NOTE: Click on underlined links to open images of referenced documents.

Bessie Estall, our grandmother, was the daughter of a newly-married London dock worker and a seamstress. Her mother had previously given birth to three children by unnamed men; her father previously sired two children by another woman. Bessie, therefore, had five half-siblings.

This is the story of the half-brother Bessie never met, and possibly never knew about. Like many of the Estall family children, it’s a story of abandonment and evolving name identity.

Our grandmother’s half-brother, William ‘French’ Estall, was born in London in 1882. He had what appeared to be a short life, disappearing when his paper trail ended in England in 1911. His death was confirmed when his wife remarried in 1917, classifying herself a “widow” on her marriage registration. I spent a number of fruitless years looking for his death certificate and finally gave up, concluding his paperwork was lost forever.

Forever, that is, until I recently discovered he reappeared in North America. Hence, I began to think of him as the “Resurrection Man.”

Beginnings

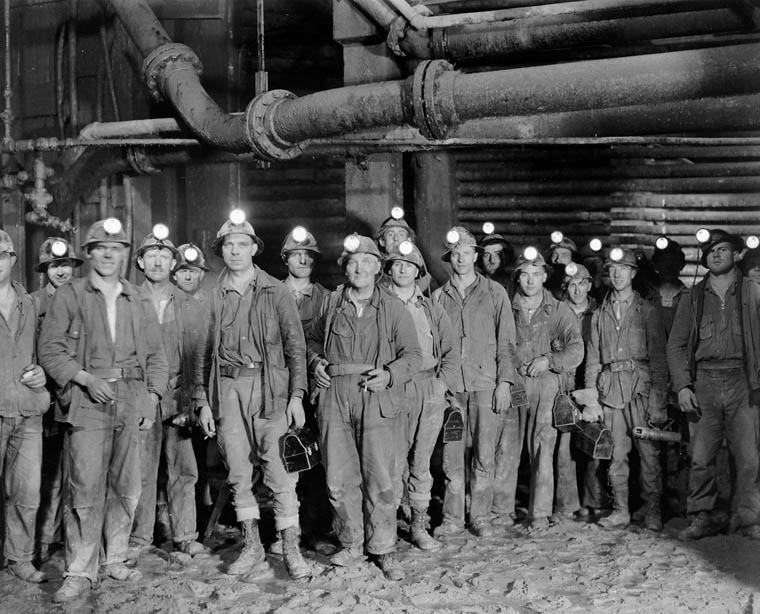

William Estall was born on 18 February 1882 in a working class neighborhood of Lower Sydenham, in the Lewisham district of London. His mother, Sarah (nee Whitmarsh) French was married . . . just not to the infant’s father.

Sarah previously had two children by her husband William French when her marriage went on hiatus and she began living with William Estall, a general labourer.

Sarah then had two children by William Estall out of wedlock: William in 1882 and Ann[1] in 1885. William’s birth registration names his mother as “Sarah Estall formerly Whitmarsh.”

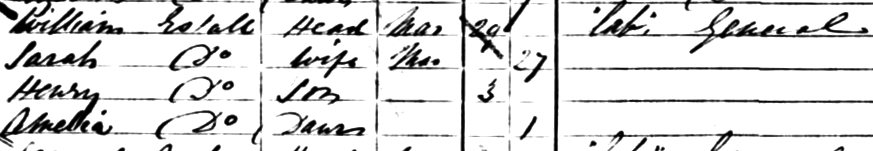

On William’s sister Ann’s birth registration, excerpted below, their mother identified herself as “Sarah Estall late French formerly Whitmarsh” which is not only a mouthful, but reflects the convoluted state of Sarah Whitmarsh’s marital condition.

Unfortunately for the children, the marriage wheel didn’t stop turning there. Their mother returned to her husband William French by the time of the 1891 census, where it shows the reunited couple raising William French’s children as well as William Estall’s son William.

Family Tensions

Tensions can arise in blended families, and apparently did so in the French household. The 1891 census shows that Ann Estall, William’s sister, was living with her grandparents rather than with her mother. Meanwhile, nine-year-old William was living with his mother and her formerly estranged husband and was now going by the surname “French,” undoubtedly a concession to the cuckolded step-father in whose house he was living.

But not living there for long.

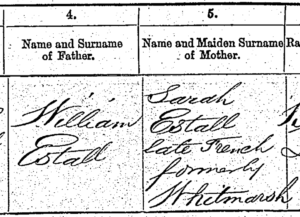

By the next year, at age 10, William was pulled out of his neighborhood school and was attending Laxon Street School, six miles from home, making it unlikely he was still living in the household. A year later, at age 11, he was enrolled on the Exmouth Training Ship docked downriver on the Thames. In effect, William ‘French’ Estall was institutionalized — read abandoned — from the age of ten, as would be our grandmother. Being a child of William Estall, Sr., didn’t provide a propitious start in life.

The young William ‘French’ Estall was assigned classes in music on the Exmouth, learning to play the bugle and clarinet. At age 13 and standing 4’4″, he was handed off to the Royal Navy in Portsmouth where he was assigned to the boys’ training ship HMS Boscawen as a “band boy.”

Ba(n)d Boy

At age 17 he was enlisted to the Royal Navy as a bandsman, playing clarinet, and upon turning 18 was embarked on a series of British battleships and cruisers stationed in the Pacific, Atlantic, and Home Fleet.

William was decades ahead of his time, the equivalent of a modern-day globe-trotting “bad boy” rock musician. His service record shows his musical ability to be ‘very good’ but he spent a great deal of time in ‘Cells’ (solitary confinement) and reduced to ‘2nd Class for Conduct’ (losing privileges and reduction of pay) for multiple instances of misconduct[2] on most of the ships to which assigned.

In 1907 at age 25 while stationed with the Home Fleet docked at Chatham, in southeast England, William took leave to return to his old neighborhood in London and marry Eliza Alice Abel. Their marriage, despite his deployments, yielded a daughter, Nellie Elizabeth French.

On his last deployment, in 1910-11 aboard the HMS Cornwall in the North America Station, he received his only “very good” character rating. He may have found this corner of the world sparked his imagination, and this may have inspired his plans for the future.

William completed his enlistment and left the service on August 9th, 1911, at the age of 29, returning to Lower Sydenham, London. That’s where his English paper trail ended. As mentioned, his wife remarried in 1917 as a widow and his daughter Nellie remains untraceable.

The First Resurrection

This was not the end of his story, though. Three months after his service discharge William — without wife or daughter though identifying himself as married — boarded a passenger ship to North America. The ship’s manifest shows he arrived in Canada in November of 1911, with the intended destination of Quebec, as a musician “going to enlist [in the] Royal Canadian Artillery.” If he went to Canada to continue a military career while maintaining a family in London, he struck out on both counts.

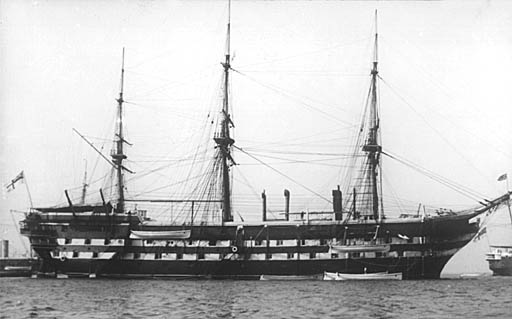

Perhaps lured by the “Porcupine Gold Rush” when gold was discovered in the area of Timmins, Ontario in 1909, William settled in Porcupine, Ontario, undoubtedly working the mines. The town, with a population of under a thousand, consisted of hastily erected wooden buildings to service the mines and miners. William stayed there a little over a year, perhaps concluding that working underground just wasn’t panning out for him.

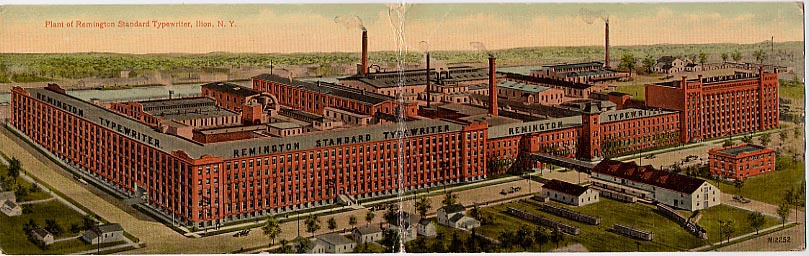

What apparently was in his sights, however, was a new life in America, a return to his birth surname, and a job with the Remington company. In the spring of 1913 William left Canada to join his friend Frederick Lloyd in Ilion, New York.

(https://herkimer.nygenweb.net/ilion/sweeney2.html)

Frederick Lloyd, five years William’s junior, grew up in the same London neighborhood as William and also ended up with the Royal Marines Band. He, too, was a clarinet player, and served on some of the same ships and attended some of the same music classes as William. Lloyd left the Marines in 1909, and emigrated to the United States in 1912. He was living in Ilion, New York, in March of 1913 when William Estall decided to join him there. Given that Remington (of firearms and typewriters fame) was the major employer in the town, and that Lloyd went on to become a machinist — a trade one would learn in a factory — it’s likely Lloyd worked for Remington and that William took a job with the company as well. William, however, didn’t pursue a trade like his buddy did. Lloyd went off to Canada to serve with their Armed Forces during World War I and later ended up in Royal Oak, Michigan, working at a Ford Motor plant. William apparently remained in America but dropped off the paper grid for the better part of two decades.

Ironically, if William had followed Lloyd’s lead and headed to the Detroit, Michigan, area, he would have lived in the same city as his half-sister Bessie, though they may not have been aware of the other.

The Second Resurrection

William reappears in the 1930 census in Manitee, Florida, working as a farm laborer at at truck farm. It may have been William’s nature to tweak the nose of authority, either in jest or defiance; his history of detentions with the Royal Marines demonstrated that. The trait continued, as evidenced by his answers to the censuses of both 1930 and 1940, in which William identified himself as being a native of India, with an Irish mother and a French father.[3] Those bizarre assertions made him difficult to track in the censuses, but the 1940 census, which places this man of so-called Indian descent with his wife Lois in Destin, Florida, confirms it was him.

In 1933, at age 51, William married a 23-year-old southerner, Lois Margret Huff, in her home town of Rockmart, Georgia. By 1940 Lois was living with William in Destin on the coastal Florida panhandle. The census paints a portrait of William trying to make a living as a music teacher — his Royal Marine records show he was both a clarinet and violin player — but apparently struggling at it. He had been out of work for most of the previous year, earning a paltry $90 when the mean annual income of the time was $956.[4]

Even more distressing was his divorce two years later from Lois, which she filed because of his “habitually intemperance [read drunkenness] and cruelty.” Their marriage lasted nine years and didn’t result in any children. Whether William was cruel or a drunkard is debatable, though, given that Lois immediately remarried and then divorced her second husband four years afterwards citing the same causes. (This in the days before no-fault divorce.)

His occupation of last resort turned out to be a fisherman, as he reported in his application for U.S. naturalization in 1951.

Destin, on the Gulf of Mexico coast, is still known for its fishing. I bought a cap there in 2009, long before I knew this was William’s last home.

The naturalization application also reveals the evolution of William’s name and identity. William was born an Estall, became a French from at least the ages of nine through 29, entered America as an Eastle, was occasionally an Estelle (like my grandmother), and died an Estall. His forenames were equally fluid: he came to Canada with a self-assigned middle name of Ed, assumed the first name of “Jack” at times in Florida, and died with Jack as a middle name.

William Jack Estall died on July 17, 1954, at age 74 in Destin, Florida of pneumonia and arteriosclerotic heart disease, with senility and anemia thrown in for good measure. Interestingly, the informant was his ex-wife Lois Margaret Cook — she having remarried (twice) and divorced — indicating there may have been a reconciliation of sorts between them. She reported his usual occupation as musician, his birthplace as Bombay, India, and she missed his birth date by two years, which mistake was perpetuated on his grave stone.

William had tried his hand as a military musician, miner, factory worker, farm laborer, music teacher, and fisherman. He may have had a drinking problem, he didn’t much respect authority, and he seems to have been a trouble maker. He failed at two marriages and abandoned his only daughter. A case could be made he was his father’s son but I won’t be the one to make it. He was, after all, my grandmother’s half-brother and my grand uncle.

His body was buried at the Marler Memorial Cemetery in Destin, Florida, and if I pass that way again I’ll visit his grave site, give my regards from his half-sister, and share a sip of ‘Jack’ with him for old time’s sake.

That is, of course, unless he’s had a third, miraculous, resurrection.

(https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/15542148/william-j-estall)

Footnotes

[1] Ann Estall, our grandmother’s half-sister, lived to the age of 86, residing in Lewisham, London, her entire life. Growing up she lived with her mother’s parents Henry and Sarah Whitmarsh. (Our grandmother Bessie Estall may have met Ann when their father dropped his children off on Henry Whitmarsh’s doorstep in 1901 before Bessie was turned over to the workhouse.)

Ann married Hugh Duffy, a labourer, in 1905 at age 20 while working as a laundress, and had seven children, all sons, between 1905 and 1921. She worked domestic duties after her husband died in 1938. Ann passed away in the spring of 1971.

[2] “2nd Class for Conduct” was awarded in cases of gross insubordination, dishonesty, or gross misconduct, and also to men for whose continual slackness or misconduct the repeated award of minor punishment proved ineffective. “Cell” is solitary confinement in a cell, with forfeiture of wages, reduced diet, no bedding, limited exercise, and assignment of two pounds of oakum picking daily. (The King’s Regulations and Admiralty Instructions for the Government of His Majesty’s Naval Service, 1913, pp 254, 256.)

[3] Bessie Estall also thought she was of French lineage as evidenced by her entry document to the United States in 1911. The idea, though mistaken, may have been verbalized by their father.

[4] National Public Radio, “The 1940 Census: 72-Year-Old Secrets Revealed,” https://www.npr.org/2012/04/02/149575704/the-1940-census-72-year-old-secrets-revealed, accessed 15 Dec 2020.

What a wonderfully written article! I have been researching this same William French Estall, as he seemed, based on DNA evidence, the most likely of the French family to be my great-grandfather who we knew as William Given. It was discovering the US Naturalization document that made it obvious that I had been wrong.

I still don’t know the birth name of my great-grandfather, or how he came to be in Canada. Was he a British Home Child perhaps? We may never know.

Do you have any photos of William French Estall? I would be interested in comparing them to those I have of my great-grandfather.

By the way, the mention of French heritage may not be incorrect. I know from tracing the trees of our DNA matches that we have strong French Huguenot roots in both Spitalfields, London, England and Quebec, Canada.

Unfortunately, I don’t have any photographs of William French Estall. Would have been nice if I had and you could have compared them to your great-grandfather. Good luck in finding him. If I can help, let me know.