Jack the Ripper

The infamous Jack the Ripper was a contemporary of our great-grandmother Sarah Hutchings. Jack’s bloody rampage occurred in the autumn of 1888 in London’s East End. At the time Sarah was 28 years old, an unmarried working class mother who was also living in the East End. Research into Sarah’s life logically invites a look at the story of this famous criminal’s spree — if for no other reason than to get a glimpse into conditions in this sector of London in the late Victorian age. So it was that I picked up the critically acclaimed book about the Ripper’s victims, The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed By Jack the Ripper by Hallie Rubenhold. The book examines the lives of the five working class victims, how they grew up, how social conditions affected them and other women of their era, and how their individual circumstances brought them to the impoverished East End. Their stories provide some insights into Sarah Hutchings’ world as well. Ms. Rubenhold exposes the moral double standards applied to women vs. men, the living conditions in public housing, the difficulties of poverty, and in general the challenges of being a unprivileged woman in Victorian London. The book is a sad, but recommended, read.

Their stories provide some insights into Sarah Hutchings’ world as well. Ms. Rubenhold exposes the moral double standards applied to women vs. men, the living conditions in public housing, the difficulties of poverty, and in general the challenges of being a unprivileged woman in Victorian London. The book is a sad, but recommended, read.

The book has another, though indirect, connection to Sarah Hutchings. A leading newspaper’s interview with the book’s author was written by Sian Cain, who currently lives in the flat that Sarah Hutchings occupied in 1891. The interview is at The Guardian newspaper’s web site.

Sarah Hutchings

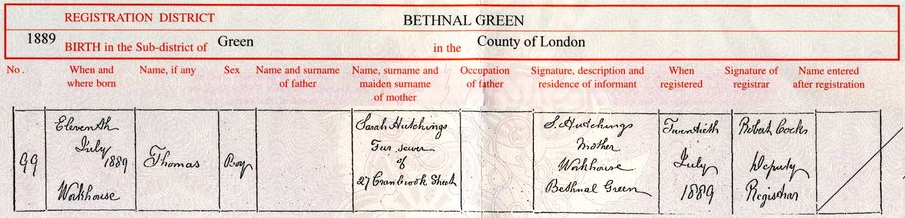

As mentioned in an earlier post, an Estall family historian believes Sarah Hutchings was a prostitute — a suspicion based on the fact that she had three children out of wedlock to unnamed fathers while frequently changing residences in London’s impoverished East End. After reading The Five, I came to realize that Sarah was indeed a prostitute, or at least considered one by many people of her era. Here’s a passage from The Five: “From the introduction of the Contagious Diseases Acts in the 1860s through the period of the Whitechapel murders, very few authorities, including the Metropolitan Police, could agree as to what exactly constituted a ‘prostitute’ and how she might be identified. Was a prostitute simply a woman like Mary Jane Kelly who earned her income solely through the sex trade and who self-identified as part of this profession, or could the term prostitute be more broadly defined? Was a prostitute a woman who accepted a drink from a man who then accompanied her to a lodging house, paid for a bed, had sex with her, and stayed the night? … A woman who had sex for money twice over the course of a week, before finding work in a laundry and meeting a man whom she decided to live with out of wedlock? … A young factory worker who had sex with the boys who courted her and bought her gifts? … A woman with three children by three different fathers who lived with a man simply because he kept a roof over their heads? “Some of these women might be classed as professional or “common prostitutes,’ while others might be called “casual prostitutes’ or just women who, in accordance with the social norms of their community, had sex outside of wedlock. But as the Metropolitan Police came to recognize, the lines separating these groups were often so blurred that it was impossible to distinguish between them.”1 Another author, Judith Flanders (The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens’ London), clarifies that “the word ‘prostitute’ was not used entirely the way we would use it today, i.e. to refer only to women who sold their bodies for sex. In the 19th century, many people used it more widely, to refer to women who were living with men outside marriage, or women who had had illegitimate children, or women who perhaps had relations with men, but for pleasure rather than money.”2 Under Victorian mores and definitions, then, it would seem that Sarah Hutchings was a prostitute, though there is no evidence (for example, a criminal record) clarifying whether a professional or moral one.A Difficult Life

Sarah worked at various times as a barmaid, a stay former [corset maker], a machinist [sewing machine operator], and a fur sewer. These were low paying occupations, though the last three seamstress-type jobs may have allowed her to work from home while caring for her children.

Saved by the Ripper?

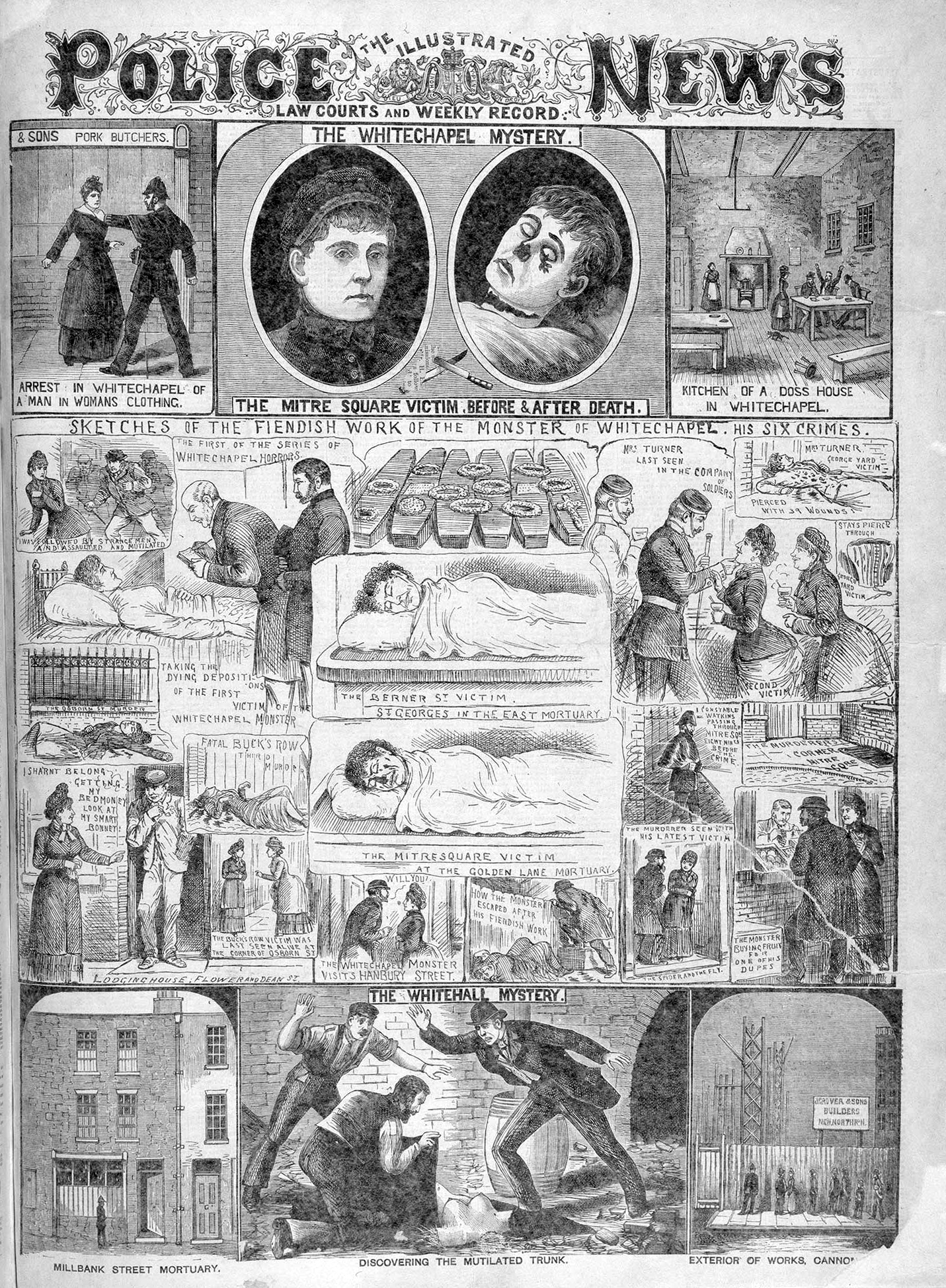

As I read these stories and related them to Sarah’s experiences, a question arose: was Sarah aware of the the widely reported crimes of Jack the Ripper and if so, how did those gruesome articles affect her? Jack’s murderous spree covered the period from August through November 1888 when he attacked and eviscerated five women. Newspapers at the time covered the murders in bold headlines and graphic drawings. There could hardly have been anyone in London’s East End who wasn’t spooked by the specter of a butchering madman stalking prostitutes.

Sources: 1. Hallie Rubenhold, The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper, (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019), p 290. 2. Judith Flanders, “Prostitution,” British Library: Discovering Literature: Romantics & Victorians, https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/prostitution. 3. George Rosen, “Disease, Debility, and Death,” from The Victorian City: Images and Realities, edited by H. J. Dyos and Michael Wolff, (London: Routledge Degan and Paul, Ltd., 1973), 657. 4. Revisiting Dickens, “Prostitution in Victorian England — Presentation Page,” https://revisitingdickens.wordpress.com/prostitution-victorian/

It gives us something to ponder, Jamie. Was the murderer ever uncovered?

Many theories have been posited but to my knowledge none of them have been proven.