Yes, I’m a relic. But that’s not what I’m writing about. (We may get around to that later, time permitting of course.)

Relics serve the useful purpose of reminding us of people, places, or times past.

The year 2019 was memorable, worthy of a relic. My sister and I explored our family history in London, walking the streets and visiting the sites where our ancestors lived going back to our great-g-g-g-g-g-grandparents. And that’s just on our father’s side; on our mother’s side we visited family neighborhoods inhabited by our great-g-g-g-g-g-g-g-g-g-g-grandparents.

The year was also memorable for seeing the publication of my book Footprints, which explored the history of these English ancestors.

So I couldn’t let the year lapse without marking its significance. I wanted a “relic” that honored our visit to London, our English ancestors, and my book publication. A relic that was English, old fashioned, and had a connection to writing.

The solution: an English fountain pen. And I found one with a brand name that stretches back to the years my grandmother, who was born in London, lived there. A pen with a technology our grandmother would have used in her school which we visited. A pen I can use to make notes for my follow-on book.

The pen is an Onoto![]() , or as its engraved barrel says, “Onoto the Pen”.

, or as its engraved barrel says, “Onoto the Pen”.

Since I like to name my fountain pens after figures in my family, I’ve named mine “the Estall.” The pen will commemorate the seven generations of Estalls who inhabited London as tallow chandlers, silk weavers, dock workers, general labourers, and lastly as orphans.

Onoto pens got their start in 1905, a year before our grandmother’s emigration to Canada. The London-based company De La Rue started making fountain pens in 1881, predating her birth, and in 1905 they began making the first self-filling fountain pen guaranteed not to leak, which they dubbed the Onoto, in their factory on Bunhill Row in London, not far from where our great-grandfather was born.

My pen doesn’t go back that far, of course. It was born on 12 December 2019. And though it uses an outdated technology (really, who uses fountain pens these days?) it writes far better than modern-day biros (that’s ball-point pens to us Americans). The model I bought, the Magna Classic, is styled after an Onoto model designed in 1937. It may look dated but that’s kind of the point — it reminds me of olde London. It is, after all, going to be my “relic.”

A history of the company and its pens is available at A Brief History of Onoto Pens, the De La Rue heritage site, or the Onoto web site.

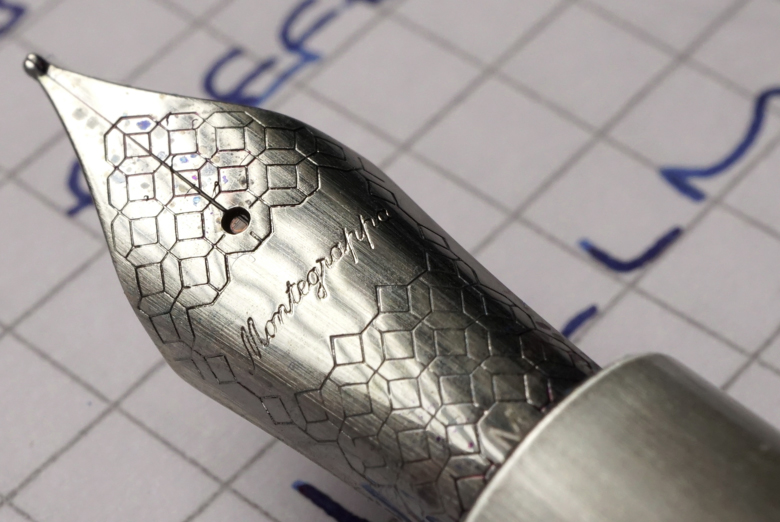

My black and silver Magna Classic has a chasing pattern engraved in its cap and body. My other black pen, a Montblanc 149, is rather plain and stodgy, whereas the chasing on the Onoto gives it some character. In place of Montblanc’s snow-capped top, the Onoto has a carved silver company logo, giving it a unique vibe, if not the prestigious brand recognition of a Montblanc. The pen has flat ends rather than than the rounded ends of the cigar shaped Montblanc, and I’m partial to the flat design which my favorite pen brand Pelikan also uses.

The Onoto and Montblanc both have 18 carat gold nibs. I like the size of the Montblanc’s nib, which is massive, but truth to tell, the writing experience with the Onoto is better. The Montblanc was a pretty terrible writer until the nib was tuned by a professional; the Onoto on the other hand wrote perfectly right out of the box, as smoothly as butter sliding over a hot English muffin. Perhaps that’s because the nib is wet and writes more like a broad than a medium.

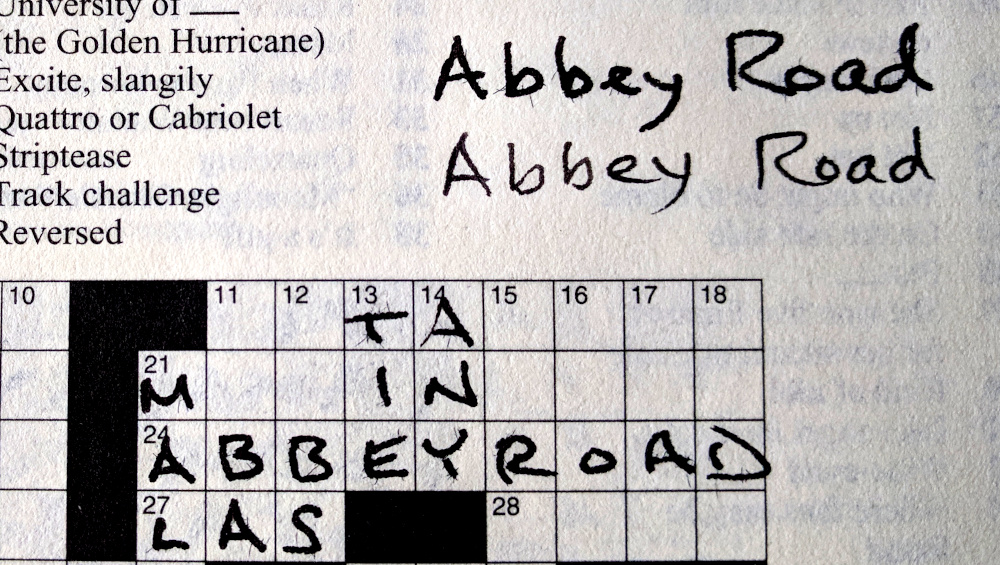

The other cool feature of the Onoto is that its nib is a “duo point,” which puts down a medium (I’d call it medium broad) size line when writing in the nib-side-up position and a fine line when the nib is turned over in the feed-side-up position. It’s like having two pens in one. I use the medium side for journaling and notes, and the fine side for entries in my small date book. Medium for daily crossword puzzles, fine for the smaller squared Sunday puzzles. You get the idea.

The Onoto Magna Classic is considered a luxury pen, similar to the Montblanc, though not quite as expensive as its German cousin. The Onoto has hallmarked sterling silver furniture — clip, rings, and buttons on the cap and barrel — as well as a gold nib. Unlike the Montblanc’s piston ink filling system, the Onoto uses a converter, which reduces its cost, though one can buy an optional plunger filler, bringing it more in line with the Montblanc price tag. I’m perfectly happy with a converter system that will prove to be easier to maintain and/or replace over the years.

The Onoto pen is a good size. It’s the same size as a Pelikan M800, which some pen connoisseurs consider the ideal size for a pen. The Onoto has the advantage of a longer grip section, keeping the threads away from fingers. The Onoto’s moderate size also makes it easier to write with than, say, the Montblanc 149 oversize pen.

Our Estall ancestors were not perfect. Nor is my Estall pen. A minor downside is the threading which attaches the cap to the barrel. Most pens are secured with one (Pelikan) or two (Montblanc) rotations of the cap. The Onoto takes four. That could be an issue for a student who is capping and uncapping her pen while taking frequent class notes. By the time the cap comes off, the history professor may be halfway into the next century. But for me who usually writes in longer sessions, cap rotations are not an issue. As a family historian I might even speculate there’s an advantage to stories written with more turns of the screw.

Another criticism I’ve read of the pen is its light weight. I didn’t think that would bother me, but based on pen reviews I ordered the optional brass weight in the pen barrel, and my Onoto’s barrel is now the same weight — 21 grams — as the Pelikan M800 barrel. Ideal size, ideal weight.

Although I don’t put much stock in packaging material, I’d be remiss not to mention the eye-catching, highly polished solid burl wood box the pen came in. It’s relic-worthy in itself and something I’m likely to keep on my desk for years to come.

I’ll always have a soft spot for the year 2019. And now I’ll always have my “Estall” pen to remind me of our trip to London, of our ancestors, and of the year that I connected with them in a very tactile way.

better homage to Bessie than a pen that when capped literally has an ace up its sleeve. Bessie would have loved the symbolism. She occasionally joked that one of us was holding one up ours when a card game was going against her. Conversely we’d tease her when she gleefully laid down a run of high-scoring aces.

better homage to Bessie than a pen that when capped literally has an ace up its sleeve. Bessie would have loved the symbolism. She occasionally joked that one of us was holding one up ours when a card game was going against her. Conversely we’d tease her when she gleefully laid down a run of high-scoring aces.

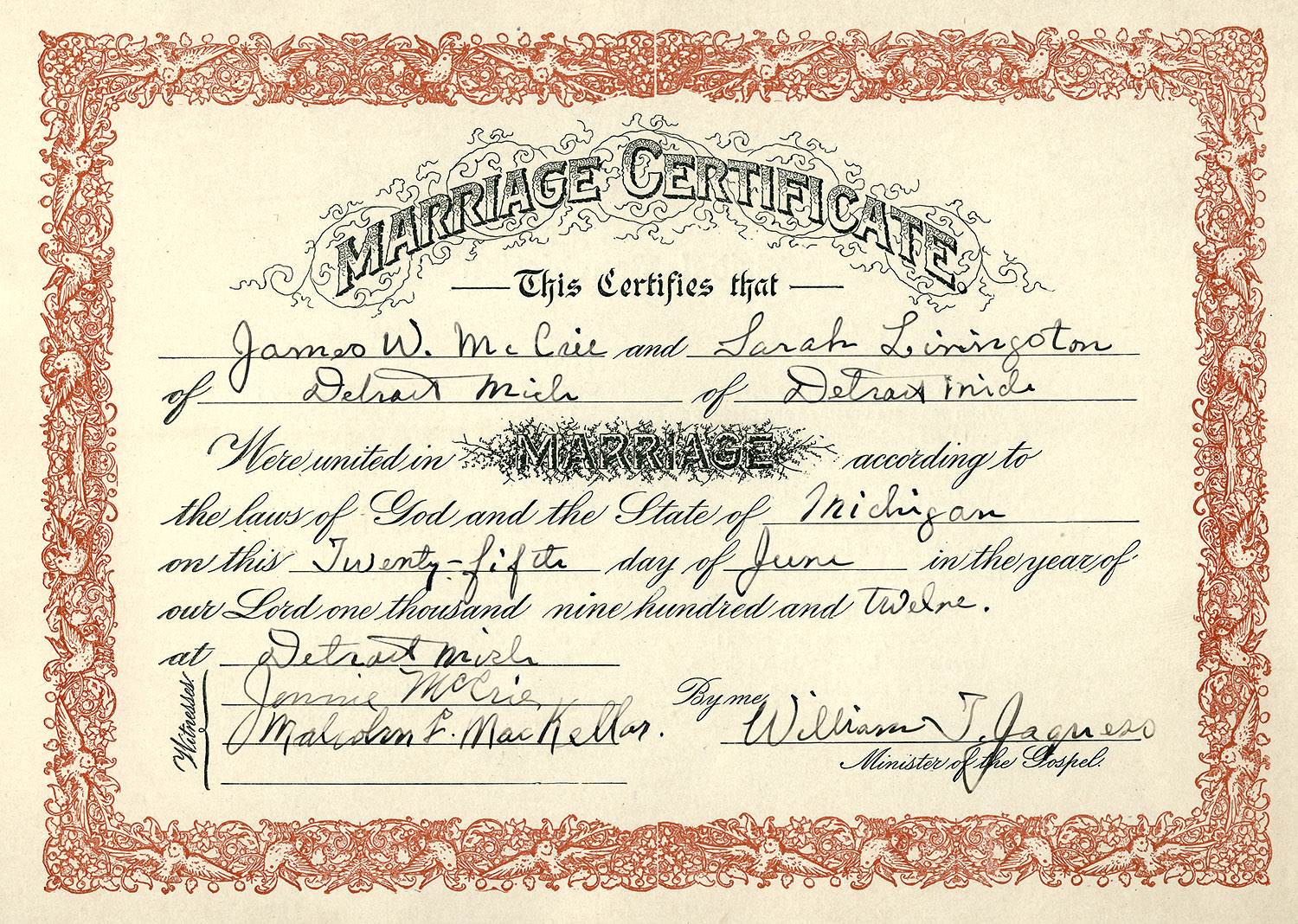

The Pelikan I’ve named in his honor is not as quiet as was James, and that’s a shame. The nib has an annoying habit of “singing” when I write in cursive. Beyond the screech, however, the pen is a joy to hold and pleasurably springy to write with, given the nib’s gold content and its massive size — the nib is the size of the last joint on my pinky finger.

The Pelikan I’ve named in his honor is not as quiet as was James, and that’s a shame. The nib has an annoying habit of “singing” when I write in cursive. Beyond the screech, however, the pen is a joy to hold and pleasurably springy to write with, given the nib’s gold content and its massive size — the nib is the size of the last joint on my pinky finger.