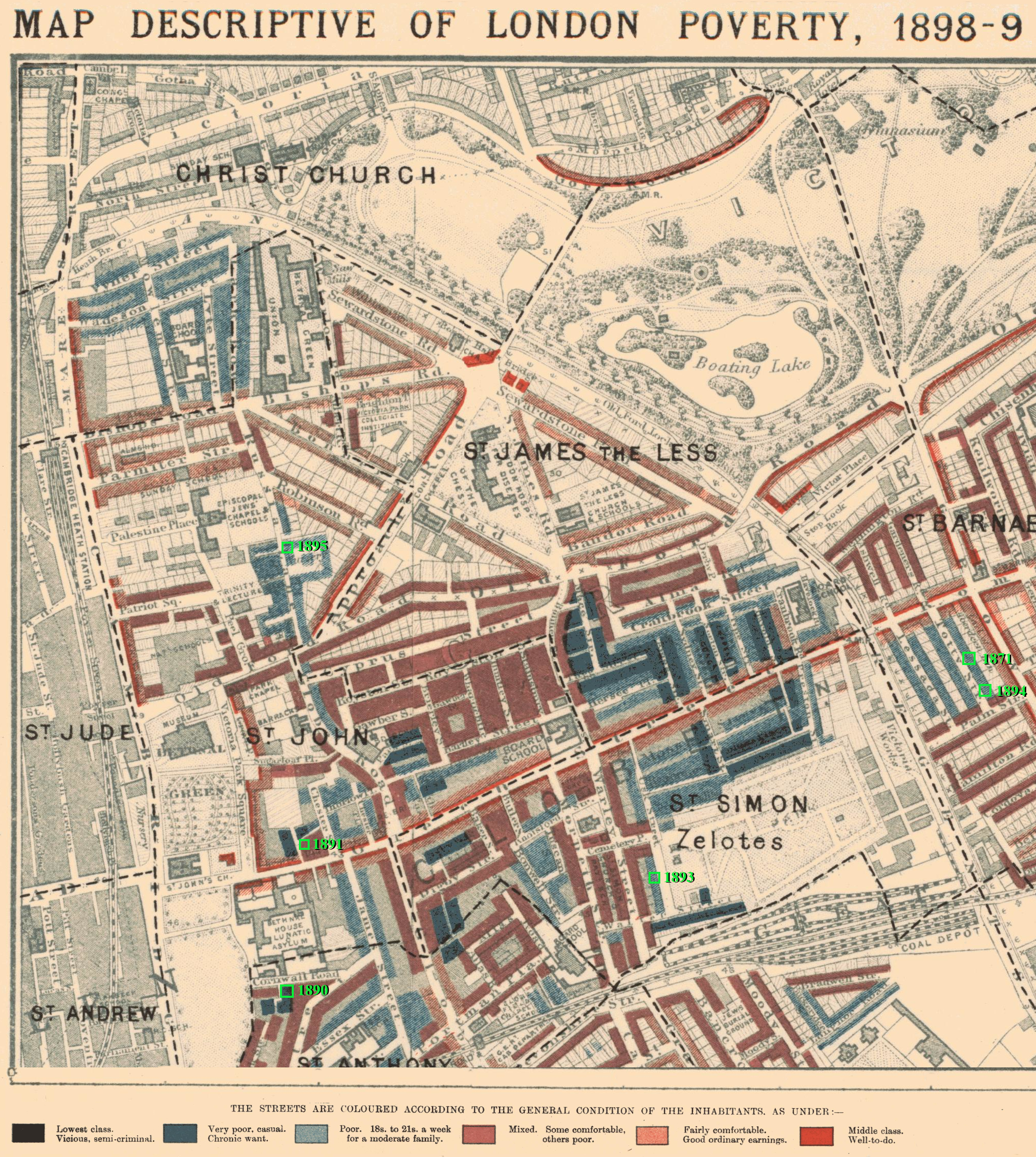

With that background, we turn to Charles Booth’s London Poverty Maps of 1898-99, specifically to the map of the Bethnal Green area, to see the conditions of the streets upon which William lived.

Poverty defined by his residences

Charles Booth and his staff walked the streets of London’s working classes between 1886 and 1903 in the company of police officers knowledgeable of their patches, making detailed observations on what they saw and heard. The notes they made were the basis of maps in which streets were color coded for the incomes and social classes of their inhabitants.

Plotting William’s residences, we see that the streets he lived on were mostly color coded light blue. Light blue indicated the street was “Poor. 18s. to 21s. a week for a moderate family.” Based on this, it appears William’s weekly wages fell in that range: between 18 and 21 shillings a week.

Poverty defined by his employment

Further clarifying his income is his history as a labourer. In the late Victorian era general laborers made only about 60% of what an artisan or a skilled laborer such as a bricklayer, carpenter, or mason earned,1 meaning William was on a lower rung of the working class.

At the time of our grandmother’s birth in 1891 he worked as a dock laborer which paid around 6 pence an hour.2 There were 12 pence in a shilling so he made half a shilling per hour. Doing the math of an 18-21 shilling weekly income (from Booth’s map) means he likely worked between 36 and 42 hours a week, considerably below the working class average of between 55 and 66 hours a week (five 10-12 hour workdays plus a half day Saturday).

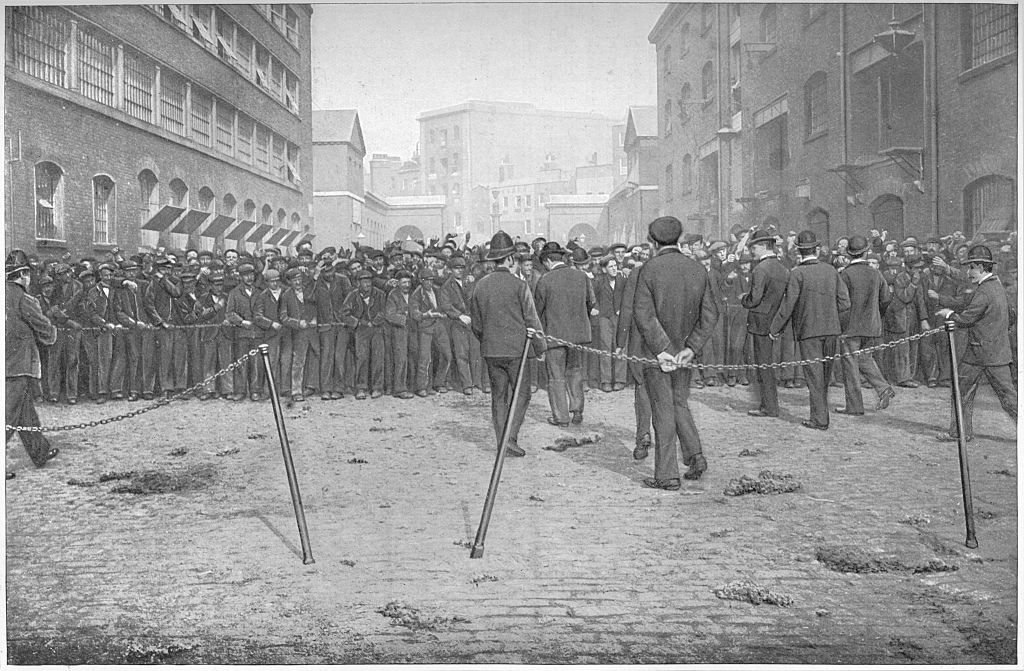

His abbreviated work schedule wouldn’t have been of his own choice. As an unskilled manual laborer he was at the mercy of seasonal and economic fluctuations — if ships weren’t available to load or unload cargo, for example, he was out of work. Furthermore, there were more laborers looking for jobs than there was work available. As reported in an 1897 newspaper, “At taking on time [time for engaging men for jobs] at certain wharves, where the foreman would come and stand at the iron gates of the wharf entrance, there would usually be a crowd of from two hundred to three hundred men. Probably seventy or eighty would be required. … The scrambles were frightful.”3

Nor would William have been favored for steady, full time dock work . . . that would have been reserved for the very fittest. William, being both older (in his late thirties and early forties) and seemingly constitutionally unhealthy, would have fallen into the category of “casual” labor, engaged for a few hours for a particular job.

“This casual labour system became so general that only a small section of port workers had anything like regular employment and the rest had to take their chance of getting a few days or a few hours work as circumstances might call for….” — from “The position of dockers and sailors in 1897″ 5

William, then, was working both for lower wages and for fewer, unpredictable hours than typical working class men. And given that he had several children and a wife to support he may have been on the high side of Booth’s definition of a moderately sized family and the low side of the income spectrum for the light-blue coded streets of his neighborhood.

Poverty defined by his cost of living

According to “Life on a Guinea a Week”6, the average cost of living for a single male clerk in London in 1888 was about 31 shillings a week, which included costs for rent, food, drink, clothes, candles, soap, and miscellany. William’s estimated income of 18-21 shillings would cover only a little over half of that.

Charles Booth described this level of ‘standard’ poverty (18-21 shillings a week) as “means [which] may be sufficient, but are barely sufficient for decent independent life.” He suggested this income level for a moderate-sized family might keep them going, but they were highly vulnerable to illness, accidents, family size increasing and loss of work or hours.7

Given that William was prone to illness, was rapidly growing his family, and worked at unsteady jobs, speculation on my part is that William’s income may have been supplemented by his wife in order to shelter, feed, and clothe the burgeoning family. Sarah was a seamstress before she married William and may well have continued to do some piece work from their flat to keep the family afloat.

William would have been paid with bronze and silver coins, and if he was lucky, they would have jingled in his pocket on the two-mile walk home from the docks.

A couple of pence would buy a pint of beer (I’m pretty sure William and Sarah, like most of their neighbors, were imbibers), and 3-6 shillings would pay for weekly rent in working class housing. Food, including bread, vegetables and fruit, flour and sugar, cost about 14 shillings a week for an average clerk, so Sarah had to squeeze the most out of every coin spent at the vendors’ barrows on nearby Green Street. Their clothing was probably mended if not made at home, further stretching their budget.

Though the money was meager, they apparently made do, as there were no records of workhouse visits or outdoor relief (payments to poor people without the requirement to enter a workhouse) while they were married. Perhaps telling, though, is that William was employed for a considerable stretch by the area council, which may indicate he received some informal relief in the form of pay for ground or general labor.

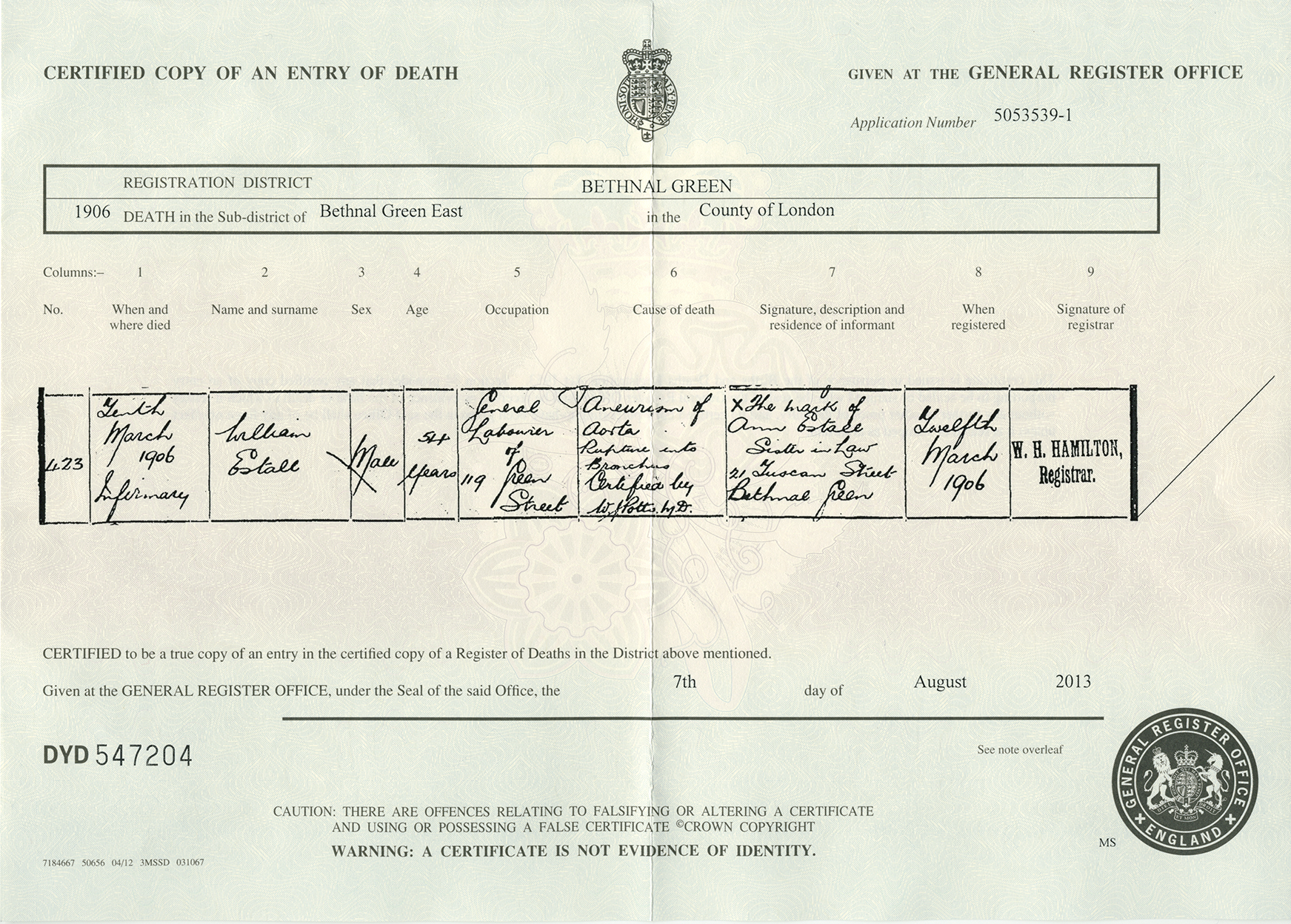

William’s economic vulnerability caught up with him in 1900 when he lost his wife to disease. After her passing he spent over a year in the workhouse hospital for bronchitis. When he got out he dropped his children off with his former common-law wife in Lower Sydenham, undoubtedly in hopes that she would care for them while he returned to Bethnal Green looking for work. The only records we have of him thereafter were three workhouse visits for more hospitalizations and finally his death at age 53 in 1906.

Taking the measure of William Estall

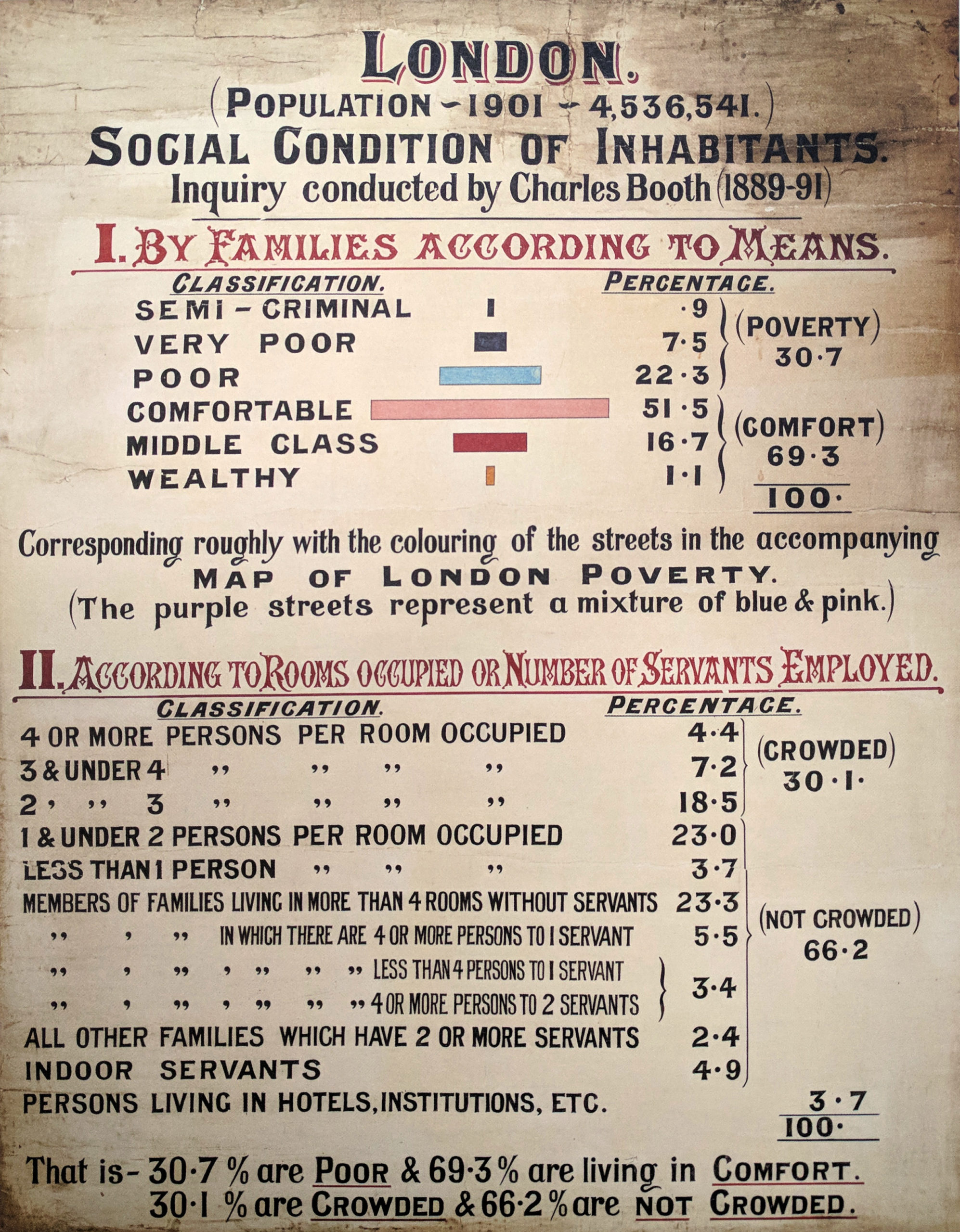

By Charles Booth’s calculations, 31% of people in London in 1901 were living in poverty and 30% were living in crowded conditions. Considering the streets William lived on (coded light blue) and the size of his family (a wife and up to seven children at home), he fell within the 22.5% of Londoners who were ‘standard’ poor and within the 4.4% of Londoners who were crowded into rooms holding 4 or more people. By that measure, William was poor — but not among the 8% in the very poor or semi-criminal classes. Nor, of course, was he among the 52% who were comfortable or the 18% in the middle or wealthy classes.

Despite the meagerness of what was in his wallet, William kept a roof over his family’s head and food on the table, no small achievement.

In sum, William wouldn’t be the subject of an abysmal Jack London story or a broken down character in a Charles Dickens novel. He was just a working family man who doggedly made ends meet on low wages and inconsistent hours. Charles Booth concluded that the greatest cause of poverty — accounting for 63% of its occurrence8 — was low pay and irregular earnings. William Estall could have served as the poster boy. Yet he wasn’t alone. He was one of many who survived, maybe just barely, on something under a pound (£) a week on the light blue shaded streets of London’s East End.

End Notes:

1. Arthur Bowley, Wages in the United Kingdom in the Nineteenth Century, (1900: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England), p. 70.

See also The Victorian Web, “Wages and Cost of Living in the Victorian Era,” http://www.victorianweb.org/economics/wages2.html

2. Clarion Newspaper Company, “The position of dockers and sailors in 1897 and the International Federation of Ship, Dock and River Workers.”

3. Ibid.

4. George R. Sims, editor, Living London, Vol. 1, (1901: Cassell and Company, Limited, London, Paris, New York & Melbourne), p 171.

5. “The position of dockers and sailors”.

6. The Victorian Web, “The Cost of Living in 1888,” from an article entitled “Life on a Guinea a Week” in The Nineteenth Century, Vol. 23 (1888), p 464.

7. Mary S. Morgan, London School of Economics, Charles Booth’s London Poverty Maps, (2019: Thames & Hudson Limited, London, England), p 30.

8. Ibid, p 41. Reproduced from a table from Charles Booth’s Life and Labour of the People in London, Poverty series, Vol. 1 (1902-03), p 147. The other causes of poverty were small profits (5%), drink (7%), drunken or thriftless wife (6%), illness or infirmity (5%), large family (9%), and illness or large family combined with irregular work (5%).

What a difficult life, but as Bill says “at least he made do. “ The health issue is the biggest factor, and being the eleventh of twelve children and a father who died early in William’s life, boded a hard scrabble for him.