James Matthew McCrie went down with the RMS Titanic on 15 April 1912. Why he was on the ill-fated ship has been the subject of conjecture.

Beginnings

James (Jim) was born on July 4th, 1879, the son of Matthew and Roxanna (Harrington) McCrie. His father was the last of William and Margaret (Miller) McCrie’s nine children born in Ayrshire, Scotland, shortly before the family emigrated to Canada in 1852. His mother was born in Scarborough Township east of Toronto, Canada, in 1849.

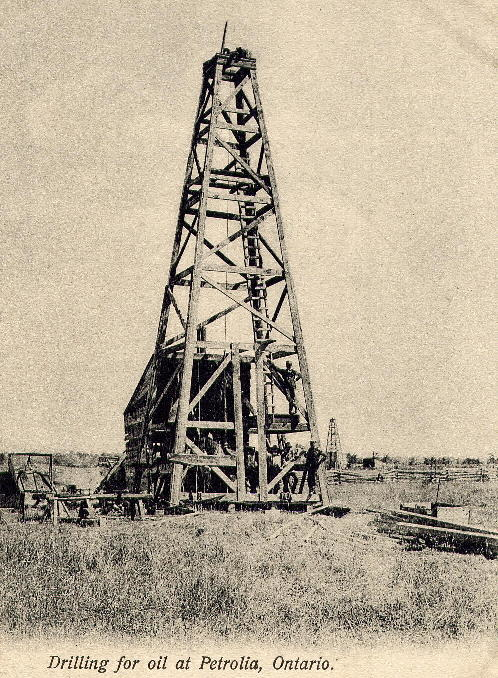

Jim’s father Matthew McCrie was a farmer and oil producer, living two lots east of his own father’s farm on Churchill Line road, southeast of Sarnia, Ontario, and northwest of the small town of Petrolia in Enniskillen Township. In addition to farming and oil production, Matthew McCrie, the father, performed public service as a town assessor, a township auditor, and a school board member, a natural interest given that Matthew’s own father (Jim’s grandfather) was a teacher.[1]

James was born on the family farm, the third of eight children. He helped his dad through his teen years but when he turned twenty he headed north to Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, to be with his pregnant 17-year-old girlfriend, Maud Brown, whose family had relocated there from Enniskillen.[2]

Family Life

He took a job as a laborer in the Canadian “Soo,” and in June 1900 he and Maud crossed onto the American side to get married by a justice of the peace before Maud delivered their first daughter, Margaret Irene, back on the Canadian side a couple of weeks following. A year later the 1901 Canadian census reported him working as a blacksmith in Sault Ste. Marie.

Shortly thereafter, however, James—with his new wife and daughter in tow—returned to his father’s farm, where he resumed farming and working the oil fields.[3]

James and Maud had their second daughter, Francis May, in April 1902. He then moved his growing family three lots west and settled next to his grandfather’s farm where they had their third daughter, Eveline Pearl in June of 1904.

Their fourth and last child, Elsie Maud, was born in December 1906. On the birth register James was reported as a “driller.” That occupation is confirmed in a 1906 biographical history of the county which reported that “James, born in 1879, married Maud Brown, of Lambton County, and lives in Sarnia township, where he is engaged in drilling for oil.”

Sadly, the blessing of four daughters was tempered by the loss of their third one, Eveline Pearl, at the age of 11 months in May of 1905. The register lists her cause of death as “scalded” and length of illness as 31 hours. Those would have been unimaginably painful hours for the young parents as well as the infant.

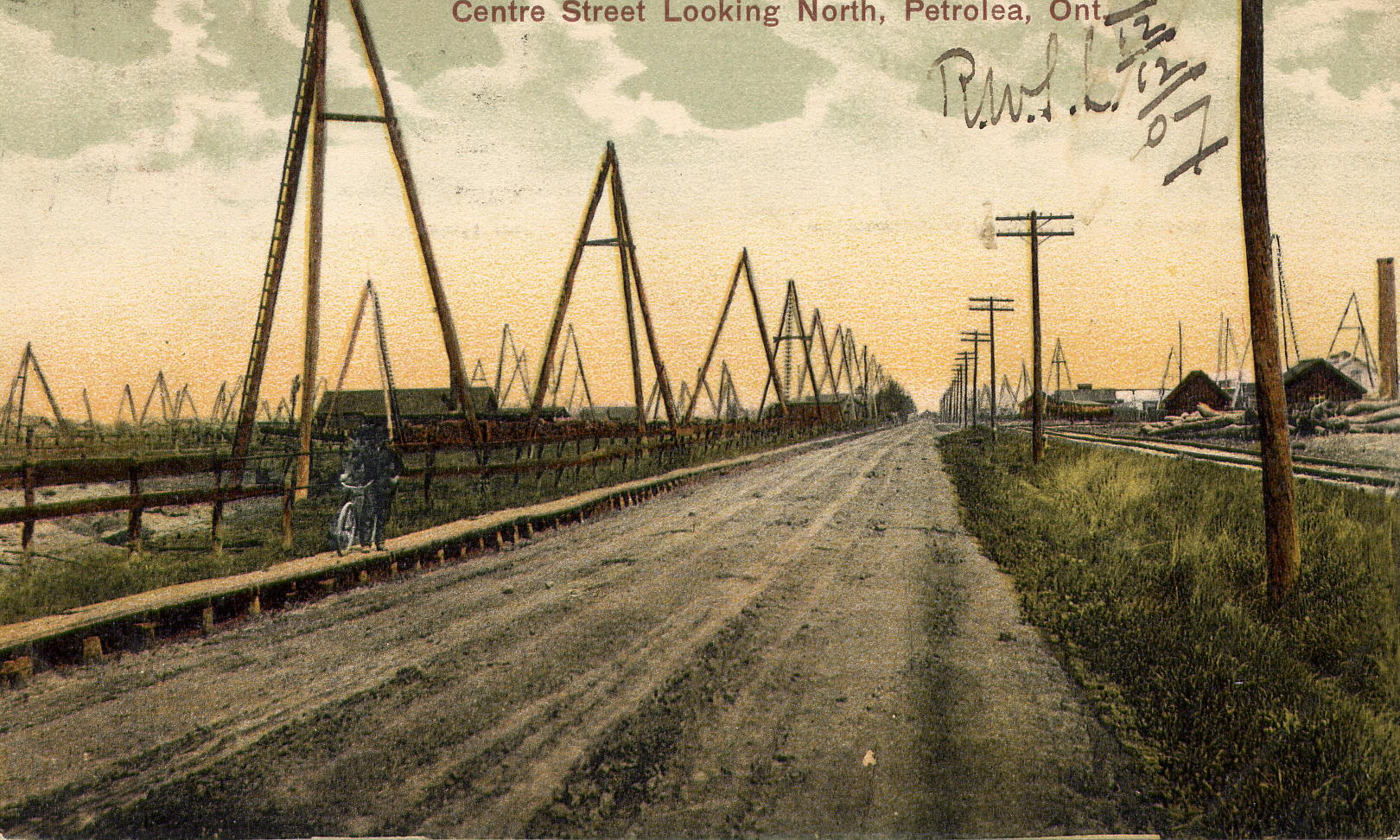

The Oil Capital of the World

Oil drilling in all of North America began in Enniskillen Township in 1858 when James Miller Williams successfully extracted barrels of oil from an area of sticky crude “gum beds” caused by underground oil seepage. (You will be forgiven if the theme music from the old television show Beverly Hillbillies begins playing in your head.) In the early 1860s the area was the “Oil Capital of the World,” with wells extracting crude oil, which was then transported to newly built refineries in Sarnia, and shipped as far away as England. Derricks sprang up in the town of Oil Springs, and as those wells played out, production moved north to Petrolia, which became a boom town.[4] It was natural that Matthew McCrie and his son James became oil men, supplementing their farm income with the fruits of black gold extraction.

Over the next few decades as the wells dried up, many Petrolia area men who worked them took their expertise and tools to other promising locations around the world. A 1913 article in the Detroit Free Press, titled “When Oil Gushed at Petrolia,” concluded with:

“Many drillers still live in Petrolia, but most of the heads of families are scattered over the face of the globe, where they go on punching holes in the ground and sending their wages back to the loved ones in the oil town.”

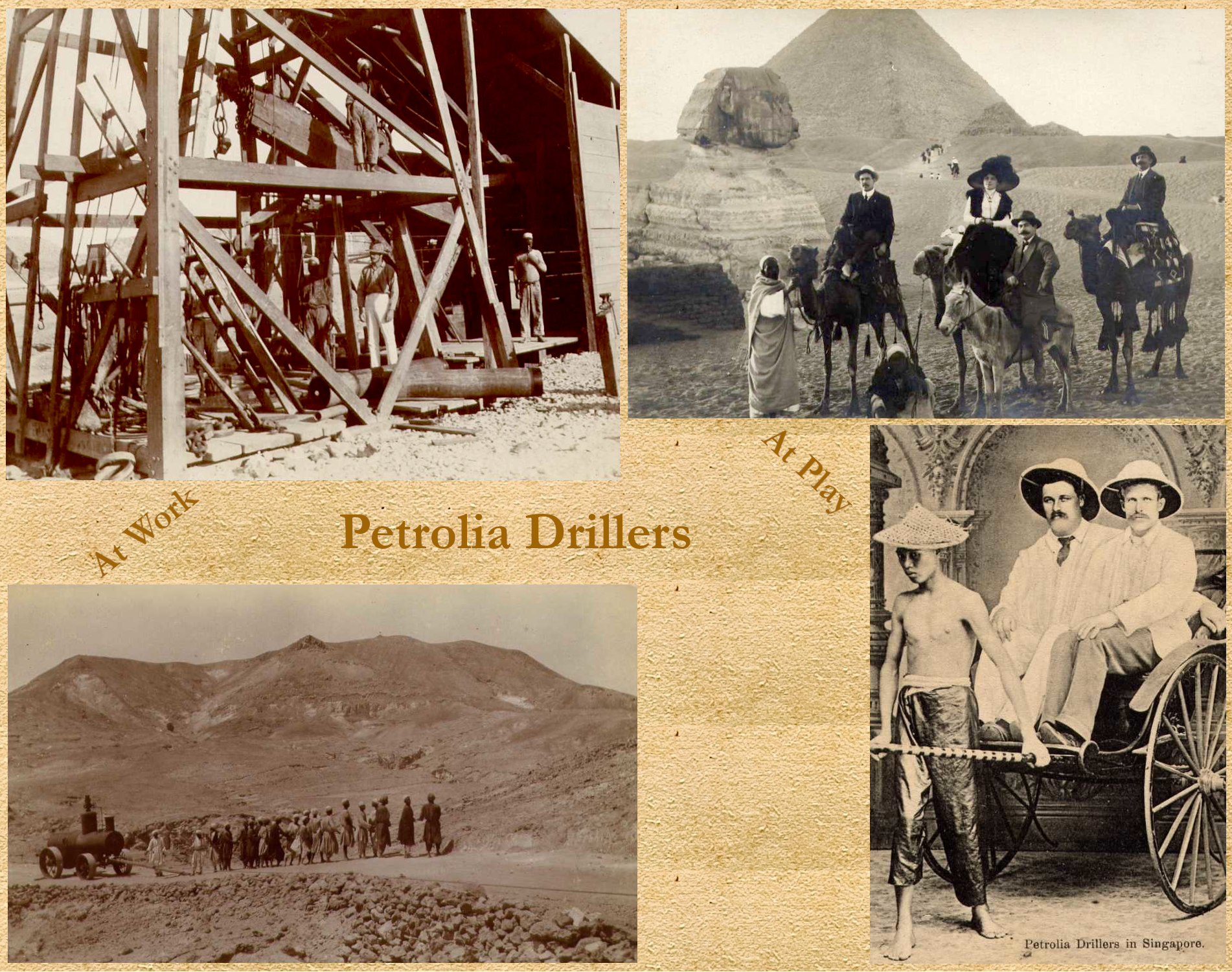

Foreign Driller

Such was the case with James Matthew McCrie who went overseas to ply his expertise in oil drilling in order to support his family. Ship passenger records show he sailed from New York to Singapore in February 1907 with five other Enniskillen men listed as “boremasters.” They returned in April of 1908 from Yokohama, Japan.[5]

In May of 1911 he sailed from New York to London on his way to Egypt.[6] A picture of him and fellow Enniskillen drillers in Egypt, below, shows he was tall and strongly built. Although the caption says it was taken around 1900, it dates to 1911 or 1912.

A niece of his related, “My dad said Jim was so interesting, that he would come back home from those trips and tell so many good stories.”[7] Home by then was a house in the town of Sarnia, Ontario, where he sent his earnings while the family awaited his visits between overseas jobs.

If Jim suffered separation loneliness, the home front had issues of its own. According to a Red Cross record,[8] his daughters had physical ailments that must have challenged his wife Maud:

“The eldest is a cripple from hip disease. The second is in frail health, threatened with throat tuberculosis. … [and] after her father’s departure for England, the youngest daughter suffered an attack of infantile paralysis, which has left one ankle useless for life.”

It may have been these conditions which prompted James to return home when he did. One account says, “He rushed back home, 503 North 16th Street, Sarnia, Ontario, Canada, because one of his three children was dying from tuberculosis and he wanted to comfort his distraught wife.”[9]

Another account said he “learned his wife Maude (nee Brown) in Sarnia was sick and was coming back home on the Titanic.”[10]

Yet another account says he and his buddy Gus Slack were on furlough and Gus offered him his own ticket for the Titanic because Jim’s wife was ill. According to that account, “At that time, all the tickets were sold out but Gus decided to go visit a friend somewhere in England and give up his ticket.”[11]

Jim’s niece and nephew recall hearing that the company he worked for gave him a ticket on the Titanic as a bonus, or that Jim demanded a Titanic ticket as “one of the perks of the job.”[12]

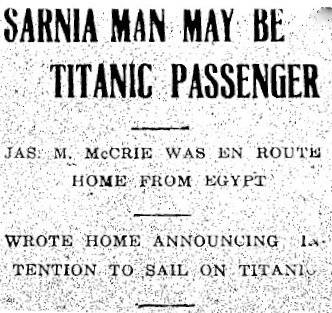

Of all the accounts, the one with the most credence probably comes from a contemporary article in The Sarnia Daily Observer of April 16, 1912, which read:

“Mr. McCrie, who is a driller by occupation, has been engaged in that pursuit for the past eighteen months or so in Egypt. A short time ago his contract expired and he was on his way home to Sarnia. A letter recently received from him by Mrs. McCrie announced his arrival in England and also conveyed the information that he intended to remain over in England a week in order to make the passage across the ocean on the new steamer Titanic.”

“Mr. McCrie, who is a driller by occupation, has been engaged in that pursuit for the past eighteen months or so in Egypt. A short time ago his contract expired and he was on his way home to Sarnia. A letter recently received from him by Mrs. McCrie announced his arrival in England and also conveyed the information that he intended to remain over in England a week in order to make the passage across the ocean on the new steamer Titanic.”

Regardless of how he obtained the ship ticket, it seems clear he was looking forward to the trip on the world’s largest — and luxurious — liner, and he arranged his return accordingly.

The aforementioned Red Cross record also mentioned that “he had written to them [his family] that he would remain at home, permanently.” Had he made it, home life would have been far different than before, with the daughters, ranging in age from six to twelve, having their father around to help raise them.

The Ill-Fated Voyage

While in London waiting for his sailing date, James stayed at the new Strand Palace Hotel in the center of the city near the River Thames. On the 10th of April he walked across the Waterloo Bridge to the Waterloo Station to catch the Boat Train to Southampton,[13] the port city on the southern cost of England, and boarded the Titantic for her maiden voyage. He held a second class ticket, enjoying the comfort of the ship, though not the opulent amenities reserved for its first class passengers.[14]

The ship launched around noon on the 10th, made stops at Cherbourg, France, and Queenstown, Ireland, and set sail the afternoon of April 11th, 1912, for New York with 1,137 passengers and 885 crew aboard.

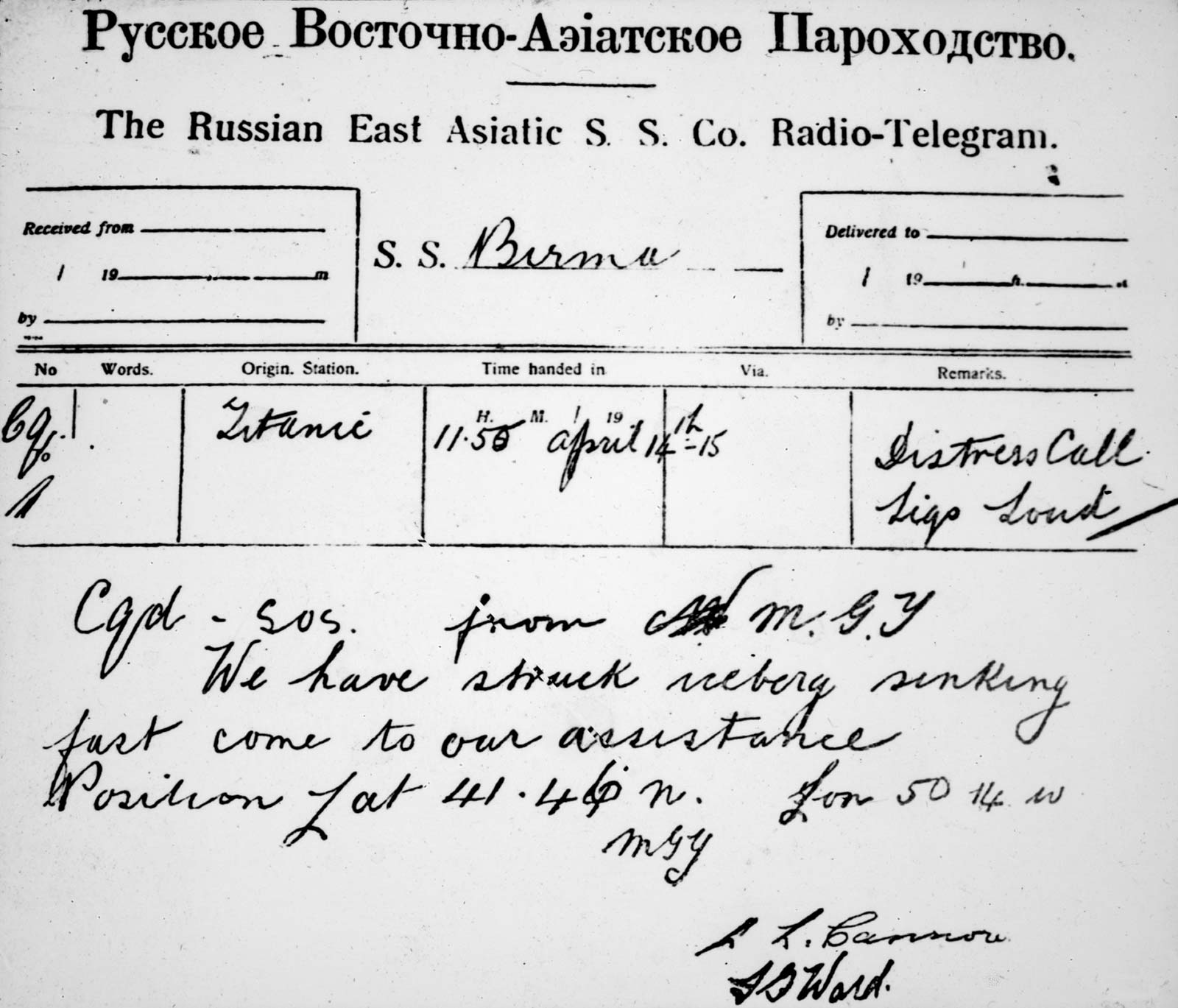

On the night of the 14th the Titanic entered a patch of sea known to have icebergs, but maintained its speed of 22 knots, despite receiving warnings from two other ships in the area: the Mesaba warned the Titanic’s radio operator of an ice field at 9:40 p.m. and the Californian sent word at 10:55 p.m. that it had stopped after becoming surrounded by ice. The Titanic’s radio operator, who was busy handling routine passenger messages, scolded the Californian for interrupting him and didn’t pass the messages to the bridge.

It was the lookouts in the crow’s nest who spotted an iceberg at 11:40 p.m. but it was too late to avoid a collision. The starboard side scraped along the iceberg and the ship’s hull was punctured along six of its sixteen supposedly watertight compartments.

At 12:05 a.m. the first orders to abandon ship were given and its too-few lifeboats were deployed. Distress signals (flares) were sent out by 12:15 a.m.; by 1:00 a.m. water was seen at the base of the Grand Staircase; and around 2:00 a.m. the stern’s propellers were clearly visible above the water as the bow had plunged below water. At approximately 2:18 a.m. the lights on the ship went out, it broke in two with a groan, an eerie rattle, and a roar, and at 2:20 a.m. the stern also disappeared beneath the ocean. The ship sank within three hours of hitting the iceberg. Hundreds of passengers and crew went into the icy water where they either died from drowning or exposure. More than 1,500 lives were lost.

Among them, James Matthew McCrie, age 32: son, brother, husband, father, oil driller and provider. His body was not recovered.

The aftermath

Jim’s wife Maud went to Detroit four months after the loss of her husband to work as a nurse at Bowland Sanitarium, apparently leaving her daughters with her mother and sister until she could get settled. The children were reunited with their mother by 1915.[15]

In 1916 at age 33 Maud married George Kienle, an automotive supply clerk four years her junior, in Detroit. They had no children together, and in the 1930 census she wasn’t living with George and listed herself as divorced, though in later years they were together again. She died in 1965 at age 82.

The youngest daughter, Elsie, was married and divorced three times and died childless at age 53. The eldest daughter, Margaret “Irene” married at age 36 and also had no children. The middle daughter, Frances, had two marriages and three children.

Whether any of the sisters had long-term effects from their childhood diseases is unknown, as is whether separation from their father, and temporarily from their mother, played a part in their later spousal relationships.

A 13-minute video on the history of oil and oilmen in Enniskillen Township during James McCrie and his father’s lifetimes is available from the Oil Museum of Canada on YouTube (click link to open). The video includes the photograph of Jim McCrie and his mates in Egypt shown above.

Footnotes

[1] J. H. Beers & Co., compiler, Commemorative Biographical Record of the County of Lambton, Ontario. (Toronto: The Hill Binding Co, 1906), 124-125. Available at the Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/recordlambton00beeruoft/page/124/mode/2up.

[2] The Canada census of 1891 places the Brown family in Enniskillen. In September 1898 one of Maud’s brothers, Henry, was married in Sarnia and listed Enniskillen as his residence. The 1901 census puts the Brown family in Sault Ste. Marie. It’s reasonable to assume, therefore, that Maud’s family moved to Sault Ste. Marie some time after Maud’s pregnancy began in September 1899.

[3] James McCrie is listed as a farmer living on his father’s lot at the birth of their second daughter in April 1902.

[4] Fathi Habashi, “The First Oil Well in the World,” Bulletin for the History of Chemistry, Vol 25, No. 1 (2000): 64. Avilalable online at http://acshist.scs.illinois.edu/bulletin_open_access/v25-1/v25-1%20p64-66.pdf.

[5] Ancestry.com, “UK and Ireland, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960 for J M McCrie,” Southampton, England, 1907, Feb, image 32 of 62; “UK and Ireland, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960 for J McCrie,” Southampton, 1907, February, image 41 of 124; “UK and Ireland, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960 for F McCrie,” Southampton, England, 1908, Apr, image 63 of 278.

[6] Ancestry.com, “UK and Ireland, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960 for M McCrie,” London, England, 1911, May, image 204 of 312.

[7] “The Untold Story of Sarnia’s Role in a Night to Remember,” The Sarnia Observer, July 19, 1997, B7. (Transcript available at https://www.ancestry.com/mediaui-viewer/collection/1030/tree/8102249/person/24449722694/media/5c731c85-788e-4d17-8aee-258702b23257?_phsrc=vEA126&usePUBJs=true, accessed 4 Feb 2021.) The original resource is listed in the Lambton County Museums Catalogue, as Accession Number NEWS0000000000053352, though no digital image is available.

[8] Encyclopedia Titanica, “Mr. James Matthew McCrie,” https://www.encyclopedia-titanica.org/titanic-victim/james-matthew-mccrie.html.

[9] Ibid.

[10] “The Untold Story of Sarnia’s Role in a Night to Remember.”

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Titanic-Titanic.com, “Southampton and Titanic,” http://www.titanic-titanic.com/southampton-and-titanic/.

[14] Ancestry.com, “UK, RMS Titanic, Crew Records, 1912 for James M McCrie,” Passengers Surviving or Missing, Image 16 of 33.

[15] Ancestry.com, “U.S., Border Crossings from Canada to U.S., 1895-1960 for Minnie Maud McCrie” shows she arrived unaccompanied at Port Huron on 14 August 1912; “U.S., Border Crossings from Canada to U.S., 1895-1960 for Frances McCrie” shows Frances arrived unaccompanied on 3 March 1914; and the 1930 U.S. census shows the youngest daughter, Elsie, came to America in 1915.

Such a sad story. When we saw the exhibit at the Henry Ford Museum, they had James, whom they called Matthew, traveling in steerage, where most were unable to get to lifeboats, thus perishing.

You are the more dependable resource. It does show that there are some gaps in what transpired long ago.

Maud and her girls suffered so much. The illnesses and “scaulding” make one shudder. Modern knowledge and medicine is under- appreciated.

I wonder if those McCries attended the annual McCrie picnic in Sarnia”s Canatera Park? Perhaps we have met Maud and the girls.

Thank you, Jamie, for such an interesting presentation of our distant cousin and family.

I don’t know if they attended the McCrie reunions, but their names and addresses were in the McCrie Family Book that was apparently passed to the next year’s picnic organizer every year. In 1960, Maud and two of her daughters were on the contact list:

• Maude Kenley (the mother) in Algonac

• Mr. & Mrs. Ed Gagne in Alpena (the eldest daughter Margaret Irene)

• Mrs. E. M. Viger – deceased, of Algonac (the youngest daughter Elsie, who died in August of that year)

Given that Maud and Elsie lived in Algonac it seems quite possible they attended the reunions.