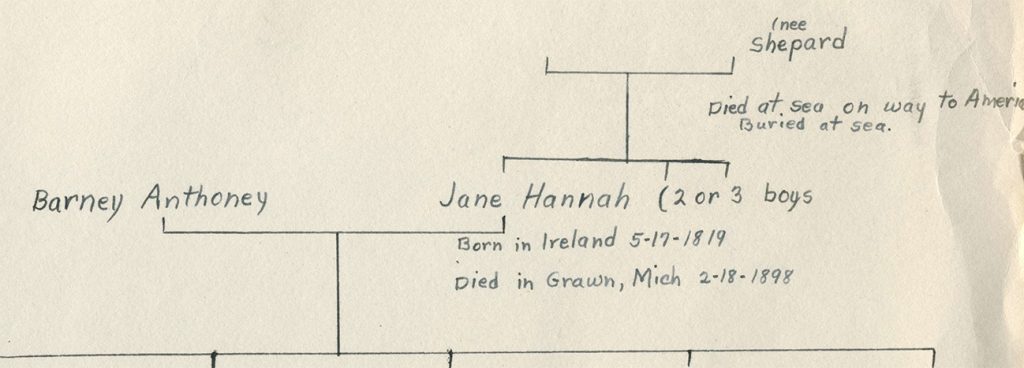

The eldest sons of four generations — from my dad to my grandchild — have Thomas as a middle name.

I suspect my grandmother Bessie (nee Estall) Schutze gave my dad his middle name in honor of her brother Thomas. Since there were no other Thomases on either side of the family, that appears to be a safe bet. Somehow the name stuck, and we continue to use it as a middle name in the family.

It seems like a good idea to know a bit about the man whose name survived despite never having had children of his own.

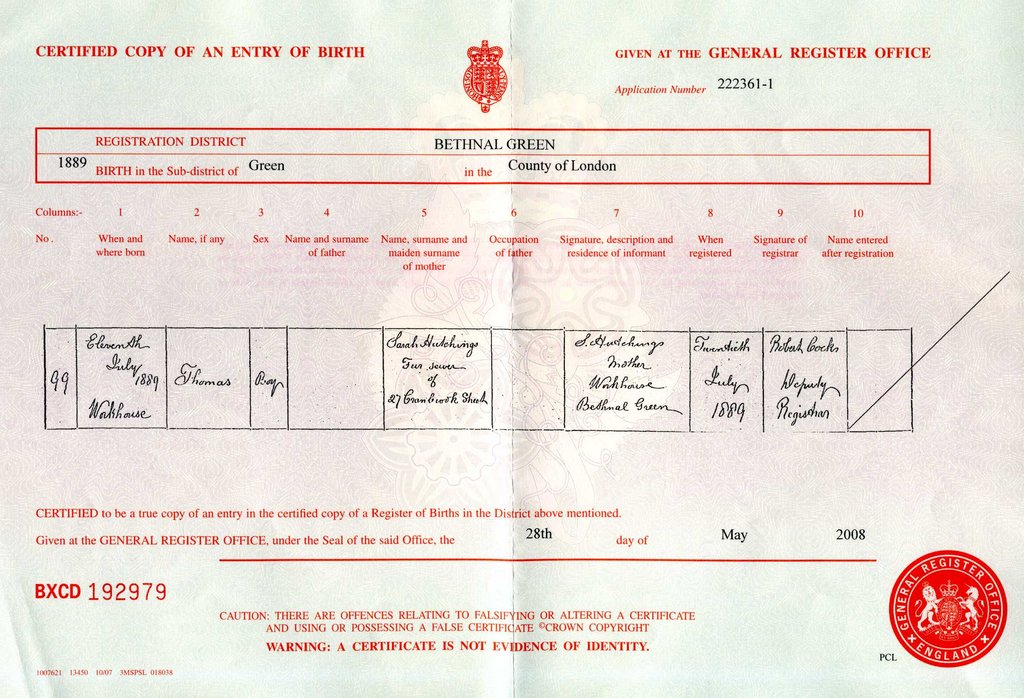

Thomas was the third illegitimate child of Sarah Hutchings, a ‘fur sewer’ living in Bethnal Green in London’s notoriously poor, overcrowded, and crime-ridden East End. An Estall family historian believes Thomas’s mother Sarah — in light of her frequent visits to the workhouse to deliver children without a father — was a prostitute. If so, she wasn’t alone: up to one in eight women of the East End turned to the trade to make a living or supplement their meager wages.

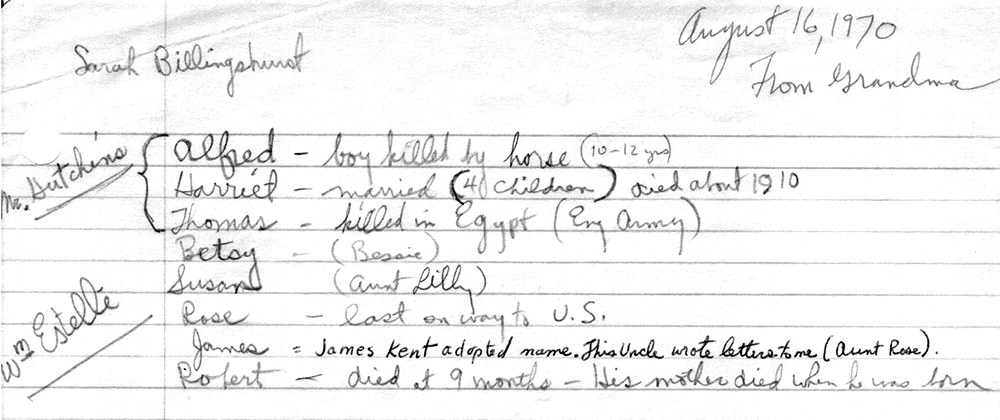

Thomas was born in the Bethnal Green Workhouse in July of 1889. He had a brother (or more likely a half-brother) Alfred, who was five years older; and a sister (or half-sister) Harriett who was three years older.

A couple of years after Thomas’s birth his mother married a laborer, William Estall, who was working the shipping docks. And a month after that his mother delivered Thomas’s half-sister Bessie, my grandmother.

[As an aside, with Sarah Hutchings’s possible occupation as a prostitute and Bessie being born only a month after Sarah’s marriage to William Estall, one may wonder whether Bessie was really his daughter. However William was living with Sarah at least ten months prior to Bessie’s birth, and Bessie needed an operation for the same condition that killed her father (an aortic aneurysm), so her claim on the Estall name appears solid.]

The Estall family lived in multi-story brick tenements around Bethnal Green. At first they lived behind a lunatic asylum on Cornwell Road. Their next home, where Bessie was born, was across the street from the other side of the asylum on Green Street. (The building, Museum House, still stands at the present-day corner of Roman Road and Burnham Street.) Within a couple of years they were living at a place on Russia Lane a police inspector described as among those where ‘there are no worse places to be found.’

Thomas lost his older brother Alfred in early 1894 to diphtheria (though Bessie, then 3 years old, thought he’d been killed on the street by a horse). Thomas, at four years of age, became the eldest son in the family. The streets were the playgrounds of the families in the East End. Thomas and his friend William Morris got lost on the streets when Thomas was just shy of five years old, and a police constable delivered the two boys to the Mile End Workhouse . The children were later returned to their parents.

Thomas and his younger sister Bessie were enrolled in the Globe Road primary school when he was six. He likely was protective of his four-year-old sister, as older siblings tend to be. Bessie would have looked to her half-brother as both a playmate and role model.

More children followed in the Estall family: Lily came after Bessie, then Rosie, then James, and Robert. Seven children and two parents would have strained the tiny living space available in tenement quarters.

Things went from bad to worse. Their mother Sarah took ill after delivering Robert, and she died of acute meningitis on Christmas Eve of 1899 at the age of 39. The family was now motherless. Thomas’s step-father William, who had a history of physical ailments, reported to the Bethnal Green Workhouse infirmary with his family, and the children — less Bessie who was also kept in the infirmary; Robert, who died in his first year; and James, who was adopted out — were sent to the Leytonstone Workhouse School a few miles away. Thomas was ten years old.

Thomas, as the oldest of the siblings at the Leytonstone School, likely would have felt responsible for watching over his sisters Lily and Rosie and keeping the family together, such as it was.

After a year and a half at the school Thomas’s step-father William was released from the workhouse infirmary and the family was reunited. With no mother to watch the children, however, William was incapable of making a living while raising the family alone.

William’s solution seems questionable. He had ten siblings, at least one of which was living in Bethnal Green. But rather than turning to them — the children’s aunts and uncles — William decided to drop off the children with a former “wife’s” family in Lewisham in southeast London.

The term ‘wife’ is used loosely. William had moved in with a married woman, Sarah French, a decade before marrying Sarah Hutchings. He had two children by her but moved on when her husband returned.

Perhaps William wanted all of his children to be together under one roof. But nobody in Lewisham was buying it, and when William abandoned them there, they were promptly dropped off at the Lewisham Workhouse.

Thomas was motherless, abandoned, and the head of the remaining Estall family. He was twelve years old.

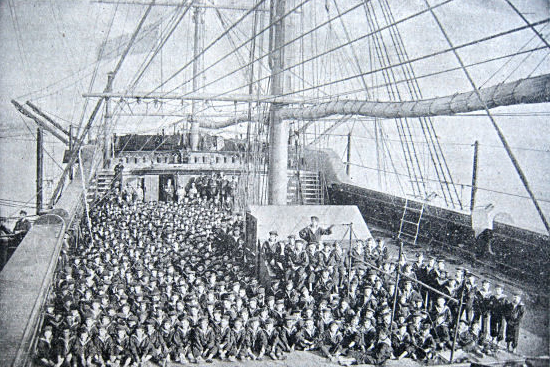

His sisters were admitted to the Workhouse school, and Thomas was sent off for boarding and instruction on the London Asylum Board’s training ship Exmouth moored in the Thames. He spent 2-1/2 years learning seaman’s duties, then was hired as a deck boy on the coal cargo ship S.S. Turkistan at age 14.

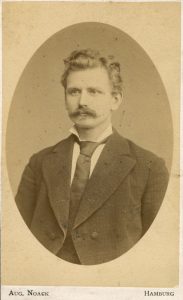

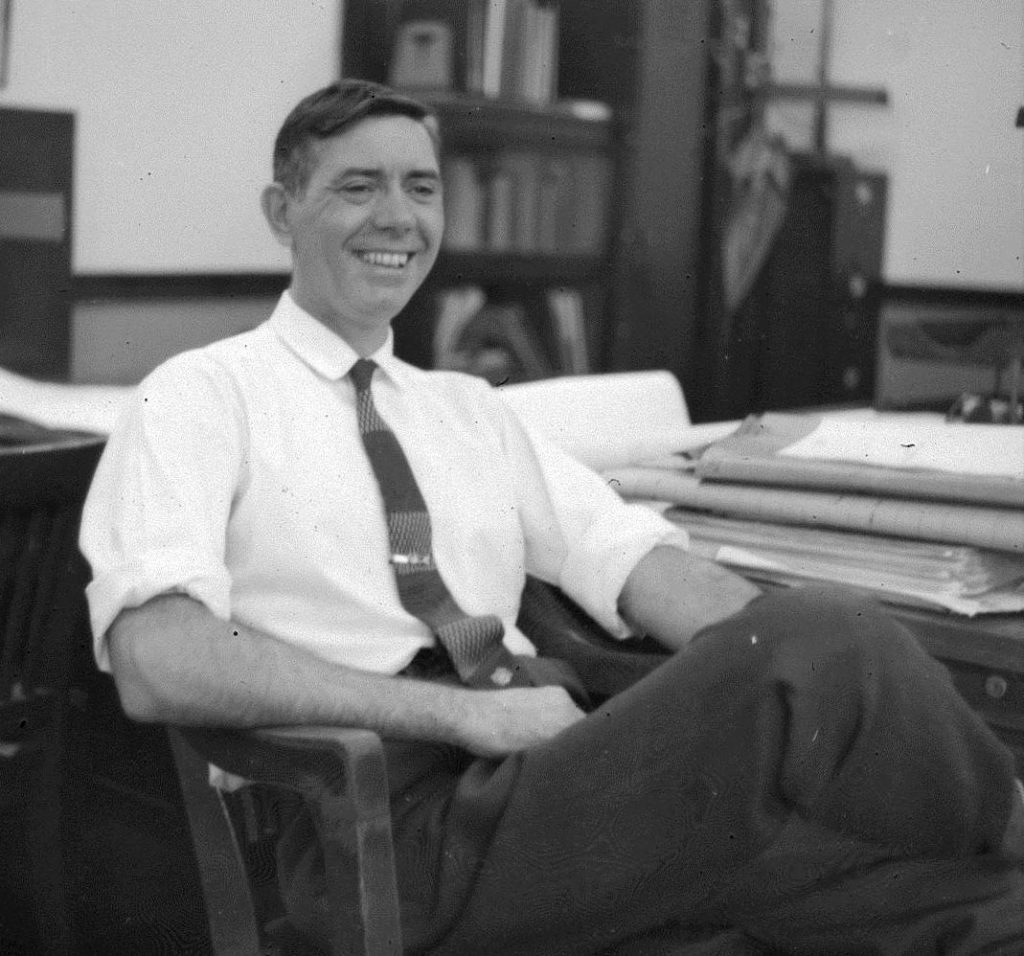

After a couple of years at sea he seems to have become a photographer for a short stint before joining the British army in southwest England in 1907 at age 18. His enlistment papers showed him to be 5’8,” 125 pounds, blue-eyed, and brown-haired.

He was assigned to a rifle company and spent his first two years training and on duty in England. In October of 1909 he was assigned to the British Egyptian Expeditionary Force in Alexandria, Egypt.

While there, he was admitted three times to the Army hospital in Cairo. An accident on duty resulted in contusion of his right foot that exacerbated an old injury and left him hospitalized for three months and caused him pain thereafter. In August of 1910 he spent two weeks in the hospital for dysphoria — a profound state of unease or dissatisfaction, which can accompany depression, anxiety, or agitation.

His physical and mental pain seem to have overwhelmed him, and in September, at age 21, while sitting on his barracks bed, he propped a rifle between his legs and committed suicide. He was buried in the English cemetery in Cairo the next day.

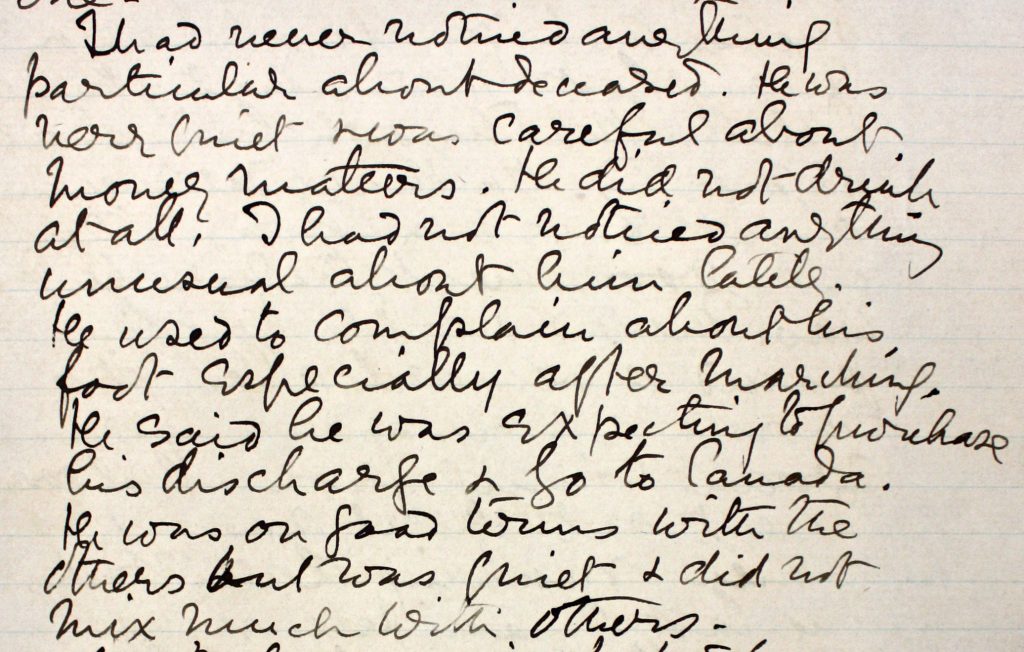

At the inquest into his death his acting corporal said “he was very quiet, very careful about money mattters. He did not drink at all. I had not noticed anything unusual about him lately. [Did his corporal not know about his recent hospitalization for dysphoria?] He used to complain about his foot especially after marching. He said he was expecting to purchase his discharge and go to Canada. He was on good terms with the others but was quiet and did not mix much with others.”

So ended the hard and short life of Thomas Hutchings. Though a Hutchings, he went by the Estall surname of his step-father. He apparently had dreams of emigrating to Canada, probably to be with his sisters Bessie and Lily who’d emigrated there in 1906 under the aegis of an orphanage.

My grandmother once mentioned to me that she had a brother who’d died while serving with the British Army and there was a great deal of pride in her voice when she said it. When she had her first son in April, 1912, she gave him the middle name of Thomas, and I’m quite sure it was to honor the recently deceased lad who had accompanied her to primary school, shared the family’s shabby lodgings, and was the closest thing she had to a father figure after her dad abandoned the family.

I consider it an honor to have his name too.

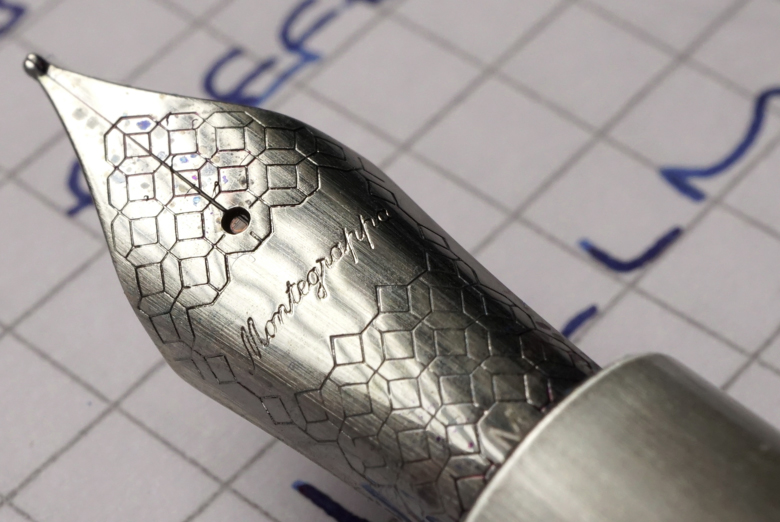

The Pelikan I’ve named in his honor is not as quiet as was James, and that’s a shame. The nib has an annoying habit of “singing” when I write in cursive. Beyond the screech, however, the pen is a joy to hold and pleasurably springy to write with, given the nib’s gold content and its massive size — the nib is the size of the last joint on my pinky finger.

The Pelikan I’ve named in his honor is not as quiet as was James, and that’s a shame. The nib has an annoying habit of “singing” when I write in cursive. Beyond the screech, however, the pen is a joy to hold and pleasurably springy to write with, given the nib’s gold content and its massive size — the nib is the size of the last joint on my pinky finger.