“Come on, you Wolverines!”

— General George Custer, rallying the Michigan Cavalry at Gettysburg, 3 July 1863

“As we passed into the field a shell exploded directly in front of us. It took a leg off a man who had dismounted to fight on foot, and I saw him hopping around on his one remaining limb and heard him shriek with pain.”

— Captain James Kidd, Michigan Cavalry, recalling the battle at Williamsport, 6 July 1863

“Dammit! Dammit! Dammit! Dammit!”

After the searing physical pain and shock, the mental desperation kicked in. Looking at the bloody mass of flesh and bone where a whistling shell fragment had severed his leg, he knew his life was forever changed . . . and then the Rebel army captured him.

Jacob A. Heist, my wife’s great-great grandfather, was an eighteen year old farm boy, a volunteer in the 6th Michigan Cavalry Regiment, soldiering on through an extraordinary week of fatigue, fear, excitement, and danger. His brigade had battled J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry on horse and foot around Gettysburg just days ago. He’d slept astride his horse through night marches … watched in awe and dread as the roar, smoke, and iron of cannon fire tore through large swathes of men and horses at Gettysburg … struggled blindly uphill at Monterey Pass against a rain of enemy fire while covered by nothing but the dark of night and six inches of mud. The bright sense of adventure and gallantry was fading quickly as war’s dark realities bore down on his body and mind.

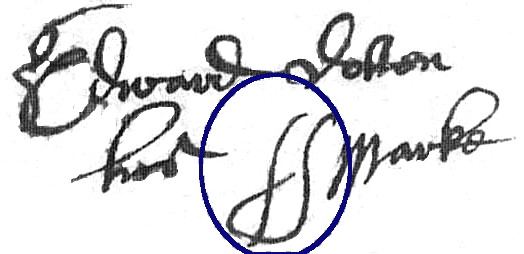

He’d enlisted as a private in September 1862 after hearing a rousing recruitment speech at a war meeting in a schoolhouse in St. Charles Township, possibly the one across the road from his family’s farm in Saginaw County, Michigan. Newly-minted Lieutenant Throop of Owosso handed Jacob the pen to sign up for Company G of the nascent Michigan Sixth Cavalry Regiment. By October, the unit was assembled and mustered into service at Camp Kellogg in Grand Rapids. In December the regiment went by train to Washington, D.C., where they slept the first night under the dome of the Capitol building. From December through February they were stationed on Meridian Hill on the outskirts of Washington, where they could see the President’s House one mile directly to the south. They trained at least six hours a day with their horses, sabers, pistols, and newly issued Spenser repeating rifles. On down days, they walked the capitol’s muddy roads to look at the President’s house, treasury building, Smithsonian building and Robert E. Lee’s former home in Arlington across the Potomac River. It was a time of excitement and anticipation for the young lad from rural Michigan.

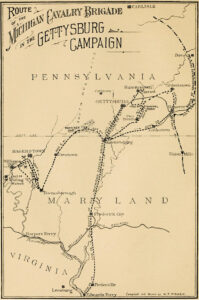

In February 1863 his regiment moved to the grounds around Fairfax Court House in northern Virginia and spread out on picket duty in defense of the Union’s capitol. Over the next four months they made three forays as far south as Frederick, Virginia, and as far west as the Blue Ridge Mountains on reconnaissance missions, but saw very few enemy troops.

The March North

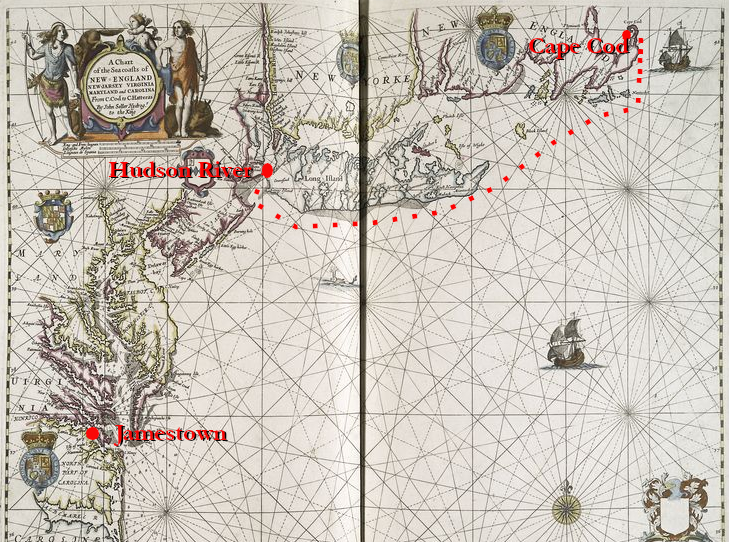

That changed in June 1863 when Confederate General Robert E. Lee moved his Army of Northern Virginia along the western side of the Blue Ridge Mountains into Pennsylvania to take the fight to the north. The Union’s Army of the Potomac headed north in pursuit – along the eastern side of the mountains – to stand between Lee and his presumed destination of Baltimore or Washington.

At first light on Thursday morning, June 25, Jacob’s regiment moved out of their camp at Fairfax, Virginia. After days of hearing the cannons’ booms along the Blue Ridge, Jacob was undoubtedly excited to be moving toward the fight. The Sixth Cavalry Regiment was assigned rear guard to protect the end of the hours-long line of Union troops and supplies heading north. He crossed the Potomac at Edward’s Ferry, near Leesburg, after nightfall, with the strong, rain-swollen, mile-wide river reaching nearly to the top of his horse’s saddle. After straining up the slippery bank on the Maryland shore, his regiment continued through the rain until two a.m., when they bivouacked in the woods near Poolesville. They stayed the next night near Frederick, Maryland, and the night of the 27th near Emmitsburg, Maryland, close to the Pennsylvania border.

On Sunday morning, June 28, the Fifth and Sixth Michigan Cavalry Regiments were sent along the Emmitsburg Pike on a scouting mission to the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. As it happened, they were the first Union troops to enter the town.

The townspeople greeted the regiments in their Sunday best. It was a proud day for Jacob when he saw the turnout for the troops. Captain Kidd of the Sixth Regiment writes, “The church bells rang out a joyous peal, and dense masses of beaming faces filled the streets as the narrow column of fours threaded its way through their midst. Lines of men stood on either side, with pails of water or apple-butter, and passed a sandwich to each soldier as he passed. At intervals of a few feet were bevies of women and girls, who handed up bouquets and wreaths of flowers. By the time the center of the town was reached, every man had a bunch of flowers in his hand, or a wreath around his neck.”

Within a couple of days, however, the glory of war gave way to the gore.

First Combat

The Sixth Cavalry spent all day on Monday, the 29th of June scouting to the south and east of Gettysburg, and continued into the night, the troops dozing by turns in their saddles. They knew Lee’s army was nearby, as were J.E.B. Stuart’s cavaliers. They were ten miles southeast of Gettysburg on the morning of the 30th when a local citizen told them of the Confederate cavalry’s presence near Hanover, a few miles to the northeast. The bugler played “To Horse” and the troop mounted and set off to face their first combat of the war.

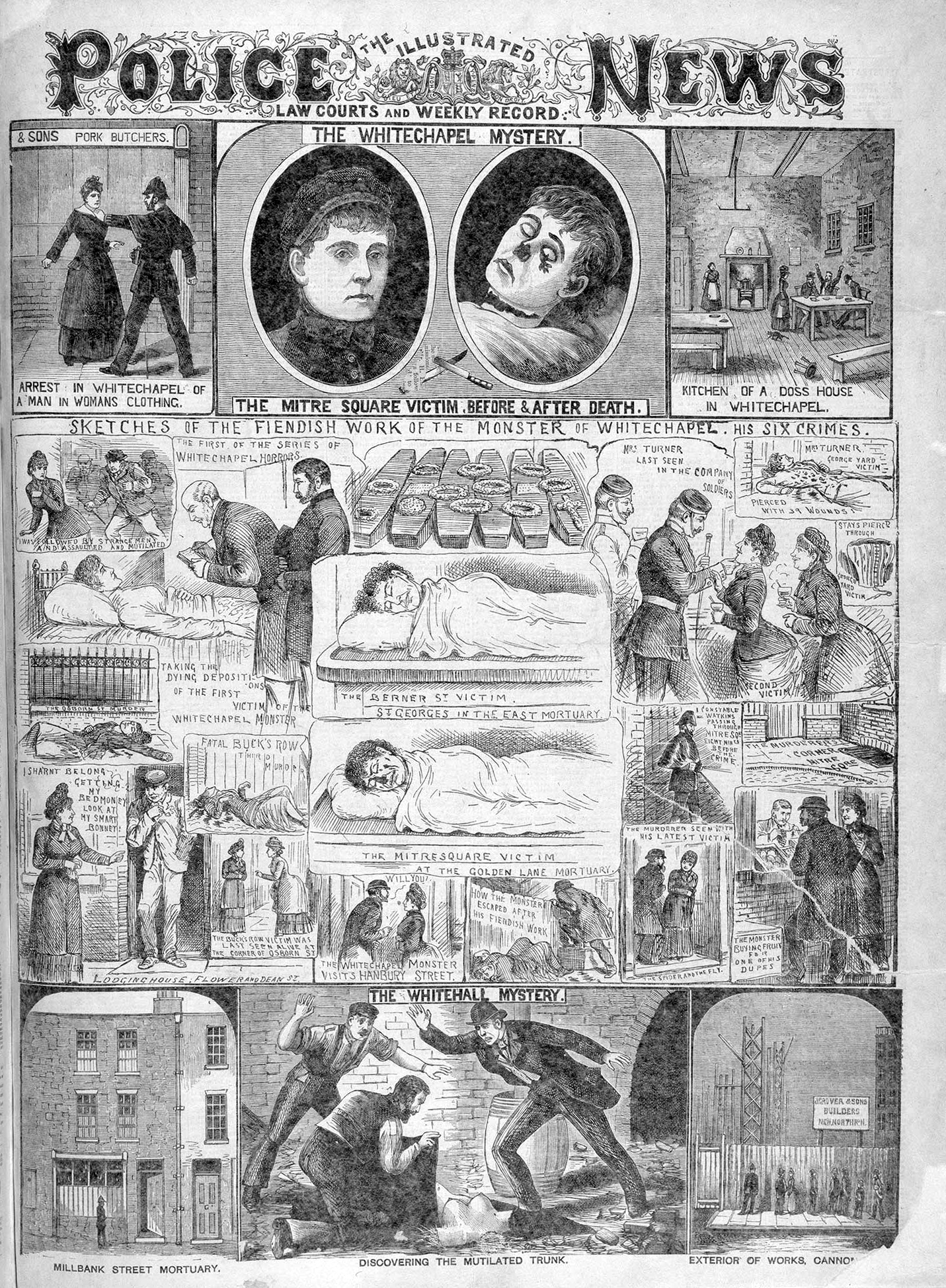

Just short of Hanover the regiment turned into a wheat field and came upon Confederate cavalry, whose artillery opened up on the Sixth Regiment, wounding several men and horses. The regiment withdrew to join its parent division in Hanover, where a battle ensued within and south of the town. It was at Hanover that Jacob and his fellow soldiers first saw their new brigade commander, the flamboyant George Custer, who’d just been promoted to General at the age of 23 and assigned command of the First, Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh Michigan Cavalry regiments as well as Lieutenant Pennington’s horse artillery battery. Fighting that day forced the Confederate cavalry to detour to the northeast and delayed Stuart’s reunion with Lee’s army to the west by a couple of critical days.

The mass of the Union and Confederate armies met in Gettysburg on Wednesday, July 1st, beginning three days of unprecedented deadly combat. Jacob’s regiment remained east of Gettysburg on the 1st, traveling north to Abbottstown and then west towards Gettysburg via Hunterstown on the 2nd, where they met Confederate cavalry blocking the road to Gettysburg. A two-hour battle ensued. Jacob and his fellow troopers dismounted, entered the woods at the side of the road, and fired upon the charging Confederate cavaliers, driving them back. The battle was a stalemate, with no clear victor or loser. At the end of the day, the Sixth headed south to bivouac near the hamlet of Two Taverns southeast of Gettysburg.

Gettysburg Battle

On Friday, July 3rd, the Union cavalry – including the Sixth Regiment in Custer’s brigade – was ordered to protect the Union’s far right flank from attack by J.E.B. Stuart, who in turn had intentions of skirting their flank and attacking the Union’s rear from the east while Lee attacked its front from the west. The Union cavalry intercepted Stuart’s path about three miles east of Gettysburg on fields surrounding John Rummel’s farm, setting up a cavalry battle among seven to eight thousand troops and their supporting artillery. The Sixth Regiment was positioned toward the rear to guard the intersection of Hanover and Low Dutch roads and to repel any Confederate attempt to capture Pennington’s battery.

The Confederate field guns opened on Custer’s brigade around noon, raining iron on Custer’s troops and horses. Pennington returned fire, knocking out two of the rebel field guns. Confederate forces advanced as far as the farm and paused. Around one in the afternoon a furious roar shook the earth and sent clouds of smoke rolling over the fields from Gettysburg three miles west, where Lee’s army began bombarding union lines with a 150 cannon fusillade that could be heard 140 miles away. He was trying to soften up the main Union line in advance of an infantry charge.

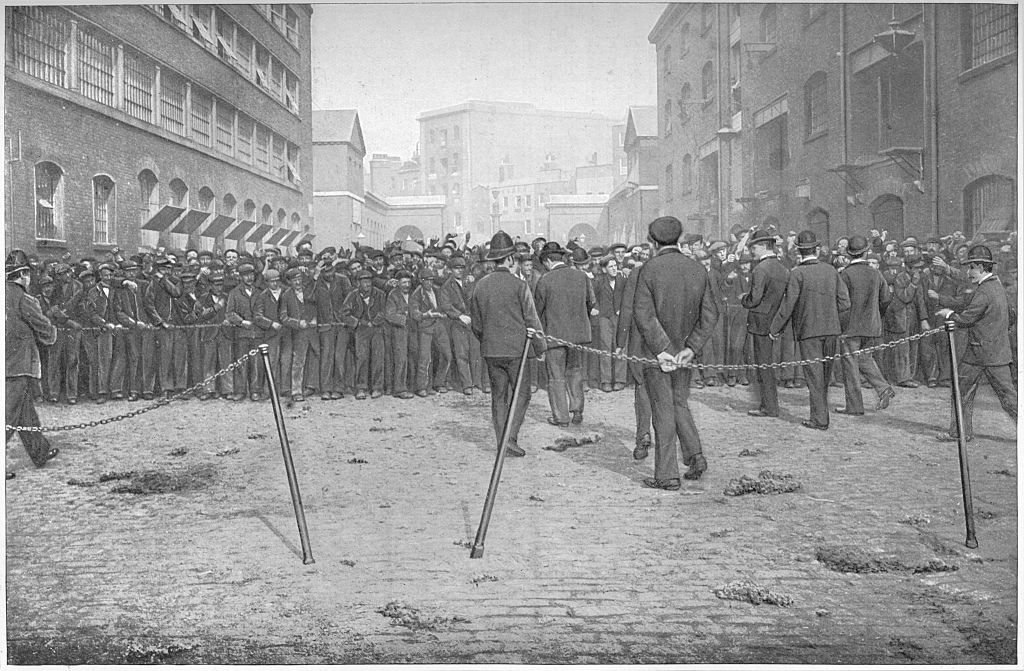

Shortly thereafter the battle between the cavalries in the east began in earnest, with roaring cannons belching shrieking shells, and yelling troops falling upon each other in bloody charges, hasty retreats, and fierce countercharges. Horses were shot out from under cavaliers. Formations of grey-clad men came out of the woods beyond the farm. Charges were made on horse with sabers and pistols; dismounted troops used rifles as they advanced. The combatant forces ebbed and flowed like a red tide, channeled by farm fences, woods, and creeks. One side gained ascendency, only to lose it with an opposing counter-assault. Captain Kidd of the Sixth Cavalry recalled one of the Union assaults:

“Just then, a column of mounted [Union] men was seen advancing from the right and rear of the union line. Squadron succeeded squadron until an entire regiment [roughly 1200 men] came into view, with sabers gleaming and colors gaily fluttering in the breeze. It was the Seventh Michigan, commanded by Colonel Mann. … As the regiment moved forward, and cleared the battery, Custer drew his saber, placed himself in front and shouted: “Come on, you Wolverines!” The Seventh dashed into the open field and rode straight at the [Confederate] dismounted line which, staggered by the appearance of this new foe, broke to the rear and ran for its reserves.”

The attacks and close-contact fighting lasted about three hours, with a few skirmishes continuing until nightfall. Casualties totaled about 700 between both sides, or roughly one out of every ten soldiers. However, the Union successfully stopped the Confederate cavalry from flanking its right side. The result was that the Union artillery and infantry back in Gettysburg were able to concentrate on Lee’s assault from the west, with disastrous consequences for the Confederacy.

The attacks and close-contact fighting lasted about three hours, with a few skirmishes continuing until nightfall. Casualties totaled about 700 between both sides, or roughly one out of every ten soldiers. However, the Union successfully stopped the Confederate cavalry from flanking its right side. The result was that the Union artillery and infantry back in Gettysburg were able to concentrate on Lee’s assault from the west, with disastrous consequences for the Confederacy.

After the failed Confederate assault at Gettysburg, the Confederate army began a retreat back to Virginia. Jacob Heist was among the Union soldiers in pursuit.

Jacob’s Sacrifice

The rain came down steadily and hard for the next couple of days as the Union Cavalry began its pursuit of Lee’s retreating army on Saturday, July 4th. The men were wet and exhausted from days on end of marching, reconnaissance, lost sleep, and combat. Nevertheless, the Michigan men were proud to have matched the far more experienced Confederate cavalry in their first encounters of war and they were jelling as a force.

All day long they “plodded and plashed along the muddy roads towards the passes in the Catoctin and South mountains.” At night they caught up to a Confederate wagon train in the Blue Ridge Mountains of southern Pennsylvania at Monterey Pass. The Michigan Fifth and Sixth Cavalry were the lead troops in climbing the road to the pass, where they were met by artillery and infantry fire in the dark of a muddy, rain soaked night. A confused battle ensued, in which the soldiers sometimes could only tell where the enemy was by the flashes of their guns and cannon. Nevertheless, Custer’s troops were able to rout the Rebels for a while, burning and plundering their wagons until Confederate reserves arrived. At morning, the Sixth withdrew and headed south toward the Potomac River, which Lee’s army would have to cross on its way back to Virginia.

The 5th of July Jacob’s regiment rode down along the spine of the Blue Ridge to Boonsboro, Maryland, southeast of Hagerstown, engaging in occasional skirmishes with rebel troops along the way.

On the afternoon of Monday, July 6, 1863, the Fifth and Sixth Regiments arrived in Hagerstown, and started south down the pike to Williamsport, where General Lee’s reserve wagon trains were gathered at the Potomac shore, unable to cross due to the rain-swollen river. To the Sixth’s front were the forces of the Confederate General Imboden; to their rear was the rest of Lee’s Army. They began to fear they were going to get trapped on the road, but pressed on toward Williamsport, five miles south.

On a bluff about a mile from Williamsport they were met by General Imboden’s artillery which poured shells in on the position where the brigade was trying to form. The Sixth was sent into a field on the right of the road.

On a bluff about a mile from Williamsport they were met by General Imboden’s artillery which poured shells in on the position where the brigade was trying to form. The Sixth was sent into a field on the right of the road.

Continuing with Captain Kidd’s narrative:

“As we passed into the field a shell exploded directly in front of us. It took a leg off a man in troop H which preceded us and had dismounted to fight on foot, and I saw him hopping around on his one remaining limb and heard him shriek with pain. A fragment of the same shell took a piece off the rim of Lieutenant E. L. Craw’s hat. He was riding at my side. I believe it was the same shell that killed Jewett…a fragment of one of these shells struck him in the throat and killed him instantly.”

It was here that Jacob A. Heist was hit by a shell that “shot away his left leg below the knee.” It is quite likely that the soldier Captain Kidd saw hopping in pain on the battlefield was Jacob. At any rate, Jacob’s combat days ended at Williamsport, Maryland on July 6th when he sacrificed a leg to the cause of the American union on a Civil War battlefield. Adding insult to injury, he was captured by Confederate forces and his initial amputation was performed by a Confederate surgeon.

Pre-Civil War Years

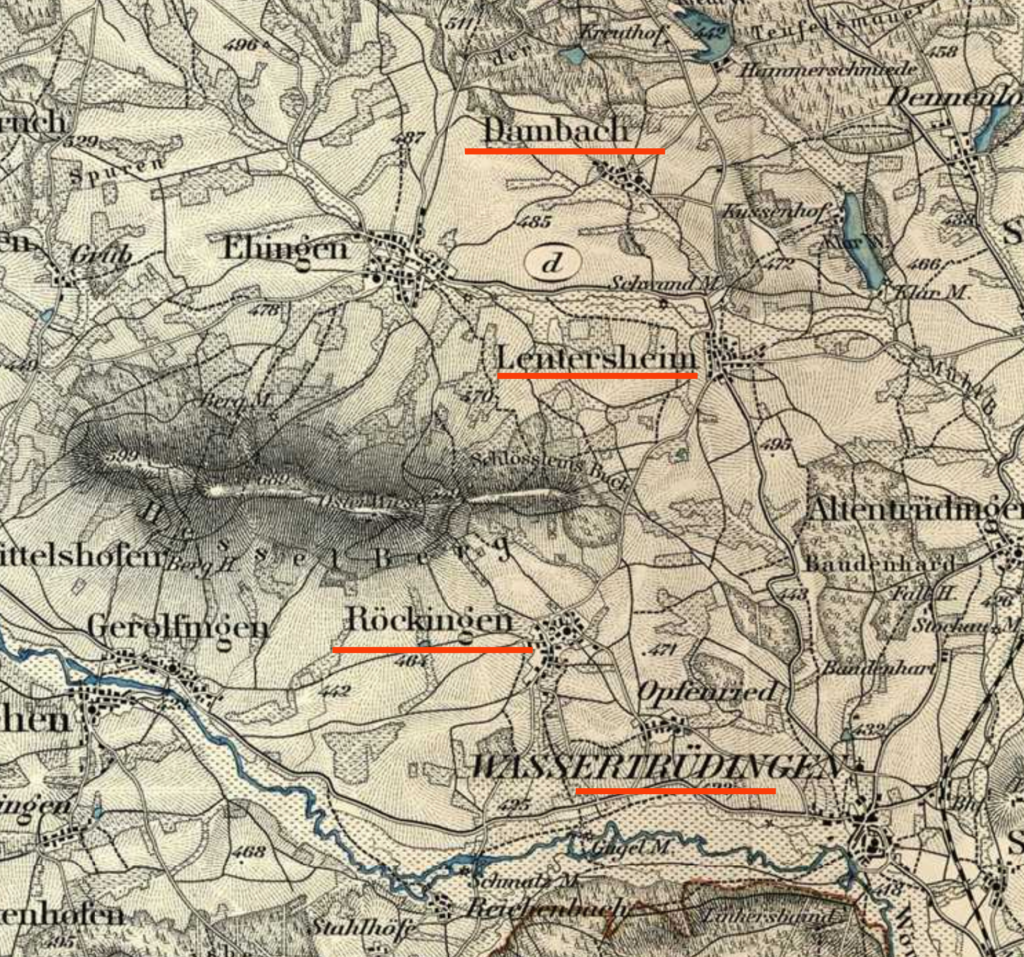

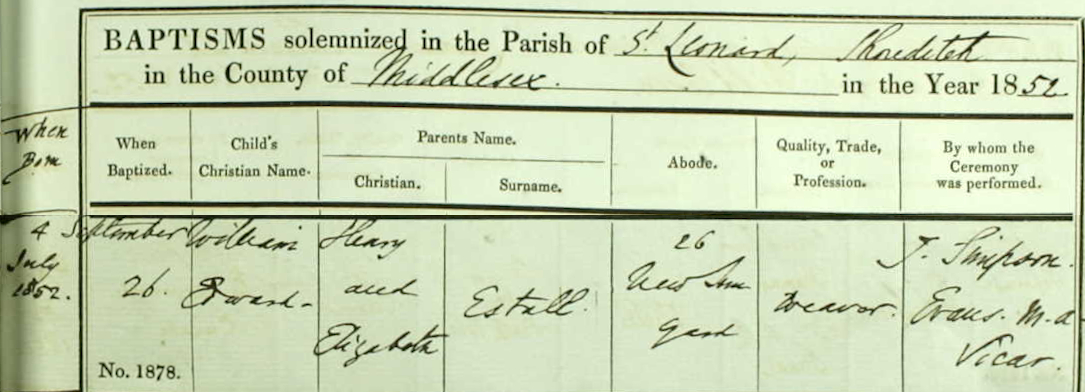

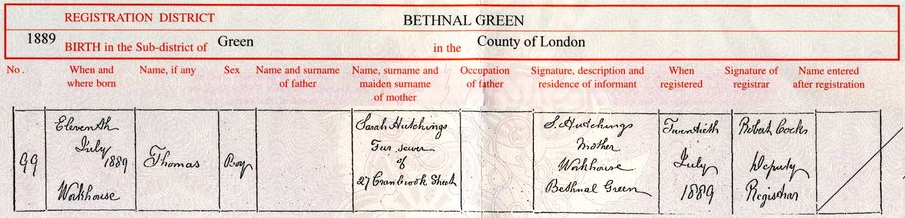

Jacob was born in Buffalo, New York, near the corner of Genesee and Mortimer streets, in December 1844, the second child and first son of a German immigrant family. His father, at age 23, was working as a clerk at a hardware store on Main Street and living in his own father’s home. Jacob’s grandfather was working as a laborer. (For more on Jacob’s German ancestral lineage, see the upcoming post: The Haist Family of Germany.)

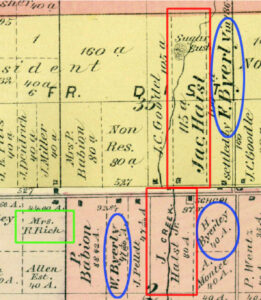

In 1861 Jacob’s father moved the family to St. Charles Township in Saginaw County, near the town of Chesaning. Jacob’s family and his mother’s family (her maiden name was Christina Byerly) settled on adjoining farms. Jacob, sixteen years old, would have been working the 115-acre Heist farm with his dad, learning about horses and farm equipment, and perhaps cooling his feet during the summer in Bear Creek which ran through the farm. (See map a few paragraphs below.)

When the War of 1861 started, he was a cavalry recruiter’s dream: a lad in the prime of life, familiar with horses, patriotic (no recruitment bonuses were offered, or needed, at the time), and eager for adventure. Standing 5 feet, 10 inches, with a dark complexion, dark hair and blue eyes, his departure for war in 1862 may have broken a few hearts in St. Charles, and most surely that of his mother’s.

Post Civil War Years

The war was unkind to Jacob. After the leg wound received at Williamsport in July 1863 his left leg was amputated six inches below the knee and he was fitted with an artificial limb. He spent nine months at Union military hospitals in Annapolis, Maryland, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and was medically discharged in May 1864 with a disability pension.

He returned to his father’s farm in St. Charles where he worked as a day laborer, but his employment opportunities were probably restricted by the loss of his leg and his limited education (he was able to read but unable to write). Fortunately the pension appears to have supported him financially, running parallel with or somewhat above the average wage earned at the time.

Although his artificial limb rubbed annoyingly against the stump of his leg, his limp was apparently not off-putting to others, as Jacob had no lack of wives or children in life.

He married Ellen Rourke, a 17-year-old farm girl from an Irish Catholic family in nearby Rush Township when he was 24 years old. They raised three daughters, including the youngest, Mary Louise Heist (my wife’s father’s grandmother). Unfortunately the marriage lasted only seven years, as Ellen died at the age of 24 in 1876.

By 1877 Jacob owned 80 acres across the road from his father’s farm northeast of Chesaning. Neighboring farms were owned by the families of his mother, Christine (née Byerly) Haist.

In 1878, at age 33, he married Mary Rich, the 27-year-old daughter of an English-born farmer living four farms down the road. Together they raised Jacob’s previous three children and five of their own.

In 1880, at the height of his productive years, the 35-year-old Jacob had two horses, was raising 13 head of cattle and 15 chickens, and producing 500 bushels of corn, 100 of oats, 40 of wheat, 150 of potatoes, and 25 cords of wood on his farm, undoubtedly with the assistance of his four unmarried brothers.

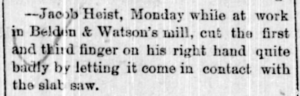

By 1888 he was living four miles away in the small town of Chesaning, Michigan, where he worked at a sawmill. An article in the Chesaning newspaper reported an accident Jacob had while on the job: he cut the first and third fingers on his right hand “quite badly” when he let his hand come in contact with the slat saw. [One can only imagine him limping around town with his left leg a stump and his right hand heavily bandaged — Jacob could have been a poster boy for a modern-day Job.]

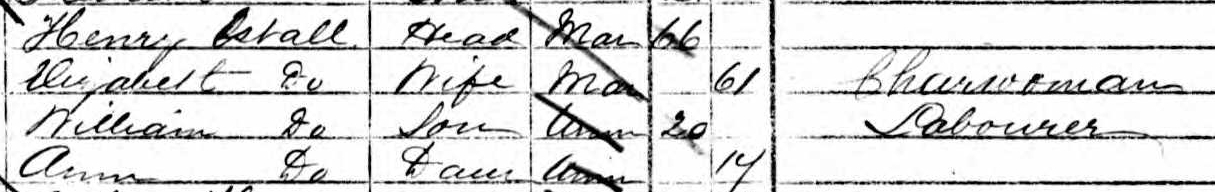

In the early 1890s the middle-aged Jacob moved to nearby Owosso, Michigan. His prime years behind him, physical ailments – some of them related to his military service – began to incapacitate him. In an affidavit dated December 1895, two local witnesses observed that “he is in very poor health from his wounded leg and suffers at times from it so he is not able to leave the house and [is] under the care of his wife and sun [sic] who take care of him and wate [sic] on him.” Unfortunately, that son, William, died suddenly of unknown causes in 1899 at 19 years of age.

The 1900 census reported that Jacob worked as a common laborer, while living in a rented house with his wife and three teenage children. It may have been difficult at times to sort out who were the adolescents and who was the adult in the household, given that in 1908 Jacob was arrested for disturbing the peace, and earlier that year he was also involved in a shooting . . . of a rooster. According to the Owosso Times newspaper of 27 March 1908:

“Fred and Jake Heist, of Rush [Township], paid Frank Niver $10 for a rooster Monday. They traded a watch for a gun here [in Oakley, north of Owosso] Saturday and started for Chesaning. When passing Frank’s place they thought to try the new gun and took aim at a fine large Plymouth Rock rooster. Asa Niver was a witness to the shooting and reported forthwith to Frank. They offered Frank $2.00 to settle and seemed quite indignant because he refused their offer as they said it was a big price for one chicken. Both are men of mature age, one a veteran of the civil war.”

In 1910 the census reported he was an empty nest pensioner living with his wife Mary. In 1915 Mary died from kidney disease, leaving him a widower for the second time. He moved in with his sister Caroline, a widow living on Owosso’s Main Street.

Jacob was nothing if not a survivor. Despite his age and increasing debility, he married once again, this time in 1921 at age 76 to Louisa Braun, a 53-year-old German divorcee working as a “varnish rubber” at a furniture factory. He moved into her house on Adams Street, and she became his caretaker for the balance of his life.

By 1922, a doctor reported that “on account of tenderness and soreness of [his] leg stump” he was unable to wear his artificial leg much of the time, and because of rheumatism in his shoulders and legs he was unable to use crutches. He had severe deafness in both ears, only able to hear very loud conversation six inches away. He was prone to falling. Because of these conditions, he required “regular aid and attendance … in dressing and undressing and in attending to the calls of nature” and could not go out alone.

16 May 1922

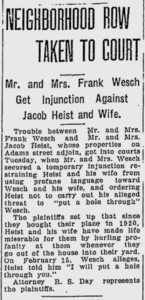

“He was a nasty old creature … well, that’s what my dad always said.” That was the recollection of an elderly John Bartlett in 2005, when he recounted the story of Jacob Heist, his great-grandfather. John’s recollection is borne out in another newspaper article, this one from 1922, reporting that Jacob’s next door neighbors complained that Jacob and his wife made life miserable by hurling profanity at them and threatening to “put a hole through you.”

One surmises some crotchetiness might be expected of a war veteran who was in chronic pain, was twice widowed, was losing many of his faculties, and relied heavily on the assistance of others. Wolverines in nature, after all, are not known for their friendly personalities . . . nor, apparently, was this human one.

Jacob passed away from a cerebral hemorrhage in 1930 at age 85 after a stroke two years earlier had left him paralyzed. His body was buried in Owosso’s Oak Hill Cemetery beneath a War Veteran’s headstone. He left behind 19 grandchildren and 19 great-grandchildren, a remarkable testament to his life force.

Jacob passed away from a cerebral hemorrhage in 1930 at age 85 after a stroke two years earlier had left him paralyzed. His body was buried in Owosso’s Oak Hill Cemetery beneath a War Veteran’s headstone. He left behind 19 grandchildren and 19 great-grandchildren, a remarkable testament to his life force.

His was but a small part in the grand saga of the American Civil War, but his story provides a poignant vignette of the war’s impact on an individual, his family, and his community.

To the end, Jacob Heist was a Wolverine.

Sources for the Jacob A. Heist story include:

- Soldier’s Certificate No. 36338: Jacob A. Heist, Federal Military Pension Application – Civil War and Later Complete File, (Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives), 62. (Army of the United States Certificate of Disability for Discharge, May 21, 1864.)

- J. H. Kidd, Personal Recollections of a Cavalryman with Custer’s Michigan Cavalry Brigade in the Civil War, (Ionia, Michigan: Sentinel Printing Company, 1908), 40.

- “Sixth Michigan Cavalry: Muster-Out Rolls, Cos. F-M,” Seeking Michigan, accessed October 21, 2013, http://seekingmichigan.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p4006coll15/id/41816/rec/16.

- “Sixth Michigan Cavalry: List of Officers and Men,” Seeking Michigan, accessed October 21, 2013, http://seekingmichigan.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p4006coll15/id/33324/rec/9, documents 15 and 16.

- Edward G. Longacre, Custer and His Wolverines: The Michigan Cavalry Brigade, 1861-1865, (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1993), 106.

- “East Cavalry Field: July 3, 1863,” Echoes of Gettysburg, accessed October 21, 2013, http://theechoesofgettysburg.com/id44.html

- Edward G. Longacre, The Cavalry at Gettysburg: A Tactical Study of Mounted Operations During Civil War’s Pivotal Campaign, 9 June-14 July 1863, (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1993), 225.

- “Michigan County Histories and Atlases: Atlas of Saginaw Co., Michigan / from recent and actual surveys and records under the superintendence of F. W. Beers, 1877” University of Michigan.

- U.S. Federal Censuses for Erie County, New York; St. Charles Township, Michigan; and Owosso, Michigan.

- “Local News,” Owosso Times, Owosso, Michigan, August 14, 1908, p5, col 1.

- “Oakley,” Owosso Times, Owosso, Michigan, March 27, 1908, p8, col 1.

- A July 7, 2005, recorded conversation among John Bartlett, Jamie Schutze, Cherie Schutze, Emily Brown, and Bill Brown in John Bartlett’s residence in Surprise, Arizona.

- “Pvt Jacob A Heist,” Find A Grave, accessed October 21, 2013, http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=80754213. Headstone image is from this site.

- “Michigan Online Historical Newspapers: Shiawassee – Owosso: Owosso Argus-Press, 1917-1972,” Google News Archive, accessed October 21, 2013. Issue of July 14, 1930, page 2.