Before we congratulate ourselves at having an ancestor who sailed to America on the Mayflower, let’s take a look at Edward Doty’s life in the New World. It may not prove quite as heroic as we’d hope.

It started out well. Eddie was among the first explorers sent out from the ship to find a place to build their colony. A Journal of the Pilgrims at Plymouth relates that, “Wednesday, the 6th of December, it was resolved our discoverers should set forth … So ten of our men were appointed who were of themselves willing to undertake it, to wit, Captain Standish, Master Carver, William Bradford, Edward Winslow, John Tilley, Edward Tilley, John Howland, and three of London, [i.e., Strangers:] Richard Warren, Stephen Hopkins, and Edward Dotte.”[1]

The First Encounter

The exploratory party sailed along the shore in the mid-December cold, where the water froze on their clothes making “them many times like coats of iron.” After landing, the explorers came upon a group of native Americans who weren’t exactly a welcoming party. “Anon, all upon a sudden, we heard a great and strange cry … One of our company, being abroad, came running in and cried, “They are men! Indians! Indians!” and withal, their arrows came flying amongst us. … The cry of our enemies was dreadful … their note was after this manner, “Woach woach ha ha hach woach.” Our men were no sooner come to their arms, but the enemy was ready to assault them.“[2]

The Saints and Strangers survived the attack and went on to establish a settlement at Plymouth, but the conditions were harsh, and almost half of the Mayflower’s passengers were dead within the first few months. The remaining colonists began building houses and farming in the spring, and by autumn of 1621 they had a sufficient harvest to hold a three-day feast with ninety of their now-friendly native neighbors in attendance.

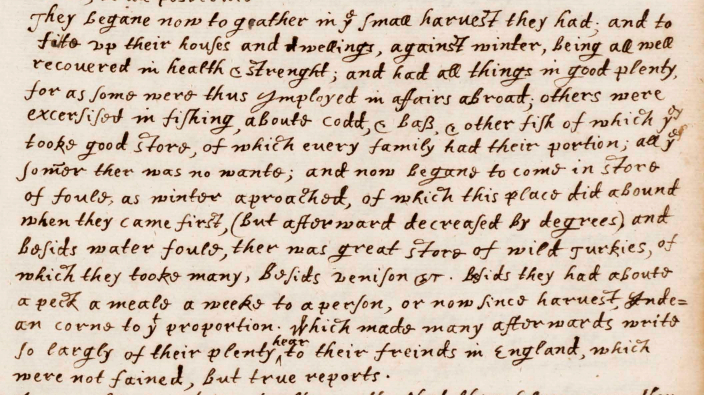

The First Thanksgiving

As related by William Bradford in his journal, “They [the colonists] began now to gather in the small harvest they had, and to fit up their houses and dwellings against winter, being all well recovered in health and strength and had all things in good plenty. For as some were thus employed in affairs abroad, others were exercised in fishing, about cod and bass and other fish, of which they took good store, of which every family had their portion. All the summer there was no want; and now began to come in store of fowl, as winter approached, of which this place did abound when they came first (but afterward decreased by degrees). And besides waterfowl there was great store of wild turkeys, of which they took many, besides venison, etc. ”

A letter sent to England described the first New England thanksgiving:

“Our harvest being gotten in … amongst other recreations, we exercised our arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and among the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five deer, which they brought to the plantation and bestowed on our governor, and upon the captain and others.”[3]

Edward Doty, of course, was among the colonists in attendance, probably in the company of his master Steven Hopkins’ family.

![]()

Perhaps less cause for celebration is Eddie’s questionable character. One Plymouth historian, Caleb Johnson, calls him a troublemaker. “He had a quick temper that often got the better of him, and he was very shrewd in his business dealing, to the point of being fraudulent in some cases.“[4] That appears to be a fairly rosy assessment.

The First Duel

His first run-in with the law came in June of 1621, with “the first duel fought in New England, upon a challenge of single combat with sword and dagger between Edward Doty and Edward Leister, servants to Mr. Hopkins; both being wounded, the one in the hand, the other in the thigh, they are adjusted by the whole company to have their head and feet tied together, and so to lie for twenty-four hours, without meat or drink, which is begun to be inflicted, but within an hour, because of their great pains, at their own and their master’s humble request, upon promise of better carriage, they are released by the governor.“[5]

When Plymouth began keeping court records in 1632 we see Eddie made no less than 23 appearances over the next twenty years for welshing on debts, slander, non-payment to his servant, fighting, fraudulent and deceitful deals, assault, trespass, and theft.

Yet Caleb Johnson says that “despite his regular appearance in Plymouth court … he carried on a regular life in Plymouth; he was a freeman with a vote at the town meetings, he paid his taxes, and he accepted the outcome of all court cases and paid all his debts. And all the while, he was raising a sizeable family. The court periodically made land grants to him, just as it did for other residents, and he participated in all the additional land benefits of being classified a ‘first comer’.”[6]

Doty, therefore, was a complicated, and flawed, character. He stayed in Plymouth until his death, contributing to and yet disturbing the common good. From our distant vantage point he probably makes a better ancestor than he made a neighbor to his contemporaries.

In the following and final post, we’ll look at Edward Doty’s family life and his death in his mid-50s.

Footnote(s)

[1]. Henry Martyn Dexter, ed, Mount’s Relation, or Journal of the Plantation at Plymouth (Boston: John Kimball Wiggin, 1865), pp 43-45.

[2]. Ibid, pp 52-53.

[3]. Ibid, p 133.

[4]. Caleb H. Johnson, The Mayflower and Her Passengers (Xlibris Corporation, 2005), p 132.

[5]. Thomas Prince, A Chronological History of New-England (Boston: Cummings, Hilliard, and Company, 1826, a new edition of the original published in Boston by Kneeland & Green in 1736), pp 190-191. (https://archive.org/details/achronologicalh00halegoog)

[6]. Johnson, The Mayflower and Her Passengers, p 135-136.