I probably owe my fascination with fountain pens to James Wellington McCrie.

My grandfather was an accountant and he kept a stash of dipping pens and spare nibs in his desk drawer. I grew up in his house and frequently rummaged around in his desk. He didn’t mind; he’d passed away nine years before I was born.

I went to the same elementary school as he did. When I attended it was the oldest school in Detroit. The desks still had ink wells. My older sister remembers using them, but by the time I began cursive writing the ballpoint had replaced the dipping pen in the classroom.

Nevertheless, exposure in my youth to the ink wells and to my grandfather’s cache of pens stirred thoughts of using a fountain pen when I was in college and I bought a cheap one with ink cartridges. I didn’t use it long—it leaked like a sieve and made a mess of both my paper and hands.

Years later I got a leather holder with a nice pen and pencil as a gift from co-workers. There was a different feeling to extracting those writing instruments from their pouch than with grabbing a Bic pen from the drawer. Maybe it was similar to the way one feels when putting on a suit and knotting a tie rather than pulling on jeans when going out to dinner: a feeling of anticipation, deliberation, mindfulness, sophistication.

Later still I attended a seminar where one of my classmates had a Montblanc ballpoint pen. It was the first time I felt pen envy; I was determined to have one of my own. I bought a Montblanc knockoff (i.e., fake) pen from a street vendor in New York. Unfortunately it just wasn’t the same—like wearing a tee shirt with a bow tie print to a formal affair—and I didn’t use it long, nor did I ever take it out of the apartment.

I reconnected with fountain pens when my wife and I visited her cousin in Los Angeles a couple of decades back and we were introduced to a friend of hers. Her friend worked as a district sales manager for Montblanc and she enthused about her personal fountain pens. She hooked me up with a deal on a Meisterstück fountain pen, and writing has never been the same. It’s tactile and pleasurable: deliberate, mindful, sophisticated.

Which brings me back to James Wellington McCrie. I’m naming one of my favorite fountain pens for the man who started me on this writing journey.

The pen I have in mind is a Pelikan Souverän M805 Stresemann. The pen’s striped gray barrel was designed after the suits worn by the Weimar Republic’s foreign minister Gustav Stresemann (1879-1929), a contemporary of my grandfather’s.

The design gives it a “buttoned down” look that would have been appreciated by my accountant grandfather. Pictures I have of him show he was a conservative dresser — yes, he wore a real bow tie — and this pen would look great in an accounting office, or any office for that matter. Its black and gray tones are matched with palladium plated clip and rings, and a rhodium plated 18-carat nib. The pen exudes understated sophistication.

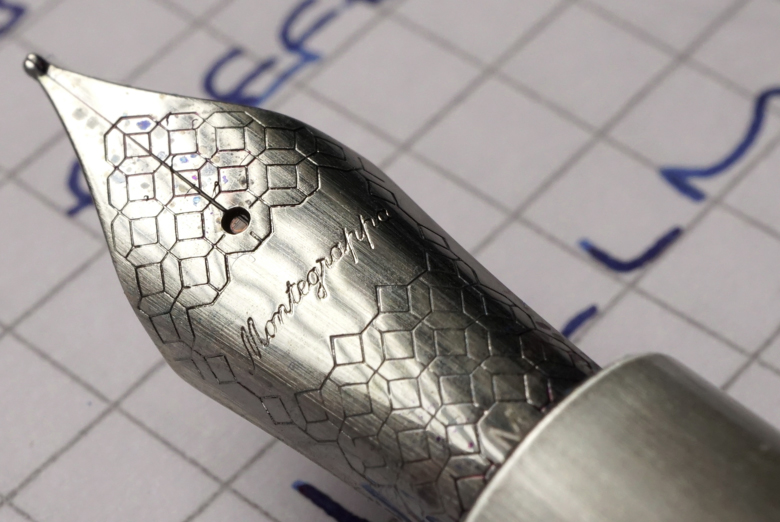

The German-manufactured pen is a piston filler that holds a good amount of ink. When I reflect on my college years’ experience with a leaking cartridge pen, this would be its opposite — it fills easily and cleanly and writes without mishap or misstep. It’s fine-tipped nib would work nicely for an accountant filling in columns of numbers, but I eventually swapped it out for a broad nib more suited to writing lines of flowing text and signatures. That’s one of the strengths of the Pelikan brand, you can interchange the nibs among similar models.

Unfortunately, the pen is not as cheap as the knockoff Montblanc I snagged in New York. However, using the frugality inherited from my Scottish grandfather, I bought it from an on-line retailer in England — Cult Pens — which offers Pelikans at considerable discount over American pricing, especially when the exchange rate is favorable.

Peter Twydle, author of Fountain Pens: A Collector’s Guide, writes, “The one question people ask me more often than any other is, ‘What is the best fountain pen in the world?’ My answer is always Pelikan and, more specifically, the Pelikan M800 and its variants.” I can’t disagree with him. This pen writes beautifully. It fits comfortably in the hand. And with its beak-shaped clip, distinct pelican logo on the finial, and beautifully engraved nib, it is extremely handsome.

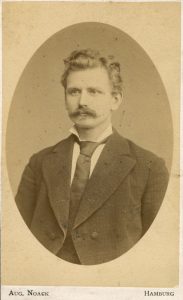

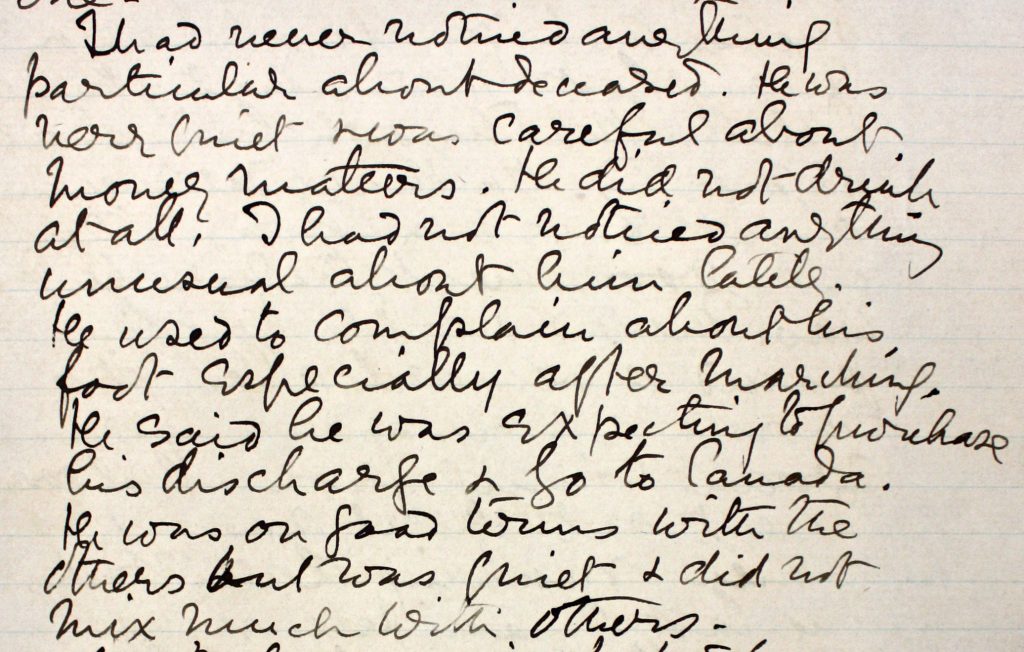

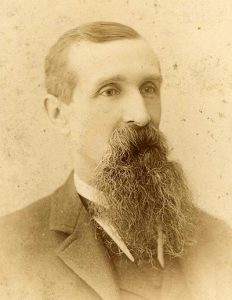

So just who was this James Wellington McCrie I’ve named my pen after? That’s a good question because I never met him, and his wife and daughter didn’t talk about him. His portrait was on the fireplace mantel, but he might as well have been a ghost. So here’s what I’ve found, and I have to say I’ve grown to like him.

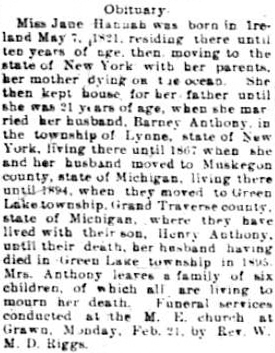

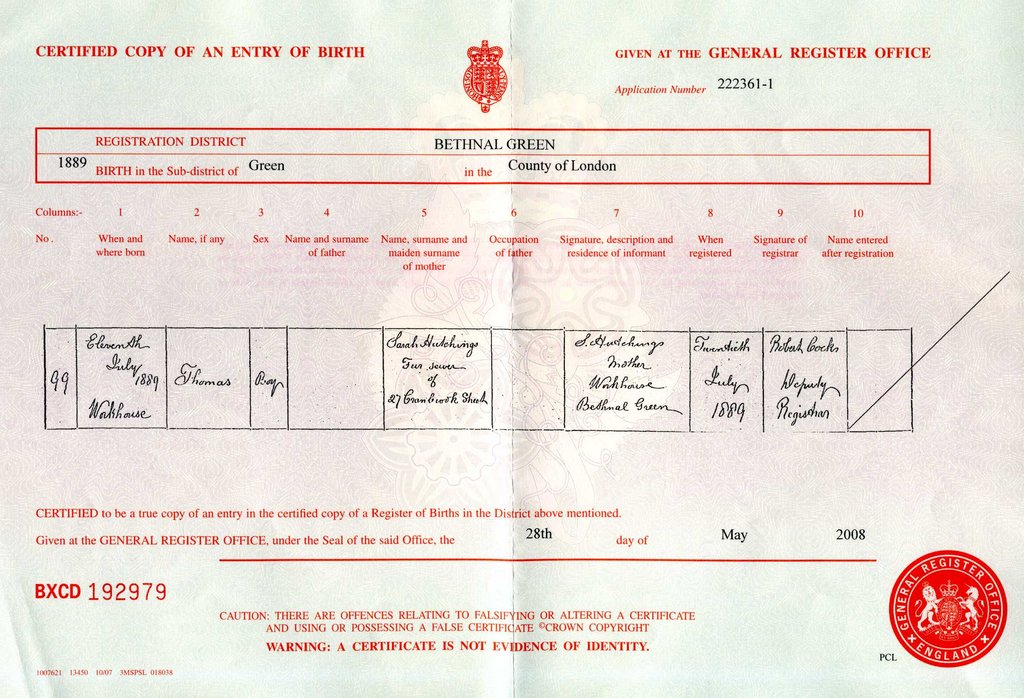

He was born in June of 1878 in Grand Haven, Michigan, to James and Anna (Anthony) McCrie. He was apparently named for his father but given a distinct middle name — a name that doesn’t have precedence on either his father’s or mother’s side.

When James was two years old his father was working as a foreman at the railroad’s grain elevator in Grand Haven along the Grand River. Leading a rather comfortable life, the family lived within a short walk to the river or a twenty-minute walk to Lake Michigan. His father apparently was well regarded, for two years later, in 1882, the family moved to the city of Detroit where his company had just completed a grain elevator in the rail yards on the Detroit River and his father was given the job of weighmaster. James was four years old.

Four years later the family moved to a house on 14th Avenue, where James attended the nearby John Owen Elementary School. His public education continued through the eighth grade; after that he attended the Detroit Business University for between six and twelve months to complete the business curriculum, taking courses in business writing (including penmanship of course), business arithmetic, bookkeeping, commercial law, business correspondence, and business paper (invoices, contracts, leases, mortgages, deeds, etc.).

The education stood by him well as he worked his way up from clerk, assistant bookkeeper, bookkeeper, paymaster, accountant and cost accountant over the course of his career in various businesses around Detroit.

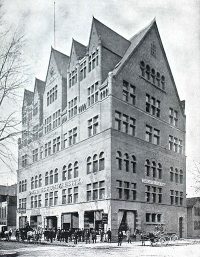

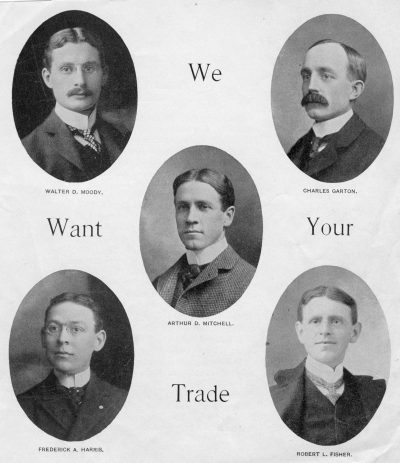

He began at age 17, working as a clerk at Michigan Carbon Works, a stone’s throw from the Detroit River where today Cobo Hall is located. At age 21, in 1899, he was working as an assistant bookkeeper at Wm. H. Elliott, a store selling clothes and dry goods on the corner of Woodward Avenue and Grand River. The handsome 6-story red brick Elliott building still stands on the northwest corner of the intersection.

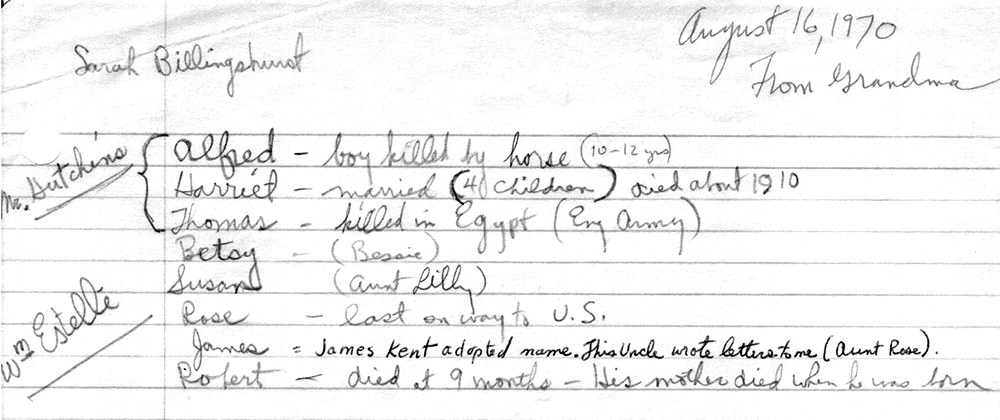

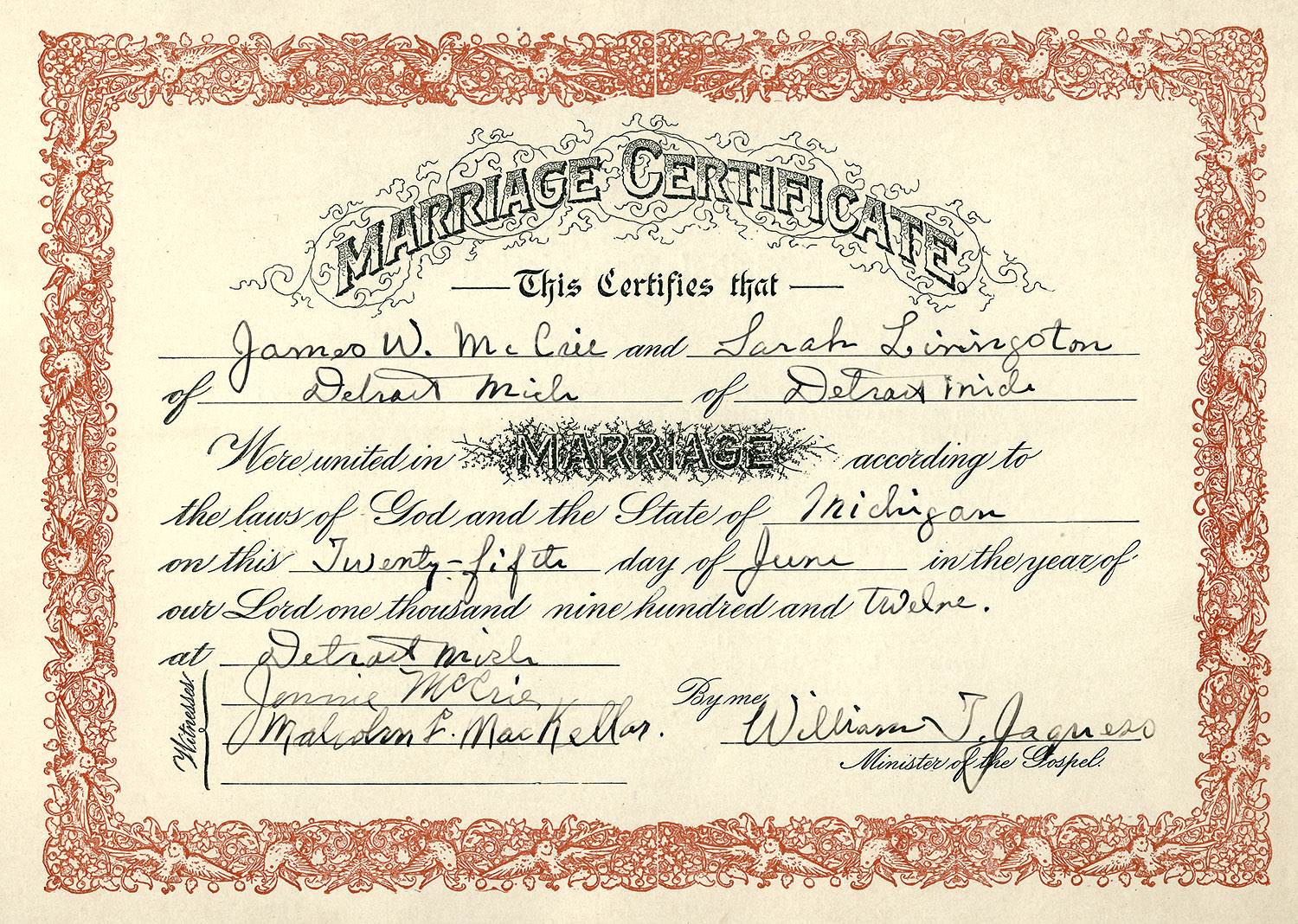

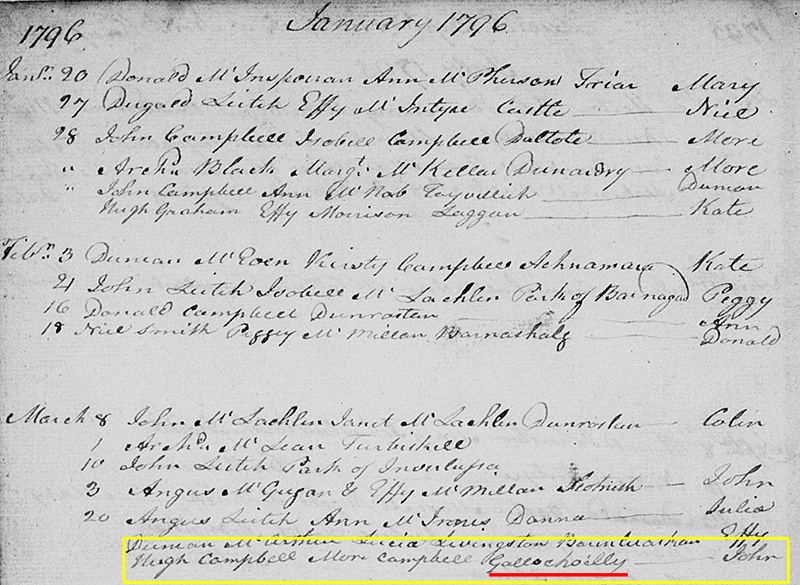

Four years later he was working as a bookkeeper at Crown Hat Manufacturing Company. He worked there for six years, and I believe it was while he was there, in about 1905, he met his future wife, Sarah Livingston, who was working as a stenographer at a millinery (hat) wholesaler a few blocks away in downtown Detroit. The couple put off marriage for seven years while Sarah was living with her elderly mother and young orphaned cousins. She wanted to delay starting her own family until the cousins were grown.

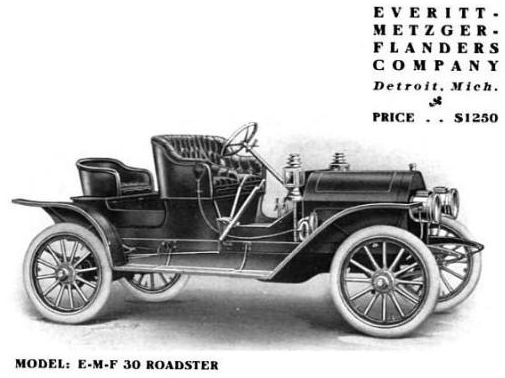

In 1909, at age 31, James was a bookkeeper at Everitt-Metzger-Flanders. The company, more commonly known at E-M-F, was the fourth largest automobile manufacturer at the time, with Henry Ford’s company being the largest. Ford’s small factory, now a museum, was on the neighboring block on Piquette Avenue.

James would have shouldered his way to work in the heart of the fledgling auto industry amidst a stream of factory laborers on the streets, with machinists, engineers, inventors, and automobile tycoons bustling about. From his office he’d hear the thrump of machinery, the grunts of men, the cranking of engines, and the whistles of trains arriving with parts and departing with new cars. It was a time of energy, competition, and excitement in Detroit, centered in the neighborhood where he worked.

In 1910 Studebaker took over E-M-F and expanded the plant into Henry Ford’s factory when Ford moved his operations to Highland Park. (Interestingly, Studebaker ran its cars through Henry Ford’s old office at the front of the building on their way to the rail head.) James McCrie became an accountant with Studebaker that year. When the head of the company started up the Maxwell Car Company three years later, in 1913, James moved with him and became the paymaster at Maxwell.

It was a time of excitement in James’s personal life as well. He married Sarah Livingston in 1912 when he was 34 and she was 36 and in a couple of years they moved into a house on 14th Avenue a block from his mother’s.

They started their family quickly, with son William born in 1914; daughters Margaret and Jean followed in 1915 and 1917 respectively.

With his new family established, James changed jobs again in 1918, becoming a bookkeeper and accountant for a pair of attorneys on the 14th floor of the Ford Building in downtown Detroit, a skyscraper of its day and a building that still stands. He was only there shortly though; the next year, at age 41, he started working for a lithographic company, Calvert Lithographing, on Grand River Avenue. He became a cost accountant for the prosperous and long-established firm; the job was solid, supporting the family through the Great Depression of the 1930s.

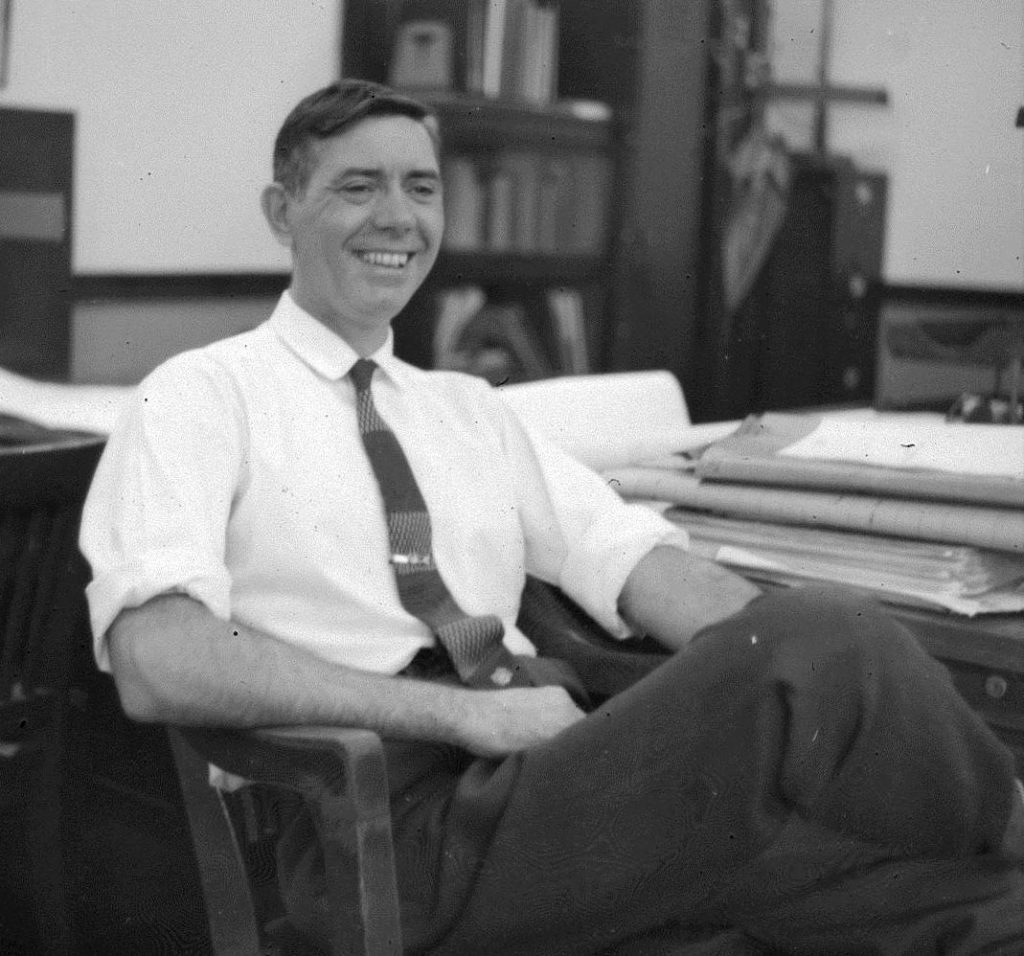

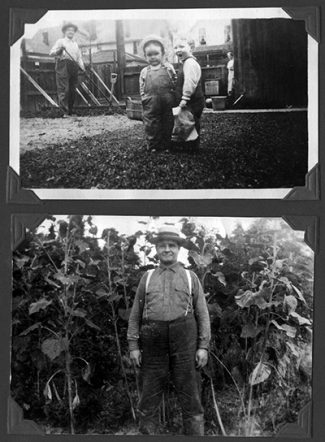

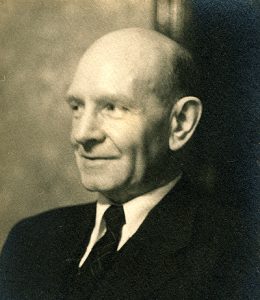

From photographs of James we know he was bald at an early age, overweight, a bit stiff, and almost always wore a tie. He seems to have had a sense of humor, but one he kept in check. Accountants are generally known to be conservative, conscientious, rules-based, and unimaginative in their work, and James looks like he fit the bill, right down to his socks.

Pictures show he worked a flower and vegetable garden in his back yard, and he had a chicken coop as well. He rented out the upper story of his two-story home, a common practice of that day and area. His bank book showed he religiously put money into savings, even during the years of the Depression, so he must have known how to manage his own as well as company funds.

Though he looked self-possessed in all of his photographs, my sister tells the story that he became so exasperated with his headstrong daughter (my mother), he once took her by the heels and hung her down the clothes chute when she misbehaved. He apparently wasn’t as unflappable as photographs suggest. (Clothes chutes were much bigger in those days. I used to sit in it and play astronaut during the early space exploration years.)

By his early 50s James’s love of ice cream and his sedentary job may have contributed to his developing chronic myocarditis and nephritis, which felled him at the age of 62. Bed-ridden in his last months, he died at home on the day his son was married in October of 1940.

I wish I’d had the chance to know him.

I also wish I’d had the foresight to keep at least one of his pens.

Instead, I have to settle for naming one of my favorite pens for him, thinking of him when I pick up the conservatively dressed Pelikan Stresemann. I call it ‘The Wellington’ in his honor. I think it’s an apt name.

Proximity is useful in figuring out family history in the absence of direct evidence such as lineage notes or official records. Relationships are typically established between people who are proximate in space and time. Generations ago one’s social environment would have been largely limited to a day’s travel on horseback or foot. So if a genealogist is trying to deduce or confirm relationships, i.e. build family trees, it’s helpful to establish that the people lived in the same area at the time in question.

Proximity is useful in figuring out family history in the absence of direct evidence such as lineage notes or official records. Relationships are typically established between people who are proximate in space and time. Generations ago one’s social environment would have been largely limited to a day’s travel on horseback or foot. So if a genealogist is trying to deduce or confirm relationships, i.e. build family trees, it’s helpful to establish that the people lived in the same area at the time in question.

Mr. McGuire: I just want to say one word to you. Just one word.

Mr. McGuire: I just want to say one word to you. Just one word.

sacrifice of my own. I’m sure it was his guiding spirit that steered some yokel into backing his pickup truck into the front of my automobile. I could almost hear Barney’s rheumy laugh as the grill on my car caved in and began to look like what I imagined was his gap-toothed grin. Touche, Barney. I’m not likely to forget this little visit into your past. Apparently you still have a few tricks left up the sleeve of that uniform.

sacrifice of my own. I’m sure it was his guiding spirit that steered some yokel into backing his pickup truck into the front of my automobile. I could almost hear Barney’s rheumy laugh as the grill on my car caved in and began to look like what I imagined was his gap-toothed grin. Touche, Barney. I’m not likely to forget this little visit into your past. Apparently you still have a few tricks left up the sleeve of that uniform.

And the people were great: the owner of the cherry store kept her shop open for our late arrival, and a researcher at the public library gave me tips on finding the family in the library’s on-line archives of the Traverse City newspapers.

And the people were great: the owner of the cherry store kept her shop open for our late arrival, and a researcher at the public library gave me tips on finding the family in the library’s on-line archives of the Traverse City newspapers.

The Pelikan I’ve named in his honor is not as quiet as was James, and that’s a shame. The nib has an annoying habit of “singing” when I write in cursive. Beyond the screech, however, the pen is a joy to hold and pleasurably springy to write with, given the nib’s gold content and its massive size — the nib is the size of the last joint on my pinky finger.

The Pelikan I’ve named in his honor is not as quiet as was James, and that’s a shame. The nib has an annoying habit of “singing” when I write in cursive. Beyond the screech, however, the pen is a joy to hold and pleasurably springy to write with, given the nib’s gold content and its massive size — the nib is the size of the last joint on my pinky finger.